American Gladiators

Genevieve Yue on Scandal (episode: “Hunting Season”) and Primary Colors

Scandal is not the type of television show that aims for ambiguity. Unlike the tortured, and mostly male, antiheroes that fill the ranks of “quality television,” its heroine, Olivia Pope (Kerry Washington), and her team of “gladiators in suits” are unquestionably on the side of moral, if not always ethical, right. These Washington D.C. fixers—lawyers, mostly—reassure themselves every few episodes that they are the “good guys” while Olivia conspicuously wears almost exclusively white and very polished suits. To drive the point home, Olivia makes frequent reference to the wearing of a white hat, a metaphor made literal when she dons such a fedora at the end of an episode called “White Hat’s Back On.”

Is Scandal, now in its third season, what we would today call “quality television”? Probably not. For one, it’s not on cable, but on a network dinosaur, ABC, that serves a broad prime-time audience. It’s also a soap, deemed a lower, tawdrier, and more feminine genre, in which series creator Shonda Rhimes made her mark with Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice. Sober and serious quality TV, found in the more niche corners of cable, tends instead to suppress its soapier elements or enfold them within high-minded, sometimes literary pretensions. Though Scandal assumes the guise of a political thriller, what fuels the show is the adulterous frisson between Olivia and President Fitzgerald Grant (Tony Goldwyn). In other ways, too, Scandal falls short of the designation of quality: it’s sloppy, repetitive, and cluttered with plotlines as subtly rendered as the show’s visual symbolism. (Perhaps the problem of titling a show Scandal is its deadening flow of “shocking” reveals.)

Yet Scandal has proven immensely and addictively watchable. It has only gained in popularity since its debut in 2012, and rates consistently as one of the top television dramas in the United States. It may not be a quality show, or even something that rises above “guilty pleasure,” but it is undoubtedly a part of the national conversation, largely because it takes the nation as its subject. Responsive to current events, Scandal is intensely topical in a way that films can rarely be, and that television shows increasingly have become. Even period piece Downton Abbey, with a recent passing reference to the Teapot Dome scandal, has gotten in on the game.

As with the most sensational gossip that flanks grocery store checkout lines, the show’s scandals are most frequently sexual in nature. So far, we’ve seen a Republican politician who would rather be imprisoned for murder than use his gay lover’s alibi and lose his conservative constituency; a renowned civil rights leader who died atop his long-term mistress; a high-powered madam whose client list includes some of the most powerful men in Washington; a gay sting operation to out the vice president’s closeted husband; and three women who have been accused of conducting affairs with the President. The show’s central relationship is the on-again, off-again romance between Olivia and the President. Fitz’s marriage vows notwithstanding, Scandal has contrived an impressive list of reasons why the two can’t just get together, including a rigged election campaign, an assassination attempt, the First Lady’s pregnancy, Olivia’s other love interests, and all those other pesky mistresses. Surprisingly, one of the reasons not cited is the issue of race, despite the show’s unusual casting of a black woman as its central character. A rare mention of race, made perhaps as a response to the show’s critics, comes in season two’s “Happy Birthday, Mr. President,” when an exasperated Olivia says to Fitz: “I’m feeling, I don’t know, a little Sally Hemings–Thomas Jefferson about all this.” Fitz says nothing and looks stunned, as he often does: despite descriptions of him as a brilliant strategist, he’s usually brooding and sometimes drunk in the Oval Office, while Olivia, his Chief of Staff Cyrus Beene (Jeff Perry), and wife Mellie (Bellamy Young) work their schemes around him. In this scene, as so often happens, Olivia storms out, and the brief glimmer of critical insight is gone, drowned in the bright, garish glow of the week’s sordid scandal.

