Tracts of My Tears

Joanne Nucho on SubUrbia

To the faded strains of Gene Pitney’s “Town Without Pity,” we see a montage of comparably dreary suburban landscapes. Strip malls, rock quarries, and gated communities in which all the rapidly erected houses look identically flimsy, all melt together in a sea of dry, brownish grey. The horizon is gutted, void, and empty in that way that makes it somehow more depressing than any apocalyptic big city sprawl. The opening shots of SubUrbia comprise what is surely the ugliest opening montage of any Linklater film thus far. Rather than setting the scene for a film about the suffocations of small town life (as the opening song suggests), the images reflect the emptiness, the void, the lack of any viable opposition to what passes for life in most American towns. Linklater asks in this adaptation of Eric Bogosian’s 1997 play: What could one hope for when every modern convenience, every need is met? Does one have the right to desire beauty or mystery when life is so “comfortable”?

In some ways, SubUrbia is a typical Linklater film. Taking place over the course of one night and revolving around a tight-knit group of young friends somewhere in anytown suburban America (in this case, the aptly named Burnfield), the film is in many ways the darker sequel to Dazed and Confused. In both films, the decade is more than just a backdrop—it’s the central character. Dazed and Confused was a portrait of a more homogenized small town in which the cultural codes were more concrete and the roles one was expected to play were more clearly defined. And their hope for the future, their unbridled hedonism, made them perhaps a little more innocent than the characters in SubUrbia. The joie de vivre of the characters in the earlier film reflects a radical difference in landscape; the teens have full reign over their town, and for one night, they are permitted to “own” their community space. The suburbia of the seventies doesn’t yet seem so controlled by corporate branding.

Nostalgia is void in SubUrbia. The kids in SubUrbia are on the brink of adulthood—they graduated from high school a year before this film is supposed to take place, but are still trapped in their town. Unlike Dazed and Confused, SubUrbia is a film about waiting, about hanging around and the slow dissolution of hope that something exciting is on the horizon. This isn’t a film about crushed dreams, it’s really more about the poverty of the dreams available—every possibility seems unappealing, so the characters are in a kind of stasis. This, one of Linklater’s bleakest films, is very much a product of its time, and one that carries an ultimate foreboding.

The America of SubUrbia is insular, separate from the rest of the world and wallowing in self-pity. And the ennui of suburbia has not changed: the 7-11 is still usually the only “public” space in town at which kids can hang out, the big box Wal-Marts and McDonalds still cannibalize the horizon. Linklater’s filmic representation of this play makes ugliness the main character. The kids in the film seem to take issue with the lack of control they have other their neighborhood. They wander through a world of invisible authority figures who shape their landscape without asking them what they think of it all—a Peanuts comic scripted by Beckett.

SubUrbia assembles its cast in the usual Linklater way—there is no one clear protagonist, though the hopeless and self-conscious musings of Jeff (played by Giovanni Ribisi) make him the most empathetic character in this suburban hell. Jeff’s girlfriend Sooze (Amie Carey), the dilettante feminist performance artist, and friends Bee-Bee (Dina Spybey), a recovering alcoholic, Tim (Nicky Katt), a violent and bitter ex-soldier, and Buff (Steve Zahn), a hedonistic buffoon, are the group of regulars who loiter outside of the local convenience store (much to the chagrin of Pakistani owners Nazeer [Ajay Naidu] and Pakeesa [Samia Shoaib]). It starts out as just another night in Burnfield, hanging out, drinking beer and talking about nothing. No one suspects anything eventful will happen, until Bee-Bee shows up and forces Jeff to admit that their old friend Pony, who left Burnfield to become a rock star, is going to meet them at ‘the corner’ sometime that evening. The group’s immediate reaction to this news suggests that the stillness around them is about to be disturbed.

Much of the beginning of the film is spent waiting for Pony to arrive. As Jeff continues to pace nervously around the perimeter of the convenience store, we begin to see a wisp of a dramatic narrative unfold. This is what Linklater does best—show that life happens while one is waiting for something. Tim makes wisecracks at everyone else’s expense and broods in the corner, drinking vast amounts of beer. Buff humps walls and cars, picks his nose and flails around like a child with ADD. Bee-Bee sits in the corner watching everyone shyly, a perpetual silent audience. Pent-up anxiety comes out in a foreboding, violent burst as Tim and Buff challenge and harass nervous shop-owner Nazeer to the point where his wife Pakeesa pulls a handgun on them. Nazeer talks his wife down, pulling her back into the store as the kids run away jeering. Only Jeff has any semblance of a conscience, attempting an ineffectual apology as he shirks away, ashamed of his friends’ behavior.

While Jeff sees no viable alternative, no original action or choice available to him, Sooze uses a passé expression for her inexplicable angst. Her clichéd feminist performance art, which consists mainly of a series of awkward gyrations and tap dancing steps set to chantings like “fuck all the men,” is emblematic of the “riot grrrl” archetype of the early to mid-nineties. Undoubtedly unaware that this purposely misspelled term was used to publicize pop groups like the Spice Girls, Sooze becomes a copy of a copy of a copy of the self-labeled youth feminist movement that is remembered mostly by its punk-rock associations (it tended to focus on music and handmade fanzines), a thoroughly grass roots, fragmented movement, made up mostly of middle-class, white suburban teenage and college-age girls, and not a centralized organization. A lot of this art was clichéd and—how to put this lightly—bad, expressions completely disassociated from their speakers’ own voices. When Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna got up on stage with “slut” written across her bare mid-riff, looking to usurp and reclaim the words used to chastise women noncompliant to societal standards, she unwittingly gave birth to an entire generation of girls unable to invent their own expressions of self-worth and who merely gave in to slovenly imitation.

