Reviews

In a moment when documentary film seems back under the thrall of all things cinema vérité, How to Smell a Rose is a terrific reminder that vérité is not merely the avoidance of interviewing subjects on camera, the eschewal of tripods and lighting, or acting the proverbial “fly on the wall.”

Were these poses merely all part of a larger, calculated performance Marlon gave in service of the role of his lifetime: that of “Brando”?

Phoenix is a gorgeously odd film, a quietly symphonic elegy fueled by a magnificently preposterous plot that ends up as something like a cross between Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli and Hitchcock’s Vertigo—but communicated through the specific experience of Jewish-German identity.

All plot synopses are necessarily attenuations, but for Horse Money any summary feels especially futile, or even violent, a crude reduction of its complex network of impossible geographies, fuzzy memories, and jumbled chronologies.

Woody Allen’s latest, Irrational Man, is, whether one accepts or rejects its brutal fatalism, a totalizing aesthetic experience that provides evidence that this seventy-nine-year-old is a craftsman we should still be paying attention to.

As with Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, another masterpiece dedicated to present-day witnessing, to chasing the ghosts of atrocity across the living landscape of our ruined humanity, it’s important not to overlook the extraordinary artistry that allows for such extra-cinematic effects.

Sean Baker makes widescreen movies. Not only in the sense that he employs a rectangular aspect ratio, but also by seeking to include as many characters as possible within the physical area of a shot.

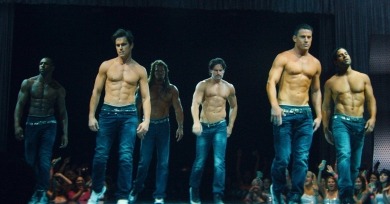

Magic Mike XXL is able to express something about catering to fantasy life with such clarity because it deals with the business of female fantasy—or, rather, the prepackaged version of female fantasy filtered through available cultural signs and symbols and enacted in the arena of the strip club.

In trying to figure out how The Princess of France can be as phenomenally accomplished as Viola while also a bit less immediately appealing, it may be best to defer to the Bard: the play’s the thing.

Whether a child will grasp this all enough for it to resonate is questionable, but adults are invited to reflect on their own lives, likely filled with crumbled islands, doors once open, shut, often cruelly, in our faces by fate, luck, our own weakness or inability. Life, suggests Inside Out, is destined to include disappointment.

Like Olivier Assayas in Something in the Air, Hansen-Love is smart enough to show that adolescent collectives are at least as much about the rush of experiencing something—be it a rave or a protest rally—in close physical proximity to one’s peers as the thing itself.

What rankles about The Tribe is that its trick (removing spoken language) is only clever enough to cover Slaboshpitsky’s vague faculty with his narrative elements for so long. It’s also a plodding, often crushingly boring watch.

For many of us, at some point in our upbringing, the movies variously played the part of babysitter, behavioral role model, playground inspiration, and substitute parent. For the six Angulo Brothers of the Lower East Side, stars of The Wolfpack, you might say that the movies were very nearly everything.

Each of these set pieces is superbly executed within Andersson’s trademark long-take style, and the dichotomies they set up—between past and present, reality and fantasy, and comedy and melancholy—are potent and suggestive. They are all also basically copies of scenes that the director has done before.