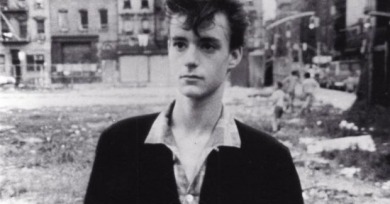

Jim Jarmusch: Dog Days

Jarmusch has widely been cited as a “minimalist,” an easy, often ill-used tag for someone who is much more interested in the big picture. His films luxuriate in set pieces, just perhaps not on an imposingly grand scale.

Jim Jarmusch, one of the last bastions of truly independent American cinema and director of the 2005 Cannes Grand Prix–winner Broken Flowers, is an elusive interview.

It’s literally the oldest story in the book. But what accounts for the enduring appeal of the voyage—what has made it, from Homer and Joyce to Spielberg and Kubrick to Mastercard commercials—such a persistent cultural trope?

Jim Jarmusch’s steadfast commitment to the swings of an eccentric sensibility defines his output to such a degree that I can as easily understand why someone would hate his movies as love them, in the same way you either mesh with certain personalities or don’t.

Not really terrible as much as inconsequential, Coffee and Cigarettes is so wispy it practically slides off the screen. Only audience good will and Jarmusch’s hipster rep seem to be pinning it up there.

Though cagey about its location—license plates announce only “The Industrial State” or “The Highway State”—much of Ghost Dog was shot in Jersey City, where the boarded-up storefronts and decomposing car lots frame a character as obsolete as his surroundings.

One could never mistake Jarmusch’s films as explicitly political. The auteur is simply too wrapped up in the fascination he attempts to examine: even these two films are riddled with otherness.

Jarmusch sets it straight from the very beginning: Dead Man is a western precisely because it is not. The film positions itself against the ideological and formal constructions of the genre.

Jarmusch’s film, with its cheap stock characters, seems flimsy and incoherent, merely a one-off opportunity to combine disparate groups of actors of some international renown and see what happens.

The title card reads, “A Jim Jarmusch Film,” but by not examining the bandleader in any substantive way, Jarmusch concedes a certain measure of power.

Mystery Train is concerned with the rise after the fall, focused on those scraping and struggling not for greatness or fame but merely the ability to function, to relate, to survive.

The teenaged cousin of a French friend said he loved Down by Law because it was thoroughly American, alive with freedom and movement. France was closed, he said; the U.S. and Jarmusch, wide open.

Stranger Than Paradise, Jarmusch’s first feature film, still remains his best not because the man behind it was still, at the time of the film’s production, untainted and wide-eyed, but because the times themselves called for an American filmmaker like Jarmusch.

Jarmusch’s little-screened collegiate 77-minute debut feature, Permanent Vacation, is another movie wrapped up in cool, but the humor and circumspection marking those later films is absent.