Jeff is put off by her performance, and not just because he is offended by her saying “fuck all the men” whilst humping the air. He acknowledges her performance as a cartoon of feminism, a generic message that she doesn’t really understand. Sooze’s performance is recycled feminism, co-opted and decontextualized, a spectacular form that turns her into a caricature of a ‘strong woman’…more Tank Girl than Simone de Beauvoir. When he questions the meaning of her art, Sooze cannot respond. She runs down a list of -isms that she seeks to confront (racism, sexism, classism…) without really understanding how or why, or even being able to connect them specifically to what she does and the life she leads. Hilariously, Jeff asks her, “Do you even know one black person?”

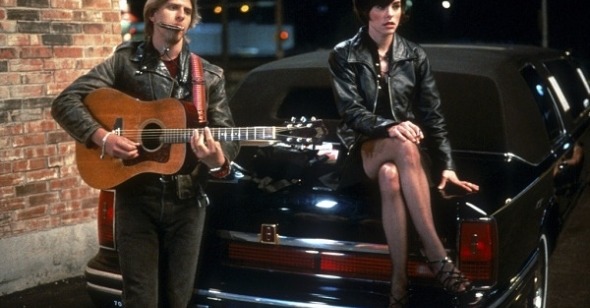

When Pony (Jayce Bartok) finally arrives in a ridiculous black stretch limo, everyone is thoroughly anxious to see him—Tim is armed with insults he is just waiting to hurl, Buff is completely over-excited (as usual), Bee-Bee hangs out in the background, and Jeff sulks as he watches Sooze douse Pony with flattery. As the characters start to mix, strange combinations collide and pair off, pulling the group in opposite directions. Bee-Bee watches on in horror as Buff (whom she had just “gone to the van” with) makes some predictably sleazy comments to Erica, Pony’s cell-phone wielding assistant (reliably chirpy-bitchy Parker Posey). Sooze sits cross-legged at Pony’s feet adoringly listening to one embarrassingly “earnest” acoustic song after another.

Boiling point is reached when Pony performs “The Invisible Man,” a ballad about dedicated to the “common people” of Burnfield. Jeff finally explodes in anger, calling Pony on his arrogance and insisting there is no difference between someone “commenting on life” and selling his comments to millions of consumers than someone like him living in a tent in his parents’ garage. Sooze and Pony do not agree, and from this point on there is a major shift of loyalties. Jeff may not see the difference between being a “loser” and being a “rock star,” but Sooze certainly does.

After getting fed up with Sooze’s shameless hero worship, Jeff comes to the conclusion that he isn’t really jealous of Pony. After all, his life is just another kind of routine, another compartment of the huge machine trapping them in their individual cells. Pony may occupy a slightly more opulent cell, but his limo is just as dull as Jeff’s pup tent. Perhaps in another time, Jeff’s observations may have been dismissed as sour grapes (which Bee-Bee, in fact, does). In the mid-Nineties, though, this backlash against the rock star image was prevalent enough to be eventually turned into a marketing tool used to ‘shift units’ to the very same alienated youth who fancied themselves part of the backlash in the first place. The marketing machine devours all in its path, and at some level, Jeff is the only one who somewhat understands this. There is no hope of an original action when everything is so easily co-opted, when every gesture can be used against you. This is the inescapability of American culture, of the suburbs themselves. Here, the group fragments into those who ecstatically embrace the stretch limo and its implied one-way ticket to L.A. and those who stay behind in Burnfield, either too cynical or too afraid to leave. The film concludes with a surprising climax—Bee-Bee, who has spent most of the film detached from and silently observing her friends is found on the roof of the convenience store, apparently overdosed on a combination of alcohol and pills taken earlier from her parents’ medicine cabinet. A horrified Nazeer looks on shaking his head and shouting:

“What is wrong with you people? You are so stupid! You have everything and you just throw it all away.”

Jeff looks up at him, unable to answer—this is the film’s central question. Nazeer’s final assertion seems ridiculous over the closing shots of the film: the sun rising over the gas station, the tract homes, the strip malls of Burnfield. Throwing all what away? Nazeer’s American Dream seems unfeasibly utopian compared to the withered, desiccated landscape that surrounds him. The white-picket fence has since begun to tip over, shrugging with disgust. The illusion of relative affluence has revealed itself; the drab colors, the flatness of the horizon, the wasteland of disused lots —this is the desert, a void, not some attainable oasis.

One can easily be both disgusted by and empathetic towards Jeff’s whining, because Burnfield really is a dump, but for Jeff there is only talk, no actions, not even daydreams of a better way of being. Jeff can’t even express the disgust he feels for fear of lapsing into clichés, into the realm of what has been done and said before. The tent in his parents’ garage is his own chalk outline—he’s no kind of hero. At best he’s a kind of infantile disassociated Virgil leading us into the depths of his own personal Inferno. And he can’t even do that right—Jeff doesn’t claim to have the answers, to offer any illumination. Without seeing any viable alternative, original action or choice available to him, he remains in stasis: he chooses to choose nothing.

In the end, as the group disperses, one cannot help but feel like no matter where they go and what they choose, they will still be wandering through neighborhoods and cityscapes of someone else’s design.