The show’s frequent recourse to “gladiators in suits” suggests a different dimension to its image of scandal. While Olivia’s team use the term in a heroic sense, they also unwittingly invoke its connotations of violent spectacle. Gladiatorial combats, as forms of art as well as sport, were lavish spectacles that edified the state. These were political theater, whether that meant glorifying the empire’s achievements or distracting the masses from its ills. What would it mean, then, if we assume the show takes Pope & Associates as gladiators in this second sense, not as heroes but as forms of entertainment used in service of the state? If the show traffics in lurid sex as a form of distraction, what are the real scandals being kept from view? Where might the actual crimes of this world, which is so closely modeled on our own, take place, and how might they impact us, the audience, if we dare to look?

We might say that these other scandals reveal the forms of power brokerage that, at every level of government, manipulate the democratic process in often subtle and unnoticed ways. The cynical view, one espoused by the moral universe of Scandal, holds that these are endemic to the functioning of government itself. Sometimes these abuses of power do appear on the show in hyperbolized form. We may get a rigged election and its conspiratorial cover-up, a shadowy spy agency that acts on its own authority, and the snuffing out of a Supreme Court justice with a pillow, but generally these storylines are neatly tied up or forgotten after a few episodes. These are fantasies spun from the headlines, nightmare tales of corruption too outlandish to be believed. And in that way, these murky dealings serve as the backdrop for Olivia’s crusading mission. The revolving-door crimes matter less than what they allow our heroine to do. Despite their implications for the democratic process, which they wildly trample, none of them threaten the integrity of the state, which corresponds to the rationale of the show. Though sometimes marred by a few metaphoric drops of blood, Olivia’s white hat always remains stylishly perched atop her gorgeous head.

Yet sometimes Scandal ventures close to our real world. With season two’s “Hunting Season,” an episode that introduced a massive NSA spying program, the show actually anticipated the Edward Snowden scandal by over six months; the episode aired on October 18, 2012, while the first of Snowden’s leaks came out in June 2013. (Many television programs, of course, have in recent years made use of government surveillance plots, including Damages, 24, Homeland, and Person of Interest, but rarely has a show been this prescient.) In “Hunting Season,” Artie Hornbacher (Patrick Fischler), a twitchy NSA employee, turns up at Pope & Associates railing against a massive domestic espionage program. Because he shouts and gesticulates wildly, stomping around atop the table as he investigates the hanging light fixtures for bugs, the team doesn’t initially take him seriously. When, however, he pulls out a thumb drive containing evidence of Thorngate, the NSA surveillance program in question, the latte-sipping ceases, and their voices lower. “It’s everything. Everything. It blows ‘We the People’ to pieces,” Artie says from his tabletop dais, his eyes wide. Olivia’s gladiators listen intently.

Unlike the response to Snowden’s leaks, which, for 47% of Americans polled by ABC, made “not much of a difference,” those in Olivia’s world are outraged at the NSA’s unprecedented infringement on the privacy of American civilians. As soon as a few intimate secrets are outed via Thorngate to Olivia, a TV network exec, and even the President, it becomes obvious that the program is too powerful and dangerous. Yet rather than going after the agency that conducted the program, or those that authorized it, the show finds a scapegoat in Artie, whose whistleblower routine turns out to be a fraud. Artie’s self-serving behavior takes the heat off the NSA, and Olivia’s team devotes itself to finding the recently absconded Artie before he can sell Thorngate to the highest bidder. Luckily, one of Olivia’s gladiators, Huck (Guillermo Díaz), tracks down Artie and Thorngate is returned, more or less safely, to the NSA. With the crisis seemingly averted, the surveillance premise was afterwards dropped, and Scandal returned to its soapy dramatics with no further mention of Thorngate or its potential abuses. To the extent that surveillance measures have persisted on the show in the form of bugs, wiretapping, or good, old-fashioned eavesdropping, they’re usually only tools to advance the plot rather than representative of a greater problem.

