See It Big

Articles written on films showing in the Museum of the Moving Image's SEE IT BIG series, co-programmed by Reverse Shot editors Michael Koresky and Jeff Reichert

Rivette’s ordination of Journey to Italy as the first modern film is, in a philosophical sense, paradoxical, because in fact it is modernity itself which is being shunned, or at best broken down and humanized, by the film.

Bigger Than Life is a film filled with contradictions, paradoxes and confusions of emotion and reason; indeed, these are part of what makes it big and ugly and beautiful as life, even in its outsized proportions.

How massive the landscapes and castle chambers are in Akira Kurosawa’s 1985 epic, and how small the people in them seem.

Fanny and Alexander is a celebration of the act of looking, in all its power to invent, animate, and destroy; it goes so far as to suggest that the things seen owe their qualities, their presence, even their existence to the seer.

The world in Suspiria is so threatening and unstable that colors glow with sinister intensity, the camera moves as if possessed, and natural sounds abruptly give way to jangly music—and that’s just the first minute or so.

Death is here something to be profoundly feared, something that can’t be quantified; the ghostly realm exists not as a concept but as a reality and an end point.

The Thing is not just an unnerving title: by its nature, the enemy, a corrosive alien organism which kills and replicates its prey, has no distinct face or personality of its own—a “conquer and survive” motivation is initially ascribed to it, but it defies any description.

What if the old saying “You can’t go home again” has it backwards? What if we’re invisibly bar-coded to our point of origin, and we’re just spinning our wheels on the map when we try to leave, failing to shed the place we came from?

The way in which Lynch handles that severed ear offers a crucial hint as to how Blue Velvet simultaneously establishes these parallel worlds and destabilizes the boundaries between them.

A “free adaptation” of Petronius’s fragmented-by-the-ravages-of-time, first-century mock epic, Federico Fellini’s Satyricon (1969) is filled with constant, unexpected laughter.

One of the many remarkable things about Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo is the way it lulls you into believing you’re just watching an ordinary western. For an unlucky few, this sensation might even remain intact right until the end, but chances are that something in the film will break the spell.

The famed first sequence of Apocalypse Now not only lays the hallucinatory groundwork for the rest of the film, but it also foregrounds the very scale of the destruction wrought during the Vietnam war.

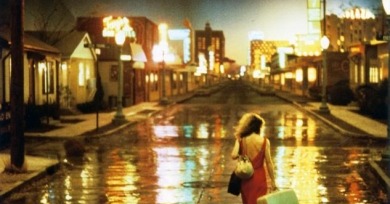

During his career heyday, thinking small wasn’t part of Coppola’s vocabulary, and One from the Heart easily ranks on any list of filmmaking egotism gone amok.