Weekend

The classic long take traffic jam that closes out the first act of Godard’s Weekend is so monumental that it’s been re-created in miniature by artists Jennifer & Kevin McCoy in their sculptural installation “Traffic 1: Our Second Date.” Notwithstanding the obvious question—who goes to see Weekend on only their second date?—the existence of this homage and its circulation within the art world speaks to the canonization irony that MJR highlighted in his terrific post on Les Carabiniers. The sequence is virtuoso filmmaking, obviously, but the film as a whole, in which a sparring bourgeois couple head out of the city for a few days and end up reinvented amidst a Marxist cannibalistic maelstrom pushes the bounds of all those categories usually in play in the “Great Film” selection process: good taste, palatable daring, the touch of an author. Weekend has none of these things, yet somehow it’s been, correctly, labeled amongst Godard’s best films. People actually claim to like it.

Maybe by the time it had hit screens in 1967 writers were ready for it—with seven years of consistently surprising detours and detournements from Godard under their belts, perhaps the playing field and vocabulary had effectively been expanded. The first time I saw Weekend, having only seen Breathless, was in one of those a freshman year film seminar classes, that, enslaved to theory over history, eschews attempting an overall look at cinema for cherry-picked selections that matched whatever idea was under discussion that particular session. Not a bad context in which to watch Weekend, a film that consistently wrestles with the baggage of all the films that had come before it—shedding, rediscovering, shedding again—under the lens of a mélange of contemporaneous ideas ending up simultaneously placeable on a trajectory and utterly lost outside of context. It’s barely a “movie,” as the term is commonly understood, yet is, at the same time, more “movie” than one is ever likely to absorb in one sitting. Fin du cinéma indeed.

Godard wasn’t right—movies kept going, but I certainly wasn’t the same. Ma fin du cinéma. Overstressed and underslept, I nodded off for a few minutes about three quarters of the way through and awoke to find our “protagonists” landed in Marxist summer camp with little rationale. Animal slaughter, talk of Potemkin on the radio, the constant threat of violence—it’s the similarly intoxicating flipside of the primeval forest idyll of Notre Musique (at that film’s end, I tensed up, expecting a repeat).

The second time I saw Weekend was the very next night—I watched it again hoping for answers only to find out that there weren’t any, and to learn under Godard’s brutal, yet still comic tutelage, that answers need not be all we seek in the cinema, and perhaps should be the least valued of all. Even as the man pushes his audience away, he’s still hoping to draw closer to them, better them. Weekend makes good on the special magic of Godard’s sixties: the inexorable, airtight dream logic that undergirds his “narratives,” the sense that anything can, might, and will happen is no stronger in any of his films from that decade. If I’ve sometimes wondered if this voluminous period sometimes grows a little samey, a little didactic (for that reason, there probably won’t be a Godard’s seventies retro anytime soon—Comment ca va?—anyone?), it’s films like Weekend and Contempt that remind why we should care about this filmmaker above so many others.

So, then, what is Weekend? The classic example of “counter cinema”? A Marxist deconstruction of a Rohmer-esque narrative gone spiraling into wonderland? Utter nonsense? Give it a try and find out. —Jeff Reichert

Une femme mariée

Written, filmed, and screened at the Venice Film Festival, to much praise, as The Married Woman, Godard's eighth feature was then subjected to intense scrutiny by the French censorship board, who delayed its release by many months and enforced a title change to A Married Woman. It may seem like a minor detail, but the rationale behind the alteration—that the former seemed to make a blanket statement about all married women, especially rude in a story about adultery—says a lot about where the film was placed within the trajectories of Godard's career, the French New Wave, and film history generally.