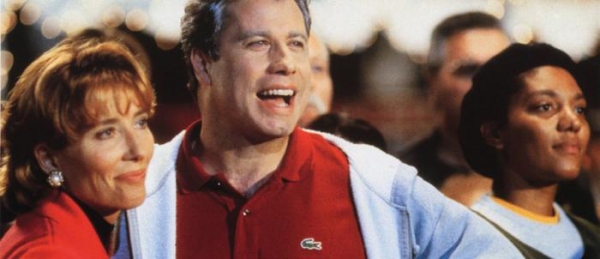

The mid to late nineties saw a flourishing of films that addressed the behind-the-scenes workings of politics, particularly where it concerned the manipulation of the media and the management of major scandals that plagued Bill Clinton’s campaign and presidency. Among these, Mike Nichols’s 1998 Primary Colors, based on the 1996 book Primary Colors: A Novel of Politics by Joe Klein (then published anonymously), stands out for its account of Clinton’s 1992 campaign for the Democratic Party presidential nomination. By the time of the film’s release, the Monica Lewinsky scandal was in full swing, and John Travolta’s depiction of Jack Stanton, a womanizer in the style of Slick Willy, though describing fictionalized events from six years past, seemed all the more pointed in the midst of Monicagate fever.

Henry Burton (Adrian Lester) knows full well the extent of Governor Stanton’s adulterous shortcomings, but accepts a position on his campaign staff anyway, believing the governor to be “the real deal”: someone who deeply cares about making a difference, someone who will make history, as Stanton’s wife Susan (Emma Thompson, in an improbable southern accent) insists. As with Scandal, Primary Colors pits Burton’s idealism against the muddier realities of the campaign trail, including multiple affairs, a sixteen-year-old girl’s pregnancy, and the deliberate smearing of an opponent by digging up the details of what resembles a Whitewater-like scandal. For a while, Burton accepts the scheming as an undesirable but necessary part of the political process. He reaches his breaking point, however, when the volatile Libby Holden (Kathy Bates), an old friend of the Stantons hired to ward off bad press, commits suicide for having played a key role in Jack’s ruthless drive to power.

Primary Colors is frank in suggesting that all candidates, even the upstanding Governor of Florida Fred Picker (Larry Hagman), must trudge through some amount of muck if they wish to get ahead. Picker, a late entry to the field of potential nominees, seems at first to be the kind of politician Burton most desperately wants to believe in. At a rally, he looks up at a wall of balloons released for the occasion, his expression verging on wonder. After a moment, he turns to the crowd shaking his head, “I didn’t expect this.” He stares out as if looking very far away, and levels with his audience. The entirety of the political circus—the media frenzy, the speeches, and debates—are, as he explains, like professional wrestling. “It’s staged and it’s fake and it doesn’t mean anything… it seems it’s the only way we know how to keep you all riled up.” Stanton’s team, standing in the crowd, is stunned. It seems that Picker might manage to speak authentically as himself, and not as a character in a political theater. Anxious that Picker might have taken the lead in the polls, his staff starts investigating his past.

Among Stanton’s campaign staff, Holden and Burton are most profoundly disillusioned by the muddying of Picker. They are devastated not by what they find, but what they’ve compromised of themselves, of their ideals, in the process. Even Stanton admits this, acknowledging the price that everyone has paid to get him the nomination. “You don’t think Abraham Lincoln was a whore before he was a president?” he asks Burton, who is giving his notice. Later, after Stanton wins the nomination, Burton stands among the crowd celebrating the victory, though it is unclear whether he has rejoined as a staff member, or is there merely as a onlooker who has seen too much to actively participate.

