The Name Above the Title

Eric Hynes on Year of the Horse

“You know what bugs me? It’s this guy, this new guy, Jim. He’s comin’ in here, thinks he gonna lob us a couple of cute questions and sum up 30 years of total insanity, of us trying to make music and be humans and have families and live through all our problems and differences and everything else. And how can he do that with two little questions? It’s gonna be some cutesy stuff like you’d use in some artsy film and make everybody think he’s cool. It’s not gonna capture anything. No matter how or what he asks, he’ll never get it all.” —Frank “Poncho” Sampredro, guitarist, Neil Young & Crazy Horse

In the three years leading up to Year of the Horse—Jim Jarmusch’s travelogue and concert film of Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s 1996 world tour—Neil Young had recorded and released four separate studio albums, two with Crazy Horse and two without. A ratio of more than one album per year was actually close to his career average—his persistent and prolonged productivity remains virtually unrivaled in the history of rock music—but he was entering his fifties, an age when his contemporaries had either slowed or faded completely, and he was peaking. All four albums were well received, and Young’s profile—which had fluctuated wildly over his 30-year career—was as high as it had ever been.

In January of 1993, during the heyday of the Seattle music scene, Rolling Stone put Young on its cover with the headline “True Grunge,” helping to foster a prolonged and occasionally published debate about whether or not he was the “Godfather” of “grunge,” which, in a nice reverse, made him a benefactor of the fad. His two subsequent albums, Sleeps with Angels and Mirrorball, were considered—and to a certain extent, made—in light of this turn in popular music. The former was recorded with Crazy Horse and was reviewed, due to the titular lament, as a response to Kurt Cobain’s suicide; for the latter, Young was backed by arguably the hottest band in the world, Pearl Jam. Less than a year later he released his score to Jarmusch’s Dead Man, and soon thereafter came another Crazy Horse record, Broken Arrow. In short, Young’s superlative output combined with his sudden alignment with a younger generation of stars, made him a good, though not particularly bold, subject for documentary study. The boldness came—with Jarmusch holding true to Young’s own deflective dynamism and artful self-destructiveness—in deciding to make the film about the band, not the man. It provides the film with a thoroughgoing tension to match its subject: the more times the mates refer to the band, the team, or the collective, the more we—and they—are drawn to the big floppy-haired elephant in the corner.

After a brief parking-lot testimony from a fast-talking German fan, the film begins with a mug-shot roll call of Crazy Horse: Ralph Molina, “drummer, vocals”; Frank “Poncho” Sampredro, “guitar player, comedian,”; Billy Talbot, “I’m the bass player in the band known as Neil Young & Crazy Horse”; and Neil Young, “I’m the guitar player in the band Crazy Horse.” What we’re witnessing, in a suitably self-conscious direct camera-address, is the presentation—and creation—of character. Whether or not they’re being or playing themselves, these introductions provide a convenient shorthand to the otherwise unwieldy subject on display. Sampredro acknowledges his extra-curricular role, Molina identifies his secondary vocal contribution, and Talbot’s accurate and subsuming identification is immediately contrasted by Young’s refusal to mention his own name as part of the band name (not to mention his un-Molina-like dropping of his more primary vocal contribution). But Young’s address serves an even greater function—it establishes Crazy Horse as the subject of the film, making himself a participant in the foursome rather than leader, and, most importantly, foreclosing discussion or examination of any aspect of Neil Young & Crazy Horse that falls afield of this egalitarian context. So no talk of songwriting (clearly Young’s domain), or of recording and production, and only elliptical references to Young’s long and steady legacy of work outside of Crazy Horse. The band as special, and familial, and enduring, are the talking points, and it’s unclear whether Jarmusch’s access to the band was dependent on his taking this approach (either instructed or intuited), or if he happened to share Young’s desire to celebrate the band. Since his access was granted during a tour, a focus on bandmate interaction and stage performance is kind of inevitable. But it’s impossible not to feel an imbalance between stage footage, in which Young is clearly the center of attention, and the interview and on-the-fly footage, in which he’s marginal. When, towards the end of the film, one member of Crazy Horse acknowledges Young’s leading role (which Young continues to refute), a truer sense of the band’s dynamic begins to emerge.