Apart from its title change, the subject matter was perceived as lascivious, its attitude towards extramarital sex confoundingly vague, and its references to the Holocaust, and specifically an inference of French culpability, too controversial. This was 1964; Godard was 33, and his filmic approaches were changing; visually and philosophically he was moving into a new realm with The Married Woman, and he was moving quickly, on the cusp of a new cinema, not just politically engaged but forthrightly structuralist. The old New Wave approach wasn't suiting him anymore. In The Married Woman, we see the stirrings of the editing and photographic tactics he would be employing for much of the remainder of his 60s cinema: people as abstracts, dialogue as interrogation, direct address, whispered voice-over, billboards and advertisements as interstitial commentary. That all this comes within the ostensible context of a character-driven, mostly realist love-triangle shows Godard at once shirking off old constraints and diving into dangerous new waters. Of course the French cinema would respond with wildly varied reactions; though it's now, oddly, one of his less discussed films (at least in light of the more accessible genre plays—Contempt, Band of Outsiders, and Alphaville— that buttressed it) at the time it was popular, debated, and resolutely on the vanguard.

In form, The Married Woman seems informed by Godard's fellow New Wave leftist Agnès Varda's Cléo from 5 to 7, with its compressed time structure, its black-and-white X-ray-vision approach to a woman's quotidian experiences, and even its co-opting of pop imagery as political commentary (in this case, a stunning midfilm tangent in which Godard uses the entirety of a Sylvie Vartan song to accompany sexually provocative magazine images of bras and bathing suits)—the difference being that Godard seemingly casts judgment with every cut while Varda remained ambivalent toward her protagonist's journey through a commodified Paris. If Godard might be somewhat unsure here of how he's conflating the choices and situations of his main character, Charlotte (Macha Méril), with loftier notions of collective cultural memory and political engagement, the film is nevertheless a fascinating bout of wrestling with various philosophical ideas, a post-coitus plunge into the nature of contemporary existence.

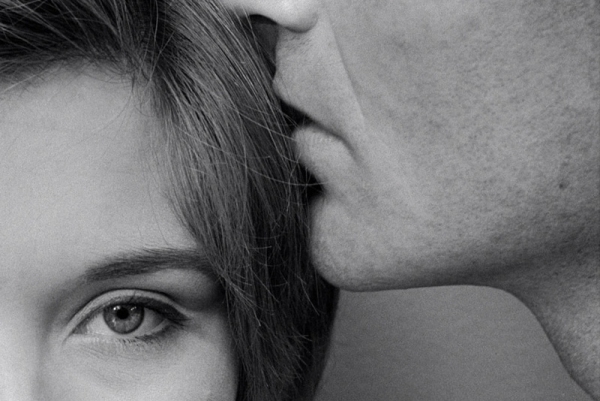

Godard directs all of his scenes with a stringent, modernist calculation, whether it's Charlotte lounging with her lover (Bernard Noel), as the two discuss the meaning of the word love, their bodies abstracted into elbows, knees, and arms against sheet-white backgrounds; Charlotte arguing with her controlling husband (Phillipe Leroy) amidst the hysterical cackling of an imported record, the camera gliding back and forth between two spacious rooms while hovering just outside their apartment; or in a terrific, beautifully composed single shot in a cafe, Charlotte covertly listening in on the conversation of two teenage girls discussing sex, while their words, obscured by the cafe's din, appear as hovering subtitles between them. Godard considers every set-up as a stand-alone art object, and every conversation as a clashing of ideologies. Many of the techniques Godard forged here would soon be put to ever more sophisticated view in works such as Masculin féminin and La Chinoise, but Une femme mariée still packs a hefty intellectual punch, and its climactic delineation of Charlotte's liberation (hopefully from both husband and lover, but it's left ambiguous) is memorable for its emotional pull. "It's a film in which something is missing. But this something is the subject of my film," Godard said. For the rest of the decade, at the very least, it seems like Godard kept looking for that elusive missing something. —Michael Koresky

