East Meets West

The idea of doing an issue entitled East Meets West began as an excuse to write about our favorite new East Asian filmmakers, that batch of preternaturally gifted artists who have been flowing out of that “other” corner of the globe for the past decade.

Take away their very specific milieux and cultural reference points, and the responses between the two films would be remarkably similar.

To make the idea of a national cinema compelling, audiences need a body in which to locate the quirks and idiosyncrasies of that nation’s filmmaking—services that Ingmar Bergman, Abbas Kiarostami, and Akira Kurosawa each performed in their time.

Because of its prefacing epigram, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumiere has drawn a barrage of comparisons to Yasujiro Ozu. Hou dedicated his film to the occasion of Ozu’s birth centenary, but upon further reflection, it seems like a ploy to shut the public up.

The difference lies in the inner conviction which validates Kawase’s strategies, the lack of which saps the otherwise quite impressive power of Glazer’s.

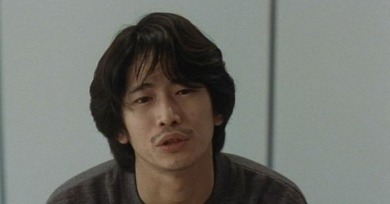

Lynne Ramsay and Shunji Iwai actually work hard to situate us inside their characters’ heads, or rather, between their ears, through a kind of headphone subjectivity.

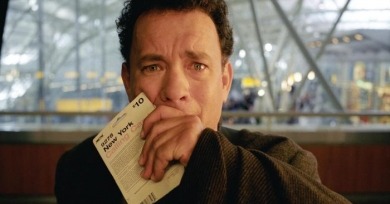

Sometimes films, whether by coincidence or by design, are joined at the hip, engaging in a dialogue and illuminating one another. Case in point—you can’t be amazed by Oldboy without considering its Hollywood counterpart, Kill Bill.

Many have pointed out that the 20th century was, above all, the era of acronyms—letters and dots standing in for something that remains ultimately in the dark. What they signify is never clear and is not supposed to be.

Slacker was nostalgic the moment it was made, expanding on same genre that American Graffiti invented. Mysterious Object at Noon has more immediacy, as we can sense the filmmaker’s presence just off-screen.

Both of these filmmakers look at the Wal-martization of the working classes and its relation to our xenophobic tendencies, exporting their ideas by utilizing large and burdensome simulacra.

The contemplation of the lonely life is hardly new in cinema, where it has been the shorthand for psychological depth in every genre from film noir to the romantic comedy to the epic biopic, and certainly not in the novel, where solitary confinement is practically a cottage industry.

Nothing is as simple as turning on and off a light, and thus Cure and Se7en offer a bad compromise between impossible alternatives.