Matt Connolly

In Uncle Boonmee’s world, daily human routines exist in a continuum with the mysteries of reincarnation, cross-species copulation, and the afterlife.

How do we square this web of physiological impulse, cultural connotation, and ineffable desirability with the almost-cheeky bluntness of Blue?

The way in which Lynch handles that severed ear offers a crucial hint as to how Blue Velvet simultaneously establishes these parallel worlds and destabilizes the boundaries between them.

Ironically, though, emphasizing the “surprising” depth or warmth (or whatever) in Magic Mike downplays what’s most intriguing about the film.

Brave has its problems, not least of which are an overreliance on the sort of yes-dear sitcom stereotyping that characterizes many of the interactions between the stern Elinor and boisterous Fergus. That said, I think it’s worth considering Brave’s particular concerns and cinematic predilections on their own terms

Corruption runs so deep in Chinatown that the elements themselves become a means to ill-gotten wealth, and untouched spaces are voids waiting to be filled by brutal, invisible forces.

The film has all the trappings of an archetypal Spielberg classic: fast-paced action spectacle; literal and figurative flights of fancy; the yearning for familial wholeness and the unearthing of youthful energy. That’s the problem. It’s a simulacrum of Spielberg wonder.

The Lovely Bones had camp escape hatches in Stanley Tucci’s wormy-squirmy serial killer and Susan Sarandon’s boozy grandma. We Need to Talk About Kevin offers no such exit from its suffocating vortex of self-serious exploitation.

Were Altman’s alarm bells not triggered by these ostentatious attempts at self-definition, or did he simply not bother to pursue this trickier line of satiric inquiry?

That patina of you-are-there atmospherics does little to sell the film’s stabs at state-of-the-union relevance.

Director Joe Johnston dusts off some of the mise-en-scène from his earlier foray into retro-futurist tinged action, 1991’s The Rocketeer. The Captain America costume has a particularly nice tangibility to it.

Puiu and Sergovici constantly block our access to Viorel, placing him in distanced long shots or half-obscuring him behind entrapping door frames and obstructive curtains.

One does not have to think hard to line up a lengthy list of small-budget comedies and dramas whose primary narrative thrust revolves around the trials and tribulations of a dysfunctional brood.

Those searching for fresh evidence that the collective obsession otherwise known as “the crisis of masculinity” remains alive and kicking: look no further than Hesher.

The expanses of the southwest have never felt quite the way they do in Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff, at once a summation of and an evolution in the director’s depictions of the American landscape—indeed, in her filmmaking overall.

A thrown punch or hurled epithet is never just itself in a film like In a Better World, but the key to understanding What Is Wrong with the World Today™.

Even more than Pedro Almodóvar, Todd Haynes, and other former enfants terribles of the queer filmmaking world, Gregg Araki seems caught in the double bind of maintaining outré street cred while simultaneously showcasing a more “mature” vision.

Dunst has some of the most dreamily sad eyes in movies today, effervescent when alight with joy and cutting when dulled by despondency; and she is matched in expressivity by Gosling, whose slightly weary baby blues offer flashes of the closely-guarded private worlds alive in his characters’ heads.

Resist the urge to check out of Tiny Furniture after the first twenty minutes. The winner of Best Narrative Feature at this year’s SXSW Film Festival (natch), writer/director Lena Dunham’s second film begins with enough self-satisfied tics to make even the hardiest filmgoer break out in indie-smirk hives.

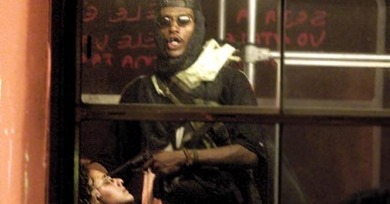

Who is José Padilha: clear-eyed chronicler of society’s forgotten souls, or misanthropic peddler of pummeling law-and-order fantasies? It’s a question implicit in the critical reactions to Elite Squad (2007), the Brazilian director’s fictional follow-up to his 2002 documentary debut, Bus 174.