Home Invasion

Travis Mackenzie Hoover on Videodrome

By most standards, the video and cable revolutions went largely uncommented upon filmically. Though broadcast television had been the sociological subject of films from A Face in the Crowd to Network, its influence had been far more conspicuous (and far more threatening to the movies’ bottom line): meanwhile the introduction of recording technologies and more “adult” programming via pay-TV was a development that remained culturally invisible. This is a remarkable omission: a paradigm shift that shattered the way movies were perceived and accessed was seen as no big deal by the movie elite, perhaps due to the fact that it created new markets for their product and thus there was nothing to mess about with in the product itself. If people were finding new ways to insinuate the product into their lives, why rock the boat by calling attention to the new world order?

But there was no peace in the republic. Film producers might not have been complaining, but more than a few outsiders were worried about what the new technologies had wrought. In my home country of Canada, feminists protested loudly at the dawn of its fledgling pay-TV industry when it was revealed that Playboy would be providing some of the content; in Britain, the notorious “Video Nasties” were blamed for various societal ills and were subsequently curtailed. Cases like this cropped up all over the video-saturated world; clearly, there was more at stake than whether people were going to watch movies at home. The question instead was which movies, what audiences, and what consequences to such a combustible combo?

Still, there was the sense that the protests were culturally marginalized: they existed too much in the realm of reality, not the fantasies that were now permeating our lives thanks to the increased televisual choices and the more-now-better pace of viewership on demand. The issue wasn’t exactly that of content: the medium itself had become the message, weaning us off the authoritarian cultural gift of network TV and encouraging the viewer to actualize fantasies in their own way in their own living rooms. It is this choice—not the chance encounter of audience with smut but the ability to reach out and grab it regardless of broadcast regulation—that made the accessibility of the video revolution so completely subversive and so potentially dangerous to certain ideological persuasions. The irony is that as this was happening, we were being taught by the product not to notice it; the conversation was being driven outside of the realm of the technology being discussed.

Enter David Cronenberg. Having been on the vanguard of the exploitation market early on in his career, he was poised to benefit from these new channels of access and the freedom they afforded; he was also no stranger to censorship battles, having been denounced in the House of Commons for his sex-slug horror movies and driven from his apartment by a disapproving landlord. This makes it all the more perplexing that he would make as his first masterpiece Videodrome, which threw into confusion both the pro-video and anti-video positions while setting them both in sharp relief. To be sure, he’s on the side of the subversives in the battle for hearts and minds, but he’s also aware of the enormous changes we were visiting on the body politic and the way reality was to be constructed. And it’s not all candy and roses on the road to “the New Flesh.”

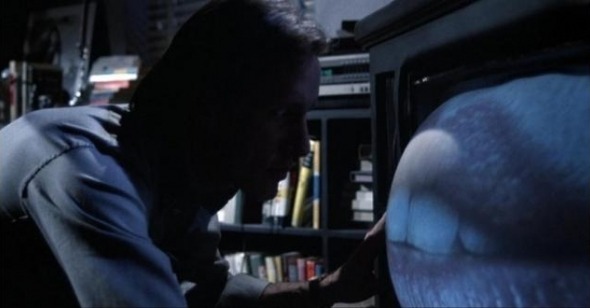

Cronenberg’s choice for the site of the revolution is a public-access cable channel innocently called “Civic TV”; it’s there that Max Renn (James Woods) gives his audience the hardcore sex and violence that the cathode ray tube had previously lived to deny. It’s important to notice the mom-and-pop nature of the enterprise: this is not some faceless corporation disseminating pictures to a large market, it’s a sort-of small businessman undercutting everything a large network represents. The niche-market king is of course trying to stay one step ahead of his viewership, and is thus thrilled when his head technician Harlan (Peter Dvorsky) latches onto a signal for a show called “Videodrome.” The show offers no plot and no “characters” beyond hapless victims who are tortured and electrocuted by master-tormentors covered head to toe in protective gear; “it’s what’s next” is Renn’s motive for subsequently searching out its producers in order to show it on Civic TV.

But he’s not playing at the level of the program. After being warned of the show’s possibly being a snuff enterprise by softer-hearted porn producer Masha (Lynne Gorman), the older woman tells her scheming counterpart: “It has something you don’t have, Max. It has a philosophy—and that’s what makes it dangerous.” Max is a delivery system looking for content; “Videodrome,” it turns out, is content looking for an audience. Late in the film it is revealed that the show has been masterminded by a group of moralists at a corporation called Spectacular Optical and run by a man named Barry Convex (Les Carlson); they’re determined to run a signal through the program that will induce brain tumors in viewers, thus taking their potential corruption out of society. To do this they need to seize control of Civic TV and gain access to its slice of the market; thus Max is used as a guinea pig and a puppet for eliminating his partners and handing over the reins so that they might implement their scheme.

Still, it’s not as simple as content vs. censors. The “Videodrome” signal was created by Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), the film’s McLuhanesque visionary, who exists only on video; he claims “the battle for the North American mind will be fought in the video arena.” Proving this is the fact that his former partners at Spectacular Optical used the signal to kill him once he figured out their ultimate aims. Where Convex is cynical and moralistic, O’Blivion’s quite bullish about televisual technology: he claims that, technically, “television is reality, and reality is less than television.” What’s important to note here is that O’Blivion is talking not of the content of television: as with McLuhan, the medium is the message. And the message at this point in technological history is one of choice, undermining years of acceptance of what comes down from the network ether.

It would have been easy to leave it at that, but Cronenberg complicates things by revealing the power of the individual cultural products. Having received the “Videodrome” signal, Max begins to hallucinate wildly—and develops a vaginal slit in his chest, where Convex can insert throbbing videocassettes to send him on murderous missions. Thus he’s sent to kill his partners, give Civic TV to Convex, and kill Brian O’Blivion’s meddlesome daughter Bianca (Sonja Smits). But Bianca, who is one hundred percent for the new technology (and even runs a “Cathode Ray Mission” where the homeless can watch television), deprograms Max and inserts a new program to kill Convex and extol McLuhan’s extensions of man in the form of “the new flesh”. It’s clear that possessing the technology is no guarantee that you’ll be free of orders—you could just be programmed by smaller bodies. And so the matter of living on video continues to be a battle for hearts and minds, of various ignorant armies clashing by night over the right to control whatever atomized delivery systems are scattered across the landscape.

Cronenberg remains undecided about the desirability of the whole transformation. On the one hand there is the subversive potential for the new formats and media that would allow the viewer to determine his or her own viewing diet; on the other hand is the inevitability of culture to “have a philosophy” and that “philosophies are dangerous.” The end of the film finds Max having not only destroyed Convex but also destroyed himself: wanted for murder, he visits a condemned vessel in Toronto harbour and hallucinates a vision of a television set showing old girlfriend Nikki Brand (Debbie Harry), who also became one of “Videodrome”’s victims. She says that the body is not enough; one needs “total transformation,” and the only way to transform is to destroy the human body. Max points the gun at his head, intones “Long live the new flesh,” pulls the trigger, and ends the movie. We don’t see his transformation; we’re too early in the video revolution to know where that concept will end up. But we are giving up the way we have perceived ourselves through technology, and there is no turning back. Whether it was the right choice is something only the future can tell.