Memoirs of an Invisible Man

Nathan Kosub on Big Trouble in Little China

The video store cult section buried John Carpenter. His hour-and-a-half revelations were always modest, and he got the movie he wanted every time. No talk of director’s cuts, no commentary except about paid bills. But the moment Carpenter’s movies took on the aura of rediscovery—the second life of small-screen resurrection—their creator changed. Instead of blockbusters, he directed knockoffs, which in turn spurred declining ticket sales. There is a quote attributed to Kurt Russell, difficult to document, that gets at the heart of Carpenter’s folly: “If it hadn’t been for videocassette, I may not have had a career at all.”

If it’s accurate, it’s a shame. The characters Russell played for Carpenter (R. J. MacReady in The Thing, Snake Plissken in Escape from New York, and Jack Burton in Big Trouble in Little China) belong in movie theaters. Carpenter made movies for crowds, for opening weekends at multiplexes. King Friday. And when he no longer could, his movies suffered; Ghosts of Mars, his last feature, is so miserable that not even tenacity can excuse it. Instead of a household name, Carpenter became the paragon of directors’ shelves in video stores nationwide. And he perished, in a way. Success on VHS is a graveyard for a man who wanted to see his movies with sold-out crowds. The more adamant his fans, the smaller their multitudes, distilling with their praises the essential plangent sigh: numbers, not anonymity, made Carpenter great.

Something should be said, then, for his most underrated film. Big Trouble in Little China is his lightest success, carefree with its own mythology and expansive in its gifts—the soft-shoe his horror triumphs couldn’t inherently manage. Carpenter wanted to be a Forties holdover, and that meant tackling pulp material with studio backing and auteurist verve. In 1978, he told Sight and Sound, “If I had three wishes, one of them would be ‘Send me back to the 1940s and the studio system and let me direct movies.’ Because I would have been happiest there.” But, as Sheldon Hall points out in his essay, “Carpenter’s Widescreen Style,” Carpenter loved the revelations of modern cinematography too much to have ever been at home in the Academy ratio of Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock. “I just love Panavision,” Carpenter said once. “It’s a cinematic ratio, and I don’t think you can see it anywhere but the movie house. On television, you see squares and that’s fine for television.”

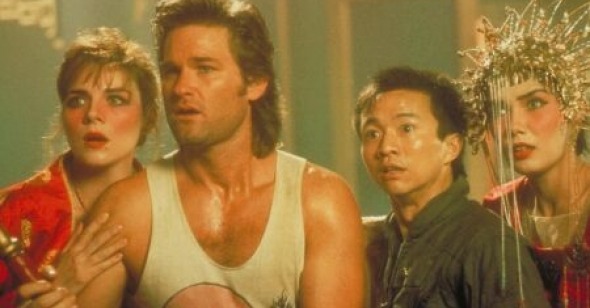

The comic low-key star persona and the Temple of Doom hijinks of Big Trouble in Little China, (like The Thing or Assault on Precinct 13), were not necessarily new. Even the idea of sidekick as hero (in this case, Dennis Dun’s Wang Chi to Russell’s Jack Burton) is rooted in the class romances of the Thirties (Platinum Blonde, say, with or without Loretta Young’s roundhouse kick). But it opened nationwide, and remains the defining moment in Carpenter’s decline, insofar as it’s so good.

Unlike his earlier Escape from New York and The Thing, which both starred Russell, Big Trouble in Little China lost a lot of money. The film’s financial failure effectively gutted Carpenter’s future budgets and relegated his projects to a cult status very different from the B-movie reputation he assiduously courted from Assault on Precinct 13 onward. Big Trouble in Little China feels important now against what came after: the turning point from great to bad.

The movie was initially conceived as a western, but modernized by the director to San Francisco’s Chinatown. How significant that Carpenter, who claims to have always wanted most of all to make a western, was presented with the tailor-made option but chose not to: a sure sign of the forward-thinker, not ready to fall back on his earliest ambitions just yet. It remains as quotable a movie as there is, full of odd asides, a sense of humor just behind the pacing (almost lackadaisical), and possibly the most patriotic toast to America’s armed forces since Donovan’s Reef.

