Home Theater

As consumers of television and unwavering lovers of the art of cinema, we asked our writers to put the notion that “television is the new cinema” to the test.

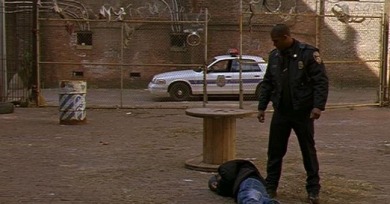

Despite The Wire’s density, it is rarely difficult to follow, yet—crucially—the dialogue remains free of clunky exposition. The logical conclusion to draw from this is that The Wire is a fine example of pure visual storytelling, which is surely a key facet of both successful television and cinema.

In Looking, (gay) sex is a storytelling tool, but it is always deployed in service of stories that see identity as rich and multivalent.

The airless, studied, nearly David Lynchian removal that seemed to typify the first season was also what made it uncannily fascinating. Though the show evolved, these negative feelings lingered. There is no sense of illusion in Weiner’s show, but rather a feeling of toxic plasticity.

The queen of these female antiheroes is Amy Jellicoe, whose return to her workplace after an epic, mascara-bleeding meltdown is chronicled in the tremendous HBO series Enlightened. Played by Laura Dern, Amy is exquisitely calibrated to be an irritant, but she’s also impossible to shake off or keep at a distance.

Awesome Show is the ideal work of art for a cultural moment in which cult appeal is manufactured rather than earned over time.

The show can be pathologically watchable when it dispenses with any pretenses to urban anthropology and plunges into its characters’ headspaces. Sometimes, the show’s depths are kiddie-pool shallow, but occasionally, as in “One Man’s Trash,” there’s a bit of an undertow.

Though A History of Violence and Breaking Bad follow opposite trajectories—one toward redemption, the other damnation—they both investigate whether the man makes the circumstance or the circumstances make the man.

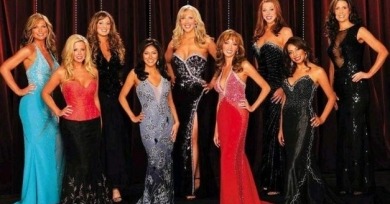

Saw and The Swan are only a decade old, but both now seem like relics from a time when it was a novelty to fixate on the body and its destruction; they represent blunt, perhaps unintentional, stabs at integrating ultraviolent, mutilation-based horror into a mass-audience aesthetic.

It was once said that 1950s French film critics discovered Shakespeare by watching Orson Welles; how many budding film writers would later discover Welles by watching The Simpsons?

The feature film is exceptionally effective at tracing movement and development, at dramatizing and helping us to make self-contained sense of journeys from there to here, then to now, who he was to who he’s become. By contrast, this episode of Louie starts, and stays, in the here and now.

Downton Abbey is constructed as an entertainment around the subject of class, but seeks to provide little substantial analysis, commentary, or political argument on it.

Mean Girls and 30 Rock clearly spring from the same comic worldview: a stylized yet curiously relatable carnival of spring-loaded insults, curveball cultural references, and moments of genuine empathetic connection self-consciously undercut by absurdism.

The Sopranos is always thinking of us viewers and our relationships to its characters. Constantly implicit is the question: why do we care about Tony Soprano? And more provocatively, why do we want to see this man better himself?

If the show traffics in lurid sex as a form of distraction, what are the real scandals being kept from view? Where might the actual crimes of this world, which is so closely modeled on our own, take place, and how might they impact us, the audience, if we dare to look?

Jane Campion’s seven-part series, which she developed with Gerard Lee and co-directed with Australian Garth Davis for BBC2 and the Sundance Channel, provides a limit case for disambiguating the presumed collapse of boundaries between television and cinema.