Michael Koresky

Cinema is always about duration, from the quickest cut to the longest, most open-ended camera rove. How much a filmmaker can contain in one passage is the essence of the medium, regardless of matters of length.

The disconnect between the liberated shooting and editing style and the social entrapment actually experienced by its characters gives The Florida Project its indeterminate feel and ungainly shape.

Aronofsky piles on incidents (rather than plot), bodies (rather than characters), until what once had the potential to be a pastoral paradise has become a writhing, grasping, cluttered Bosch-like abyss.

Self-consciously spare and reaching for a grandeur possibly too far beyond its frame, A Ghost Story is nevertheless a film of mesmerizing visual ideas and conceptual integrity.

As film critics, we have been unclear what to do with our despondency, other than one clear thing: direct our outrage away from suffocating social media channels and toward writing, reasoning, wrestling with ideas, praising, hoping, questioning.

How do the circumstances surrounding the Executive Order Promoting Energy Independence and Economic Growth echo the events of Pasolini’s dangerous masterpiece?

With the tone and care of the genuinely righteous, his voice was that of a herald, with writing that sliced through hypocrisy and the specific, tragic banality of American life with a swift condemnation that managed to touch the sublime.

Staying Vertical is an aggressively conceptual cycle-of-life saga that brings the director back to his earlier model, in which characters ramble through a freeform narrative with no fidelity to logic.

Films as disparate as Altered States, Nosferatu, 1984, The Night of the Hunter, Repulsion, Tetsuo the Iron Man, M, and Sette note in nero are placed on the same emotional plane, each an evocation of all-purpose, free-floating, indefinable anxiety.

If good art has to on some level be working against something then lately Jarmusch, with this film and Only Lovers Left Alive, seems to be valiantly fighting time and tide. In his ever gentle way, he has found a new urgency.

A Few Great Pumpkins

La Jetée, I Walked with a Zombie, Creepy, Jacob's Ladder, Young Sherlock Holmes, Vampyr, The Pit and the Pendulum

Directed with a rare combination of aesthetic vigor and emotional delicacy, this is a film that resonates in our culture and moment not because it was manufactured to matter, but because in its every breath it has clearly stayed true to itself.

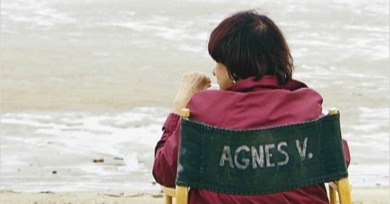

One Sings may ultimately be gentle in its politics, but Varda could probably never make a truly mainstream film: her artistry is too exquisitely singular, too intrigued by moments out of time and the unspoken words between people that can only be expressed through abstraction.

In selecting the subject of our latest director symposium, we alighted upon a figure of constant surprise, of reinvention, of charm and oddity and intellectual freedom. She is one of the most thrillingly alive filmmakers working today, and she is 88.

There is nothing here that comes close to the subliminally effective terror of the original. Instead, Wingard expectedly goes for full-throttle, high-decibel horror, amping up the Blair Witch model for the ADHD generation, providing an endless array of false scares and loud crashes.

It has no intention to disrupt its audiences or get them to question their own notions about death and mourning. Nor does it need to: Moretti’s film is no less personal for being straightforward in its aims, sketching a fleet portrait of the difficulties of balancing personal challenges and professional goals.

A filmmaker, like Loznitsa, may use the camera to frame unscripted events to place them within understandable linear frameworks; another, like Malick, uses it to liberate ostensibly scripted events so that one can get at deeper truths behind the images. Maybe cinema exists somewhere in the middle.

The exteriors were shot on 65mm film, the interiors were captured digitally, and they offer different kinds of rapture, the former taking in the vastness of the land with hushed, God-like awe, the latter almost unbearably human, hunkering down in the burnished shadows of rooms sometimes lit by a single candle.

Why are we suddenly so obsessed with questioning cinematic reality? Why “docs”? And why now? To get at these queries, and try to get a handle on the nonfiction boom, we figured we’d do it the best way we know how: with a new symposium.

As with any good filmmaker, Mascaro uses the camera to help us see the world a little differently, a little more clearly. There’s something casually virtuosic about his new film, a work of strange realism that immerses the viewer in a natural yet defamiliarized environment of everyday ritual.

-390x204.jpg)