The Kid Is Alright

By Michael Koresky

Billy the Kid

Dir. Jennifer Venditti, U.S., Elephant Eye Films

Like its protagonist, Jennifer Venditti’s acclaimed documentary Billy the Kid is both pretty hard to dislike and difficult to parse. It’s already scooped up awards at Edinburgh, Los Angeles, and South by Southwest film festivals, and it’s easy to see why: this compelling, ingratiating portrait of some days in the life of a charming and troubled fifteen-year-old New Englander, with its canny intimacy and sharp editing, manages to be up-close-and-personal as well as safely discreet. Venditti, following around the not-quite-outcast teenager Billy vérité-style, is inoffensive in her intrusion, yet also manages to make the boy a compelling screen presence. What the film lacks in painful revelation it makes up for in the way it avoids exploiting its subject; and, refreshingly, in these days when most documentaries seem couched in meta-commentary, the film never falls back on the crutch of having the filmmaker’s ethical dilemma as a pivotal plot thrust.

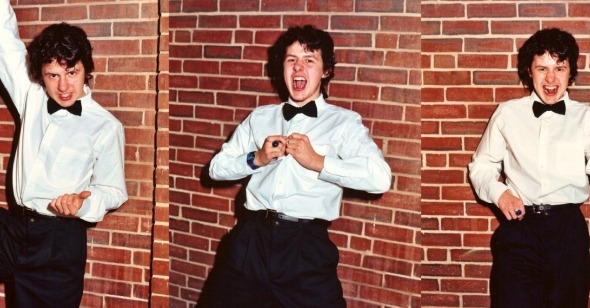

Billy is front and center, and a likeably intense central figure he is: more manic than brooding, he often comes across as any teenager making those first baby steps towards adulthood. Testing parental boundaries with his pragmatic, loving mother; just barely trying to figure out how to navigate high-school cliques; or, in the film’s fullest and most dramatically rewarding subplot, tenderly courting a prospective first girlfriend—Billy’s quandaries and rites of passage seem mostly mundane. Yet Billy’s also quite different from his peers, and not just because of some vaguely defined eccentricity; his slightly off-kilter inflections and speech reflexes sit side by side precariously with his highly articulate conversation, manner, and teenaged wisdom. Although his mother speaks of early misdiagnoses from psychologists and acknowledges her son’s difficulties in the face of an absent and abusive father, it’s never stated outright that Billy probably has a mild form of autism.

Where the natural confusion of youth ends and the syndrome begins is Billy the Kid’s appealing central unspoken question. Venditti strings together engaging scenes of Billy in his daily life, interspersed with shots of him talking to the camera, and punctuated by casual moments of insight from his mother. Yet with the film’s fly-on-the-wall removal, it’s difficult not to wonder how much the camera’s presence is affecting the events as they unfold, a natural question endemic to all documentaries of this form. While the circumstances of the shoot shouldn’t necessarily be part of this boy’s narrative, there’s a disconnect between what we’re seeing and why it’s being recorded and by whom. With cameras in their faces, his fellow students, seen in pool halls and cafeterias, seem mildly put off by Billy’s presence, yet also accommodating; one wonders if Billy’s slightly discombobulated social skills make him more of an outcast than we see on film. Furthermore, how different is Billy’s persona when the cameras are turned off? The camera’s presence is implicit, and only at the close of the film, when the project comes to a halt, is it foregrounded.

Yet Billy’s behavior seems so natural and purely his own that Venditti can’t help but capture his spirit on film. (Likewise, the small-town Maine setting is reflected with authentic feeling and is genuinely free of any regional condescension.) And if Billy the Kid leaves many questions unanswered, it also understands that to tag a definition on Billy would only be limiting. Billy remains an enigma in his own film; yet Venditti turns this gap into her film’s strength, choosing to normalize his plight as opposed to segregating the boy through movie-of-the-week victimhood.