Skin Storm

By Matt Connolly

Magic Mike

Dir. Steven Soderbergh, U.S., Warner Brothers

The announcement of Magic Mike—starring Channing Tatum in a fictionalized account of his own days as an exotic dancer in a Tampa strip club—drove online commentators to lick their collective lips, albeit with salivating tongue partly in cheek. Casting notices only upped the half-ironic, half-giggly expectation for the prospect of a hunk-filled Hollywood flesh-fest. Not only Tatum, but Matt Bomer! Alex Pettyfer! Joe Manganiello! Matthew McConaughey, for chrissakes! Many seemed to anticipate the film with the same self-aware giddiness one would have on, well, a trip to Chippendales. So, when Magic Mike finally began working its way through the pre-release screening circuit, the fact that it had something resembling substance seemed to come as a shock. Though some had tempered their expectations for camp with the knowledge that shape-shifter auteur Steven Soderbergh would be at the helm, others responded to Magic Mike’s blend of strip-tastic gyrations and commentary on the connections between sex and commerce with semi-incredulous surprise. We really can have our beefcake and recognize its commodified status, too!

It’s the kind of buzz that any distributor of a low-budget, character-driven drama released in the middle of summer would dream of . . . or, more to the point, works to cultivate via marketing and publicity. Warner Brothers has been incredibly canny in positioning the film as a naughty romp, and allowing critics and pundits to uncover the beating heart underneath the well-defined pectorals. Ironically, though, emphasizing the “surprising” depth or warmth (or whatever) in Magic Mike downplays what’s most intriguing about the film. You may intend—or claim—to come for the stripteases and stay for the interpersonal struggles, but Magic Mike only truly takes off when focusing on the glistening skin and ritualized bumps and grinds of its muscled protagonists. More than just parading his dreamboat cast before a grateful viewership, Soderbergh locates both the overripe humor and transfixing athletic grace in their routines, his fascinatingly ambivalent camera refusing to tip the scale in favor of either. It’s a complexity that the fully-clothed sequences in Magic Mike could use more of.

Tatum’s Magic Mike acts as entrée into the world of mid-level male stripping for both the viewer and nineteen-year-old Adam (Pettyfer), whom Mike meets while on a construction site—one of many odd jobs Mike works to save enough money to begin a custom-made furniture business of his own. Perhaps seeing a bit of himself in the rudderless Adam, Mike takes him under his wing. He brings Adam to Xquisite, the club where he strips, and convinces its owner/emcee, Dallas (McConaughey), to give him some menial tasks. Adam reacts queasily upon first learning what Mike does for a living, but his uncertainty quickly fades when Mike convinces him to step out on stage after aging dancer Tarzan (Kevin Nash) becomes too inebriated to perform. After a tentative, artless striptease, Adam comes alive when he leaps off stage and begins to make out with a front-row customer. The torrent of dollar bills and female attention convinces him to join the crew, and deepens an already budding friendship with Mike.

Why does Mike himself strip? Besides the aforementioned dreams of entrepreneurship, Magic Mike alludes to his beginnings in the business, with Dallas waxing nostalgic about finding Mike dancing on the street corner and taking him in. Mostly, though, the film illuminates the job’s appeal simply by observing Mike onstage. Tatum has a liquid physicality when he dances, his legs flexing and stretching in rubber band-like fashion before suddenly snapping to attention at a moment’s notice. The verve and spry wit of Mike’s moves rub up intriguingly against the parodies of masculine virility he embodies in his various routines (sailor, solider). This friction between Mike’s nuances of bodily expression and the stock, sexualized roles into which they are poured separates him from his fellow performers, all of whom fit their various stage personas with comfortable anonymity. Soderbergh lets these dissonances play out on screen with minimal editorializing from his camera. He films the men’s routines in a manner neither hyperactively fetishized nor coldly detached, with camera angles and editing patterns that highlight both the corporeal effort put forth by the dancers and the inherent inanity of the fantasies they enact. At its best, Magic Mike offers a vision of erotic labor that eschews judgment without forestalling critique.

Too bad that Reid Carolin’s screenplay isn’t nearly as compelling, putting forth a familiar story of corrupting glamour and the possibility of second chances. Bringing Adam back home after a night of carousing with some very friendly female customers, Mike meets Brooke (Cody Horn), Adam’s overworked sister who views Adam’s newfound profession with suspicion. Mike inevitably begins to fall for Brooke, who can see Mike’s decency but resents the irresponsibility and indulgence that life as a stripper engenders in her brother. In other words, Brooke is but another link in a long, regrettable chain of airless female characters whose humorless nagging both gets in the way of overgrown boys having fun and ultimately represents the promise of domestic bliss. Horn tries to give this dimensionless mother-hen role some sensuous spark, but there’s simply too much deadweight holding her down. Mike and Adam’s friendship, too, undergoes a similar descent into cliché, with Mike’s increasing professional ambivalence corresponding with Adam’s embrace of the club’s decadence. Soderbergh isn’t entirely free from blame here. Outside the club scenes, his visuals run the gamut from the subtly effective (note the way he’ll slice individuals’ heads out of the frame for just a few seconds, leaving us to contemplate a torso or waist) to the hackneyed, as when he incessantly graphic-matches Adam and Mike as they engage in separate acts of substance-fueled sex. If Magic Mike’s stripping sequences have the lively snap of ambiguity, much of the film’s more plot-driven sections run on overused character types and stale moral calculus.

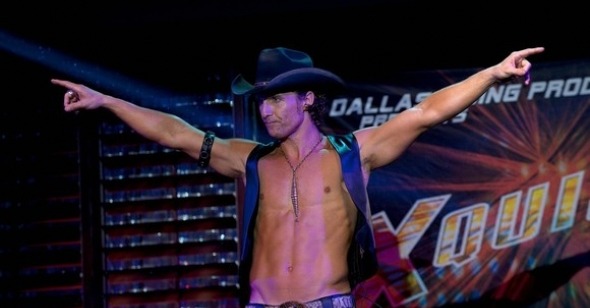

The glorious exception to this rule is McConaughey’s Dallas, a flat-out fantastic comic creation and the film’s debauched soul. His skin grown drawn and ever so slightly leathery with age, McConaughey struts through Magic Mike with oily serenity. He’s at once utterly debased and oddly guileless, a man who has so completely bought into the plastic erotic visions he peddles that it’s difficult to know when the bawdy onstage guise ends and something resembling a “real” personality starts. There’s no better image in Magic Mike than an extended close-up of Dallas, donning Uncle Sam regalia, as he introduces the dancers for a military-style number commemorating July fourth. Before he says a word, Soderbergh frames him dead-center, staring out into the audience with a look both intense and curiously blank. Does he get the absurdity of the act’s swirl of patriotic kitsch and flexing beefcake? Either way, the film slyly hints, it doesn’t matter. He becomes Magic Mike’s most potent embodiment of the pleasures and perils of turning one’s sexuality into a persona and a product—indeed, how thin a line separates the two.