Le Gai savoir and Un Film comme les autres

Heady, disorienting, and above all progressive—artistically, politically, socially—the late Sixties work of Jean-Luc Godard is known more by reputation than by first-hand appreciation. Seeing such rarely screened films as Le Gai savoir (1969) and Un Film comme les autres (1968) at Film Forum’s “Godard’s 60s” retrospective reaffirms why that is the case. Though wildly different in concept, content, and execution, both films are nevertheless supremely challenging affairs. While Un Film is aggressively distanced, verging on viewer-repellent (apparently some of Film Forum’s flabbergasted ticket buyers, echoing the film’s notorious New York Film Festival premiere thirty years prior, sought a refund), Le Gai savoir, though cheeky and lovely to look at, is non-narrative pastiche, reveling in Brechtian stiff-arms and dog-rousing sonic whistles. Both films seek a new language for film and for society in the months after May ’68, and as such both succeeded in offering a wholly fresh, if frequently inscrutable discourse. That audiences were (and are) bound to disengage from that discourse would seem to reveal the folly of Godard’s revolutionary project, but seeing these films out of the context of ’68—as hard as that is with such historically located texts—it’s apparent that failure was part of the philosophical expectation.

Built into Le Gai savoir and Un Film comme les autres is an acknowledgment of the impossibility their ambitions. Even as Godard pushes envelopes and audiences alike, he’s too smart not to consider the limitations of his form and discourse, too savvy to presume that words or images can well communicate the scope of his ideas, too self-critical to presume that propaganda—yes, even his own—will truly reach or persuade the masses. He’s too realistic to be idealistic, even about his own impassioned ideals.

Un Film comme les autres is indeed “like the others” in that there are moving pictures edited together and accompanied by sound, but otherwise the film strives to separate the viewer from any further familiarity with cinema. Several young people sit in a circle within tall grass near a dormitory/apartment/factory complex, their heads eliminated by the top frame of the picture so that inexpressive backs and arms and bent legs account for what’s visible. This static shot is periodically intercut with handheld documentary footage from the events of May ’68. The audio is an overdubbed translation of a conversation about those events and their aftermath, ostensibly conducted by those featured onscreen. Yet overdubbed doesn’t adequately describe the audio, which sounds like a hurried, unrehearsed recitation of a poorly translated (into English) transcript by a single, affectless voice, accompanied only by the faint ruffle of pages. Though I knew better, I still found myself looking back to the projection booth to spy our bumbling conduit, but alas he wasn’t live. Since one can’t delineate between different speakers’ recitations, it’s impossible to discern personality behind dialogue—though since we hardly see heads or mouths there wouldn’t be much to pin voices to anyway. It may seem like our monotonous monologuist is punishing us for not speaking French, but the low din from the original soundtrack suggests another layer of refusal—conversant voices are processed through a reverberating electronic filter, flattening all to a clamorous sameness. Though the conversation’s thus nearly impossible to follow, it should be noted that it’s conducted during the summer of ’68, deals with the aftermath of May, and considers ways forward for students and workers who participated in the general strike. About 45 minutes into the film, a title card announces the end of part one. With part two, the conversation continues, but features the same footage in the same sequence as part one, except this time the picture is ever-so-slightly out of focus. After another 45 minutes, the film ends.

Picture cedes ground to audio, conversation is reduced to recitation, recitation is foiled by imprecision, and an overwhelming amount of complex talk is heard as a maddening jumble. Expecting a down-and-dirty didactic trip to the summer of ’68, we’re left to stare at the flower patterns of a woman’s dress, watch a wavering blade of grass (later dearly missed in the second half’s blur), wonder at the context for dramatic documentary clips, and laugh at the absurdity of a messenger so thoroughly obscuring the message as to make it null and void. From an artist so thoroughly engaged in the politics of that time, the conveyance of that void is startling, and haunted me long after Un Film comme les autres ran its devious course.

