Reviews

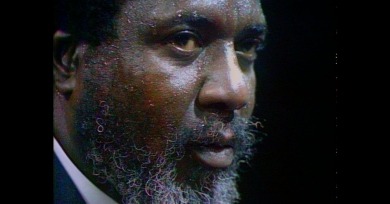

What Alain Gomis has uncovered in these rushes is fascinating, proof of the confines of bourgeois culture an artist such as Thelonious Monk was forced to endure in his time.

A stunning feat of oral history, interweaving the lucid and at times jaw-dropping testimony of a multitude of eyewitnesses and participants with extensive and eye-opening newsreel footage from French, German, and British archives.

Tatum can market himself as a figurehead for a mainstream, sex-work-adjacent live show in part because he is now, primarily, a movie star in the public consciousness. The character of Mike, on the other hand, is a nobody in a foreign country.

Like many an adoption drama, Return to Seoul does trace a search for personal identity. But the film is unusual in the degree to which its transformations conform to those of its protagonist, matching her changeability with its own destabilizing structural reinventions.

The film has been constructed in a way that puts the dual onuses of perception and interpretation onto the audience. It is a heavy burden that is also hard to process when you’re being slammed around so forcefully.

Full Time is largely about the labor that continues in the shadows of a labor strike, and the non-union workers living outside Paris whose lives are overturned when the city shuts down. Julie is not a Norma Rae-esque heroine interested in organizing for the greater good; she is just trying to keep herself and her family afloat.

Andrew, Eric, and Wen, held hostage in their lakeside cabin rental, are told by the invaders that they must make a decision to sacrifice one of their family members to save everyone else in the world, inverting the usual extremist take. Time is running out, tensions are running high, and all we can do is watch.

Brandon Cronenberg tends to confine transformation to the imaginary realm. For him, the body is but a plaything of the mind. This has produced some striking visuals, but they fail to linger, couched somewhat safely in their unreality.

The strange cross-section of eras and technologies becomes its own kind of visual rhetoric of alienation; the crushed blacks and embellished film grain abstract even the most rudimentary shots of hallways and open doorframes into the shapes a child might imagine as those of monsters.

I cannot imagine seeing something more compositionally thought-through and artfully constructed in the current cinema, or something that more compellingly refuses to divulge its secrets while also maintaining a constant engagement with so many legible ideas.

The film is bolstered chiefly by the cast of nonprofessional actors, who together form an entirely authentic unit, feeding off one another’s energy for better or worse.

For most of its running time, Babylon barrels past any possibility of wistful reverie, content to wallow in excess and sin, only to devolve in its final third into meditations on the power and beauty of the image.

Try as Kore-eda might, the questions the film raises cannot be fenced off from the global fight for reproductive justice, a battle from which this politically evasive film has been totally sequestered.

His latest thoughtful docu-fiction hybrid, No Bears, is deceptively gentle, initially even comedic, lulling with a ruminative pastoral quality that is gradually pierced by painful reminders that these are more than stories—they are the contours of people’s lives.