Reverse Shot On Demand

Are we merely “diaper dandies” (thanks, David Poland!) rattling sabers to grab the attention of the establishment? Or is there something to the way we grew up with movies that results in a different way of looking at them?

Undeniably, the age of video spawned our current state of being accustomed to having “everything” available to us at all times. Film history (in theory) no longer has to rely on rare screenings or archival digging to advance: previously hidden treasures are spilling out at our feet seemingly every week.

Wayne’s World met with its audience at the perfect late-capitalist moment—a product to satisfy evolving marketing strategies, the film ornaments corporate ideology with self-conscious irony, fostering its audience’s dependence on popular culture by selling it as above-it-all satire.

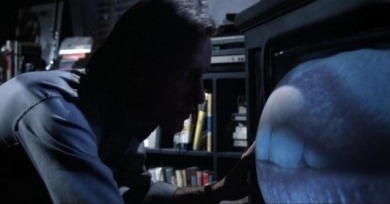

Cronenberg’s choice for the site of the revolution is a public-access cable channel innocently called “Civic TV”; it’s there that Max Renn (James Woods) gives his audience the hardcore sex and violence that the cathode ray tube had previously lived to deny.

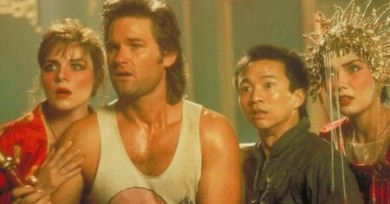

The video store cult section buried John Carpenter. His hour-and-a-half revelations were always modest, and he got the movie he wanted every time. No talk of director’s cuts, no commentary except about paid bills.

In one sense, my descent from lofty aesthetics to base pleasures, from unsettling ambiguity to simple rapture, and from intellectual engagement to visceral thrill, flies in the face of expectation: Don’t we respond more powerfully and more deeply to works of art upon repeated exposure to them?

The John Hughes generation didn’t care a whit about aspect ratios or screen size. They cared about laughing and about feeling smart while laughing, and they cared about relating. Home video and cable television only made it easier to connect, to own the connection and revisit it at will.

Wild at Heart is, for all its confounding detours, simply this: a gorgeous love story set in a hyperbolically fucked-up world.

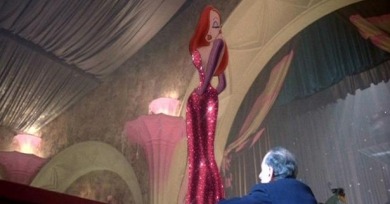

I owned Who Framed Roger Rabbit—we use this sort of discourse even now, though we usually acknowledge the essential facsimile nature of home video by throwing the words ‘a copy of’ in there.

It’s difficult for me to think of a more proper introduction to the confounding, slack-jawed pleasures of this ostensible space saga than crouched on the floor, behind my parents’ hassock, on the carpeted floor of my childhood family room.

For a child aged five or six, the Rebel Alliance’s cascading near-failures turned miraculously into grand success was the perfect agent of cinematic wish fulfillment—a narrative culminating in total satisfaction with loose ends firmly tied in a fantastic Endor hoedown.