Michael Koresky

Weekend, Une femme mariée, Le Gai savoir and Un Film comme les autres, Band of Outsiders

Breathless, Pierrot le fou, A Woman Is a Woman, Les carabiniers

The children in Rambow, set around 1983 or thereabouts, might as well be wielding digital cameras or pocket-sized cell-phone cams (and in fact, the film might have been less self-consciously precious had it been set in the present).

Why has a journal born five years ago on the cusp of digital explosion, such as Reverse Shot, only treaded lightly here until now?

The effectiveness of Take One is unthinkable without film itself: the audacity of the effects (split-screen images, little visual riffs in which the picture is contained in alternately enlarging and shrinking boxes) inextricable from the weight and burden of the equipment.

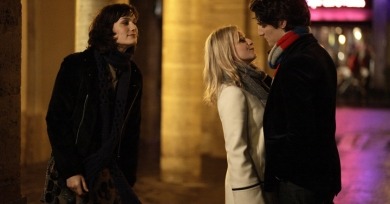

Love Songs is the brief dalliance to Cherbourg’s intense affair, perhaps too shy to fully take the plunge, but nimble enough to give off a flirtatious buzz.

There’s a tantalizing whiff of mediocrity to Boarding Gate, and it’s consistently set off by high levels of self-awareness and undeniable craft.

The entire project suffers from the gall Haneke shows in not only remaking his own film for the “edification” of a wider audience, but in trusting his own original vision so fundamentally and without question that he has chosen not to append or alter it in any significant way.

The Counterfeiters is the bread and butter of the Academy, not to mention film festival audiences everywhere, and as such, seems to have been designed solely to win plaudits.

Romero has often traded in rather glib social satire since the revelation of his 1978 Dawn of the Dead; whereas Tobe Hooper and John Carpenter’s genre work has mostly been greeted with retrospective praise and analysis, Romero’s never made any bones about his intent.

Once again, with his new film The Witnesses, great French filmmaker André Téchiné surveys the intersections of sexuality and politics, while offering up a compelling study in human strength and weakness.

As with his earlier Unknown Pleasures and The World, Jia Zhangke’s masterful Still Life is shot on digital video and skirts the line between documenting its nation’s transitional woes as it moves towards promised free-market independence, and creating fictional narratives around these events.

On a narrative basis, Forster and screenwriter David Benioff keep things moving briskly and fluidly, and the actors are emotionally compelling enough that it’s easy, in the moment, to overlook the film’s central thematic dubiousness and specious cultural elisions.

Like its protagonist, Jennifer Venditti’s acclaimed documentary Billy the Kid is both pretty hard to dislike and difficult to parse.

Though it’s both a predictable culture-clash comedy and a gentle plea for people of different political backgrounds to “just get along,” The Band’s Visit nevertheless manages to use its central contrivances and inevitable clichés to its favor, and becomes something ethereal and winning.

Point of view gets a major ocular workout in Julian Schnabel’s The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, which forces viewers to identify so fully with its paralyzed main character that even the peripheries of the frame seem like unapproachable boundaries.

To look at Van Sant's career monolithically, without taking his films apart one by one, does him, and film, a disservice.

No grand artistic summation or even a proper refining of pet themes and motifs, Paranoid Park finds Gus Van Sant further whittling on the same piece of wood. It must be a nub by this point.

So, then, as an experiment, naturally Psycho is designed to be a failure, an object lesson in the ebbs and flows of film history, as well as constant reminder of the endless fascination, terror, and ramshackle beauty of the original.