What a film like Primary Colors loses in immediate responsiveness it gains in reflective distance. It offers a calmer, more lucid perspective of the political process, compared to Scandal’s headlong dive into its vicissitudes. Libby Holden is crucial to Primary Colors for offering the long view on Stanton’s journey. She reminds Stanton of the way they started out, and how, regardless of an electoral outcome, they’d win “because our ideas are better.” On Scandal, there is no one nearly as thoughtful, or as morally sound, as her: though there are plenty of career politicians, few seem to have gained any insight comparable to Holden’s. Instead, Scandal offers an image of Washington where, as in House of Cards, vile and corrupt things happen as part of the scheming that takes place at the highest levels of government, and these problems are correspondingly “fixed” in these upper echelons. Where Primary Colors offers the perspective of an ordinary citizen whose desire to change conditions for the better prompts him to join the political system, Scandal entirely disregards the American people, at least as a civic entity. As a viewing and consuming prime-time constituency, of course, it feeds us all the sexual intrigue it thinks we want.

What is perhaps most far-fetched about Scandal is Olivia herself, firmly committed to the idea that she can “fix” anything. Like the orchestrated wrestling—or an update of those gladiatorial bouts—that Picker describes, Scandal makes a last ditch effort to clean up the sordidness of the political process by making it glamorous, sexy, and solvable by this fast-talking heroine within the span of a single episode. Though Olivia and her team are sometimes menaced for their actions, she rarely has to confront her own certainty in regards to the nobility of her intentions. Scandal suggests not only that this one-woman crusade works, but that we need Olivia, tirelessly fighting for our country’s democratic principles, even as she more than frequently bends the rules in her favor. Unlike Holden, who sacrifices herself for her vanquished ideals, or Burton, who, as a true believer, bows out of the campaign (at least temporarily), Olivia firmly believes in the rightness of her actions, whatever the cost. She is a true believer in herself.

Olivia’s dealings are, in fact, a major part of the problem: she “fixes” issues—including, with some frequency, the murders of numerous people—before they might, for example, go to trial, circumventing the procedures designed to affirm the efficacy of a liberal democracy. Even the attorney general, though he grumbles about it, is often willing to let things slide where it concerns Olivia’s conveniently unimpeachable “gut” instincts. And let us not forget, Olivia has the President’s ear on a special cell phone she reserves for him. The surveillance episode illustrates this situation unusually well. Though it makes appeals to the ideals of transparency, constitutional rights to privacy, and the integrity and autonomy of the press, the episode in fact undoes each of these: no one involved with Thorngate is ever tried, not even in the court of public opinion, as the television interview meant to expose the program is pulled at the last second. Instead the episode deals solely with one agency attempting to assert its authority over other branches of government, including the executive office. It portrays what is essentially a power grab at the top, and, beyond a few lines of lip service, it shows no real concern for the ordinary people such a surveillance operation would affect—namely, the very audience watching the show. In this and many other episodes, Scandal leaves no room for the actual workings of a participatory democracy. Not only is there no Libby Holden to serve as moral compass, there is no Henry Burton willing to work for his ideals. Scandal tells us that we, as citizens, are powerless, and must rely on Olivia to advocate on behalf of us. Olivia is uncommon in every way, not only in her ability to maneuver inside the Beltway, but, as we later learn, she was born into an elite political class by virtue of her superspy parents.

Because it is one of many prime-time TV programs to amass a wide audience—its season three debut counted 10.5 million viewers—Scandal might be understood as the modern equivalent of gladiatorial distraction. It obstructs or delays our attention to weighty issues by holding them at an unreachable distance, and gives us, instead, an array of dramatic intrigues. Though in the universe of the “Hunting Season” episode, Olivia’s gladiators are certain of the outrage the American people would express if they learned about Thorngate (and importantly, they never did), in real life the revelations of domestic espionage exposed by the Snowden scandal were largely treated with indifference. Perhaps this is unsurprising. The divestment, or disinterest, of American citizens with regard to the political process describes in large part a world that Scandal has helped to create. It’s not just that we, as part of the viewing public, are dazzled by televisual distractions—this, at least, is the show’s proposition, the rationale for its sensationalist fare. The ideology is bleaker still: in this world, where power is concentrated at the top, we’re told, and eagerly buy the notion, that our voices don’t matter.