Richard Linklater

"I never liked school that much, I never fit into any kind of academic program. I never liked official systems of any kind. Without even thinking about it, I just realized that wasn’t the place for me. I saw it as a long-term process, my filmmaking. I knew it would be a long time coming and I didn’t want to be humiliated right off the bat."

If there exists one piece of solid proof that aging gracefully is still a possibility in an era of sequels, prequels, and remakes, it’s Richard Linklater’s Before Sunset.

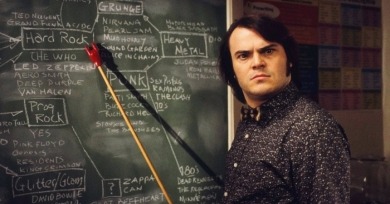

Instead of taking the easy road to reaction shots, the camera’s gaze is perhaps more than a little puzzled, but ultimately completely endeared of its subject, ridiculous as his compendium of rock star moves and clichés may render him.

Speed Levitch perhaps best embodies the central contradiction in all of Linklater’s works: he is a seamless cross-pollination of the infantile and the philosophical.

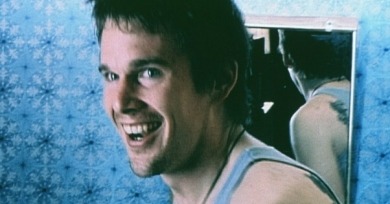

Aging. The gradual accruing of wisdom. The terrifying specters of immaturity and stasis. It’s the shag-carpet grunge of Linklater’s 2001 release Tape that paves the way to the sun-dappled Paris afterglow of Before Sunset.

In a sense, all of Linklater’s films are dreams in the way his verbose characters evoke alternate realities from an endless stream of thoughts, ideas, and stories, often engaging with those of others to create a sublime dialogue, nearly erotic in its hypnotism.

Put plainly, The Newton Boys is a film with the wind knocked out of its sails, and the enervating experience of actually sitting through it unfortunately blunts some of the value it does have to offer.

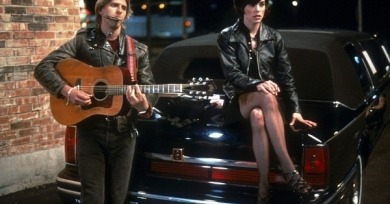

The America of SubUrbia is insular, separate from the rest of the world and wallowing in self-pity. And the ennui of suburbia has not changed: the 7-11 is still usually the only “public” space in town at which kids can hang out, the big box Wal-Marts and McDonalds still cannibalize the horizon.

It’s probably safe to say that no film ever found its audience better than Before Sunrise found the 17-year-old version of myself who went to see it on a first date in 1995. At the time, Richard Linklater’s name, if I had even heard it beforehand, probably wouldn’t have meant much to me.

In my callow teenage years, Dazed and Confused resided in that rarefied pantheon of movies prized less for their artistic merits than for what they said about me and my friends.

Finding an appropriate distance from Slacker is essential to acknowledging its achievement, which is due in part to Linklater’s own careful negotiation of distance from his characters and their ideas—which, more often than not, are elaborate arguments for distancing themselves from others.

For a movie that was directed, photographed, edited, written by, and stars Richard Linklater, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books is remarkably free of ego.