At the Museum

Goings-on at Museum of the Moving Image

The setup of the film works less as narrative than as an inception point for numerous complementary and competing layers of fiction and reality, including the test footage for the film-within-a-film, scenes relating to its production, and footage of life in Tokyo.

Just as Jay takes his place as the figurehead of a pagan cult, so too did Kill List crown Wheatley as the king of UK horror movies when it was released theatrically, a speedy ascension to a throne that had sat vacant since the 1970s.

In this Reverse Shot Talkie, director Joe Frank and host Eric Hynes browse the aisles of R.A.O. Video in Little Rock, Arkansas, to discuss the unique origins and process for his debut film, Sweaty Betty.

With naked bodies slowly twisting and writhing in a thick, inky chiaroscuro, a hazy but unidirectional light giving definition only to the rounded forms and flexing musculature of the women onscreen, it is clear that Grandrieux has painting on his mind.

Kämmerer has, over ten years and as many films, established himself as one of Europe’s most exciting and formally economic young filmmakers.

"The film is never going to be transferred to digital. It always has to be shown as film, and it was constructed as a palindrome, so it could be shown from either end, and you can’t really do that with digital."

This mournful film takes the utopian aspiration of Communist dreams seriously, without overlooking the dangerous faults at their core.

"All the shots in my films are always the same, but they are different from one film to the other. In this film I did not want it to be too long. They are about fifteen seconds. It is the minimum. I cannot make this film with shots of less than fifteen seconds."

Often the idea of the avant-garde implies a somewhat detached, contemplative mode of viewing, and this aesthetic stance is kilometers away from Gagnon’s bailiwick. Of the North seems to invite rubbernecking more than any conventional audienceship.

This elegiac essay-portrait is unexpectedly timely; it concerns Portuguese cinema and its uncanny position between life and death, past and future. Its subject is a legendary film scholar, programmer, and longtime head of Cinemateca Portuguesa.

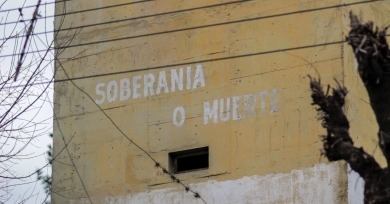

“I am not a political commentator. But as an artist, I feel that the authorities must allow dissent. There has to be a space for protest in society. There has to be freedom of expressing our disapproval of the state of things as well. This right cannot be taken away from the people.”

Pialat’s quest was to seek out something more artistically valuable and emotionally direct: a cinema of genuine immediacy and truth, a cinema from which fragments of real life could erupt from the screen, where moments could simply exist, freed from the yoke of their context or origins.

The wide-gauge format reached its greatest popularity in the 1950s amid a boom of new innovations intended to reverse the fortunes of foundering Hollywood studios; for a time, they even appeared to have done the trick. But every great reign is followed by an epoch of decadence . . .

A visual poet with a penchant for knockabout brawling, an idealist who gravitated to tales of melancholic loss, a notorious tyrant who cultivated long friendships, a nineteenth-century sensibility revered by many a hardcore modernist: John Ford, as they say, contained multitudes.