Big Trouble in Little China is the all-American rabbit hole, full of intrepid female journalists, flashy restaurant managers in Chevy sedans the size of big-rigs, and tour bus drivers (“bus for tourists!”) as the transcendental sages of the hour. A fringe mob battles the forces of evil with all the merrymaking slack of a sub-culture indifferent to its own achievements; only the inevitable destruction of a city block clues in the outside world. Even then, no one believes the story about magicians and gods and underworld spirits. The spectacle is there for us alone, faithful to the myth of romance in the guise of an impossibly big Freightliner creeping through the narrow alleys and produce stands of backstreet Chinatown.

It’s the best of Carpenter, if not the scariest. Burton is enough of a loner to exit the movie without his gal Gracie (Kim Cattrall), but the Hawksian camaraderie makes room for a moment of sympathy between hero and antagonist. “You seem to be one who knows the difficulties between men and women,” David Lo Pan (James Hong) tells Burton, his prisoner at the time. “How seldom it works out.” Burton, at first, is in it for the money; he thinks if he loses Wang, he loses his earnings, too. Wang’s after a girl, Egg wants closure, and Margo (Kate Burton) wants a story. Lo Pan wants a wife with green eyes (to break his curse), and the curse is a screenwriter’s freedom: free to be hare-brained and bold. There are lots of little touches of that joy: the wicker chairs that Burton and Wang are strapped to, like invalid extras from the house of Sternwood in The Big Sleep; the Hell of the Upside-Down Sinners, a tidy homage to the rot in The Fog; and, of course, the dark and stormy night that gives the story its context of isolation and dreams.

Big Trouble in Little China, like Escape from New York, is a dodge against type: Carpenter not as a master of horror (since Halloween, that has been his burden), but an entertainer in the broadest sense. In Big Trouble in Little China, Carpenter gets the college humor of Dark Star, the special effects from The Thing, and an antihero who (unlike Plissken) wants to live in the world he saves. The movie is a craftsman’s holiday, sending our eyes languidly to the corners of the screen while our hero wrestles for his life with street gangs and demons. More importantly, the film has not dated; its homages are reinventions, its script a rejoinder to cynics and pretenders, and its heavy heart the soft landing for the excess in its fun.

It also looks great. Excluding Assault on Precinct 13 (shot by Dark Star alum Douglas Knapp), Carpenter’s best films (Halloween, The Fog, Escape from New York, The Thing, and Big Trouble in Little China) were all through the lens of cinematographer Dean Cundey. Cundey pairs interiors with exteriors like no one else in the eighties, conjuring not just cold and fog but the humidity inside the cab of an eighteen-wheeler and the warm smells of a well-lit kitchen. It’s easy to talk about Big Trouble in Little China as a rainy night’s worth of wind-swept alleyways, only to hear your friends compare it to a Mask of Fu Manchu funhouse (though there are fates worse than that): so much clutter and color might seem gaudy instead of evocative. The climactic wedding ceremony, especially, bears more than a passing resemblance to a holiday-season shopping mall, the cavernous room full of brightly attired foot-soldiers waiting for the main attraction to descend his pink neon escalator to the floor. What’s remarkable, though, is the way a Chinatown warehouse and its subterranean passageways become an organic, haunted maze, through which our heroes wander and backtrack, only to uncover upon returning a new door, a new room, a new way out or in.

The rooms themselves—torture chambers, security stations, penthouse suites—gather dust, fill with light and then dark water, and encourage the camera to rest in corner kitchens beside windows, near tables with bowls of food and half full bottles of beer. In spite of the madcap urgency (there is always a timetable in the dark arts), Big Trouble in Little China allows for the generous reprieve of an elevator ride after miles of running. Elevators are so often uncomfortable in movies, full of tension and things unsaid (or else manic rendezvous), that watching Jack and his street-gang allies joke in subdued tones while riding in one is almost revelatory.