Since Frank Sampredro—called “the new guy” for having replaced deceased guitarist Danny Whitten 24 years prior—is the jester-in-residence, it’s appropriate that he alone pulls back the curtain, if only for a moment. After his mates, along with the band’s manager and Young’s father, attest to the “group thing”—the communal authorship of the band’s sound and energy—Sampredro says that unlike when Young plays with other people and gets to be himself and make his music, “With us he has to have a certain amount of extra energy to pull us all up as well. And so it’s tough on him...to play in Crazy Horse.” Sampredro is clearly proud of the music he makes with Crazy Horse, and onstage he and Young are twisted mirrors of autistic energy, but he’s the only one willing to suggest on camera that Neil Young’s name might belong in front of Crazy Horse. When Young follows Sampredro by saying that he always winces when he hears the full name of the band, his modesty comes off as self-denying at best, and hollow at worst.

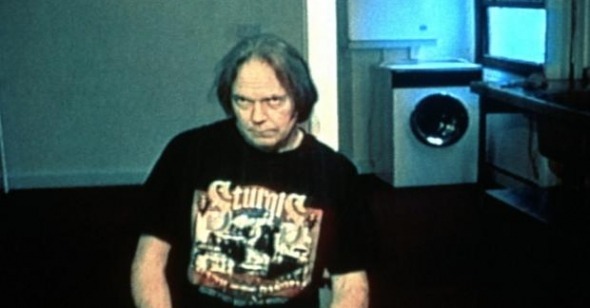

The Sampredro quote that leads this article is taken from a scene about halfway through the film. Sampredro, wearing large dark sunglasses and sitting in his hotel room, addresses someone off-screen, and it’s implied that Jarmusch is behind the camera. He gives a similar speech on two other occasions—once towards the beginning of the film and again right before the final live performance. By the third time, his laughter reveals that he’s at least partly kidding, and that his razzing of Jarmusch is limned with macho affection, if not prompted posturing. (Jarmusch finally responds, after Sampredro mistakenly identifies him as an “artsy fartsy film producer,” with what turns out the be the final spoken line of the film: “I don’t recall this in the script.”) But there’s irrefutable truth in what Sampredro says, and the film’s inclusion and repetition of his mistrust belies an awareness, perhaps even an admission of guilt, on the part of the filmmaker. In the end, Jarmusch doesn’t try to “get it all,” or “sum up 30 years of insanity.” He simply goes with the flow. Other than brief, sketchy oral histories of the band’s formation, the deaths of Whitten and producer David Briggs, little historical ground is covered, and no mention is made of personal lives or families, or of particular conflicts or bonds between members. Jarmusch keeps the scope limited to The Horse, and to the “energy” they share on and back stage. Somewhat like Young, his strategy is to blend in with the group, though Sampredro’s soliloquies show how tricky that can be. He, in fact, doesn’t belong. It illuminates a rarely admitted fact of fly-on-the-wall documentary, which is that camera and filmmaker are present by permission and at the pleasure of the subject. His concert footage, culled from two shows in two locations (Vienne, France, and The Gorge, Washington), successfully captures and evokes—from a predominantly fan’s-eye-view—the band’s frighteningly focused commitment to their singularly beautiful noise. His on-the-fly footage and Errol Morris-style interviews are a more problematic score.

