Reviews

Marriage Story confronts the nature of divorce as a dehumanizing, lucrative institution: probing not just its emotional dynamics but also its social, structural, and economic ones.

Seeking historical and temporal specificity ultimately proves fruitless, and provocatively so: The Irishman is, after all, based on an account of a subjective reality, an exactingly detailed version of one man’s perception of history, and of himself.

In attempting to say something meaningful about race and politics in the city’s biggest borough, Norton has fallen into the same pattern as many real-life real-estate developers and city planners, getting rid of what made the source material so compelling in the first place, and adding his own personally convenient plotlines in the process.

Though an adroit orchestrator of discrete scenes, Lapid has thus far struggled to construct wholly satisfying narrative containers for them. So if Synonyms stands as his most accomplished work to date, that is because it commits fully to an elliptical, disjunctive method.

Bong makes it clear from the film’s opening minutes that this is a movie about class. But what that means—and how that plays out through the Kims’ efforts to achieve a higher station—is never settled, perhaps, until the last shot.

No heroic Siegfried figure, Humberto is a feckless opportunist. And so his voiceover, which persists throughout the runtime, inevitably recalls the mobsters of Martin Scorsese, whose The Wolf of Wall Street Veiroj has cited as a conscious model.

Dedicated as it is to meticulous and unhurried character study that eschews subjective or sentimental identification, In My Room checks off most of the descriptors usually applied to work produced by filmmakers attached to the Berlin School.

Trouble has emerged at a particularly critical point for Northern Ireland, where violent sectarian tensions have been reinvigorated with the uncertainty spawned by Brexit. What Garnett’s film contributes is an acceptance of profound complexity in the face of belligerent binaries.

The possibilities and pitfalls of autofiction are on full display in Pain and Glory, the 21st feature from Almodóvar, notably the only living international filmmaker popular enough to be broadly recognizable by his last name alone.

By doing away with narrative tricks or genre bending, Desplechin puts the focus on the performances, which provide a multifaceted and devastating study of urban desperation.

Like Rod Serling, director Aaron Shimberg is eager to expose our own biases, and here he thrills at luring us into a vertiginous series of alternate dimensions, seeking to unravel our ideas about the nature of beauty captured on camera.

Shooting their dog protagonists in often exquisitely intimate close-ups of grizzled maws, fleshy gums, and weathered paw pads, the filmmakers foreground their curious status as semi-wild beasts that subsist both in the middle and at the margins of human society.

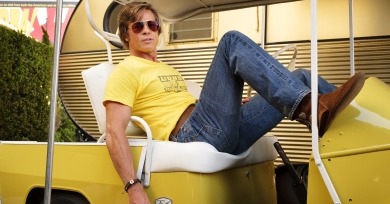

Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is overcast with melancholy and fueled by a rueful self-determination to overcome it. It’s on the surface his simplest film, but somehow his trickiest to talk about.

To begin with, designed as a one-director anthology film, it picks up and disposes of various narrative threads rather than staying with the same plotline or plotlines (or absence of plot) throughout. Secondly, it depends almost not at all on real-time duration to fill itself out.