As a friend said upon exiting the screening of Le Gai savoir directly before mine, compared to Un Film comme les autres, Gai is like a bowl of candy. Fashioned as an audiovisual primer for a society relearning how to see, hear, and make sense of the world, it features Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto as Beckettian figures on a black Brechtian soundstage, good-humoredly playacting a series of theoretically and dialectically motivated vignettes. They talk and pose, sing and shout, embrace and bicker, and perform slapstick representations of “Fascist Film,” “Funny Film,” and “Mozart Experimental Film.” At one point they play a deceptive game of word-association with a little boy and then an old, bedraggled man, while they themselves are constantly pestered and prodded by an offscreen voice (Godard himself, reprising his trademark distorted basso electro-god) who lays out a clearer—and drier—agenda. There are punny intertitles handwritten onto magazine advertisements and occasional intercuttings of Parisian street-scene documentary footage.

Ostensibly meant for French television, Le Gai savoir is an engaging assault of ideas, conceits, jokes, and propaganda tossed from one black box to another, deconstructing all that passes by while scrambling to find new sounds, signifiers, and meaning for a society primed to go back to zero and start anew. Godard’s pedantic basso inevitably elicits whispers of didacticism, but I’m yet again struck by how willfully ineffective the film serves as such. For how can a film be didactic if it’s impossible to fully discern from one moment to the next what’s being expressed? The film is constantly pulling us out of the familiar, overlaying sound to distraction, splicing up speeches and statements to create banal fragments, and simply providing too much—and too complex—information and stimulation for a viewer of even the highest cultural/political literacy to comprehend. As film, and furthermore as one-off television, one can’t possibly consciously absorb it all. For all its language, the film’s pointedly disjointed formality—like a zippy Sixties variety show further fractured to infinity—is paramount here, demanding neither adherence nor cooperation, just sharpened senses and a healthy tolerance for the indiscernible and unknowable. As expressed by Berto’s final reel lament that the film has been too “vague,” perhaps even a failure, frustration is of the very fabric of the project, while tolerance, then as ever, is hopelessly self-selective. —Eric Hynes

Band of Outsiders

Well, there's the dance . . . the Madison. And there's the mad sprint through the Louvre . . . nine minutes, the new record. But for me there's no set piece in Band of Outsiders that can equal the dazzling effect that is Anna Karina's face. At this point she was far from her early days as a model, getting several years' worth of quick and cruel lessons in life and art from Godard; in Band of Outsiders Karina combines her natural wide-eyed angelic charm with an increasingly frustrated, worldly pragmatism, and it's a winning, poignant combination. Her Odile, named after Jean-Luc Godard's deceased mother, is hardly a naif, but you can tell she's been used to playing one. As Godard wrote about her, "She lives, on the contrary, each day as it comes, each emotion as it comes, which she plunges into one after the other."

When embroiled in a simultaneous criminal endeavor and love triangle, with Sami Frey's collected yet fiery Franz and Claude Brasseur's deceptively hangdog and simple Arthur, Karina's Odile lights up with promise, excitement; perhaps Franz and Arthur's silly plot to steal from her wealthy aunt will provide her with the sort of foolhardy fun that one sees in the movies. Yet like Godard by the time he made Band of Outsiders, perhaps she's beyond buying into that kind of escapism ("Why a plot?" she asks, directly to camera).

Reality doesn't exactly come crashing into their little scheme (though it is filmed with a realist aesthetic, and using Godard's most conventional film grammar since Breathless), but there's something inescapably tinny and perfunctory about their gains. Band of Outsiders is often described as "lighter than air" or a "lark," and with its can-do New Wave attitude and lovely, languorously insouciant threesome, it surely is a hoot to watch, but its grey-sky sadness always seems to me as pronounced as its joy. Perhaps, even more so than in the violent turn of events, this mostly comes from the constant push-pull of Karina's Odile; as Godard must have seen Karina as a source of happiness and despair at this point in their tumultuous relationship, he also makes Odile into his ideal—a Karina whose sadness he knew he might not be able to puncture much longer. She responds by staring back soulfully. —MK