Shot on Super 8 and 16mm film as well as Hi-8 video, Year of the Horse boasts a low-fi look to match the snap crackle crunch of the music (not to mention a fuzzy, flattened, color-bled aesthetic to further blend four into one). There’s no apparent scheme to the employment of formats, which fosters a sense of incidental immediacy. Concert recordings are fractured between color and b/w, sharp-focus and blur, and high and low exposure, so the sound remains constant, crisp, and loud, while the picture is ever changing and surprising. Also thrown into the mix are older film and video recordings made by Young and the band from the years 1976 and 1986, so that Jarmusch’s footage operates both on its own and as the latest installment in a career-spanning documentary project. Beyond giving viewers a sense of how long Crazy Horse has been playing (and laughing and fighting and smoking) together, this footage also speaks to the seriousness with which Young and the band take filmed documentation. In the 1976 footage, mostly shot on black-and-white film, their ease with the camera evokes classic cinema verité, and one 1986 clip involves a band meeting recorded by two mirrored video cameras mounted in the back of a tour bus. When Talbot claims to have not called for the meeting, Young laughs at his lie and says, “We’ve got it on tape.”

The truth is that Neil Young is a filmmaker in his own right. Besides purportedly possessing thousands of hours of private and concert footage of himself and Crazy Horse, he also directed the Neil Young & Crazy Horse concert film Rust Never Sleeps, as well as three other features under the pseudonym Bernard Shakey (listed as executive producer of Year of the Horse). Those three films—Journey Through the Past, Human Highway, and Greendale—all explore, to a certain extent, Neil Young as both documentary subject and fictional character. (In Human Highway, when Young’s bumbling—and tone deaf— gas station hick is knocked unconscious, he dreams that he’s a Young-like rock star that proceeds to jam with Devo in an absurdly transcendent reworking of “Hey Hey, My My.”) It’s reasonable to surmise that Jarmusch’s access speaks not only of engendered trust—earned through friendship or from an aesthetic affinity forged during the recording of the uniquely essential and colossally effective Dead Man score, or both—but also of a willingness to subsume his own ideas and designs within a Bernard Shakey production. The title card reads, “A Jim Jarmusch Film,” but by not examining the bandleader in any substantive way, Jarmusch concedes a certain measure of power. Whether he does so to maintain Young’s trust or to collaborate on a mutually intriguing group project (appropriate for the “group” subject), I can’t begin to say. But Jarmusch and Young appear together onscreen only once in Year of the Horse, long after the other three members of the band have had a more than their share of screen time, and it’s an illuminating, if curious, scene.

Jarmusch and Young are sitting left and right on a tour bus, Jarmusch in black but for his trademark shocked-white hair, and Young in typically bedraggled Eddie Bauer wear. Both are wearing sunglasses. Jarmusch reads from the Bible and Young leans in, listening intently. Young claims to have never read the Bible and asks the difference between the Old and New Testaments. Jarmusch explains that Old is before Christ, and that its God is a vengeful one. Young wonders if he’s vengeful because he made man, and man turned out to be man. He says it reminds him of when he planted trees only to cut them down when they turned out differently than he’d hoped. Jarmusch says, “Who do you think you are, God?” And Young says, “Yeah, right.” Only at this moment does bassist Billy Talbot come into view in the back row of the van, laughing. As the only scene that features both men together (Jarmusch is an otherwise inquiring voice or fleeting vision), it makes for an exciting digression. Firstly, because their likely farcical encounter is quite funny. But more importantly, because they are stars. Much like Jarmusch’s riffingly staged duets in Coffee and Cigarettes, the fun lies in watching two celebrities talk about non-celebrity-related things and making fictions of themselves in the process. Precisely because the scene is so fleeting, in an otherwise thoroughly even and respectful documentary of a group entity, it feels boldfaced. It’s as if, after all that restraint, they let themselves share the spotlight for a moment. It’s also telling that neither Jarmusch nor Young appear side-by-side in the film with anyone but each other—the balance of power briefly displayed. Co-conspirators, and perhaps co-directors, both are leaders, auteurs—the primary creative force in their collaborative fields. They both like the idea of teamwork and succeed in making wonderful art with others and even each other, but when all is said and done, whether they cop to it or not, they still like seeing their names before the title.

![]()