![]()

After Dean Cundey, Carpenter relied, by and large, on Gary Kibbe, who did his best but never managed the unified visions of Cundey’s precedents. Dean Cundey was an A-lister. So was Carpenter, until Big Trouble in Little China, after which his work became defined largely by the financial restrictions he articulated in increasingly personal, frustrated storylines. When the low-budget Prince of Darkness (his follow-up to Big Trouble in Little China) lost money in turn, Carpenter called it too intellectual. Yes, the physical manifestation of the devil’s second coming makes a neat homage to Cocteau, but the movie plays more like a timid concept without a thoughtful execution, and it runs out of steam before it even approaches halfway.

His next film, They Live, bears the scars of a cult classic but is too indiscreetly autobiographical, in spite of Roddy Piper’s rowdy full-press take-downs and the great opening credits. Those are as much a benchmark as anything; even the wet-towel Starman begins with sinister panache, a cold opening more akin to The Thing than E.T. . Before They Live, a Carpenter movie was always worthwhile for the way it began; afterwards, the opening montages were rarely more than a credit roll. The rest of They Live, however superficially a tip of the hat to fifties sci-fi, is mostly thinly veiled anti-studio metaphors—no warning against Big Brother, but instead the Powers That Be that crush the creative freedom of big-minded directors. The aliens are suited bureaucrats who don’t give the protagonist any credit. Piper’s best retort is a middle finger to the camera; how easy to imagine a “take that, you bastards” off-screen.

And briefly, briefly, Carpenter seemed gone completely. Memoirs of an Invisible Man is the only Carpenter film where the title is not preceded by “John Carpenter’s,” as if, in keeping with the hero’s plight, all authorial content stayed anonymous. The film is also, I think, the last time Carpenter displayed any technical innovation, however picked over: Sam Neill’s face in the window between cabins on a train, the complexities of navigating a knife and fork when you can’t see your hands. Escape from LA defies the Snake Plissken creation so completely as to render Carpenter the Pizza Hut of modern moviemaking: any gimmick in the name of a sale. The go-to scene is Plissken surfing, but at least there’s something bizarre in a leather-draped Kurt Russell hanging ten beside Peter Fonda’s umpteenth variation on his own lost youth. The worst of it—the very worst—is Plissken playing basketball in a gladiatorial contest against the shot clock.

And so on. In the end, John Carpenter grew old in the way that young people inherently fear and hope to avoid. But Orson Welles was right, you only need one, and if the inclination is to watch a movie like Big Trouble in Little China a little sadly, better still to let it be just what it is. For whatever reason, New York’s Film Forum didn’t include The Thing in its recent Ennio Morricone retrospective; one revisits it instead on DVD. It can’t be bigger than the biggest screen in New York or Los Angeles, so it might as well be big at home. Anyway, I’ve always known them all at home. It isn’t really my battle to wage.

Still, one can’t help but feel that the fight deserves some record. I used to think that the John Carpenter who made The Fog could direct a screwball comedy as great as Ball of Fire. The hero wouldn’t be so different from Jack Burton; a little less macho, but not much (Jack is, if anything, a sweetheart). The woman would be a lot like Adrienne Barbeau, or, why not, even Kim Cattrall. Instead, Carpenter kept remaking Rio Bravo: with vampires, on Mars. Carpenter’s best movies are the heart on his sleeve. The worst are terrible, and one wants to understand why. How do you ruin the director who loved watching movies as a kid—a man invested in the culture of moviegoing?

Maybe home video gave new life to Carpenter’s years of box-office failures. After all, what’s better than Big Trouble in Little China to rent with friends? But Carpenter isn’t inherently a cult director. He seems like someone who might buy a ticket to his own show, then sit in the dark and watch the crowd. That was the song he wrote for Dark Star years ago: “they seemed so much kinder when we watched them, you and I.” And that’s what John Carpenter lost on home video: the big screen, the previews, the rows and rows of kids in chairs. He deserved better than his mirthless isolation, not for our sake, but for his.