Nick Pinkerton

In contemporary Hollywood product, shopworn words like “honor” and “loyalty” turn up as frequently as “freedom” and “liberty” in a George W. Bush campaign speech, and with similar impact.

“The American Problem,” so-called, has undeniably been the Cannes-defining cog around which the hot-button cinema of the past two-plus years has rotated.

Though lacking the fantastic flourish of, say, a King Ghidorah or a Megalon, there’s something perfect, almost classical, in the form of Godzilla.

Written, directed, produced, lit, shot, and edited by Ceylan, it easily lends itself to auteur association, and its disengaged, articulate imagery, spread across unhurried takes, has the sheen of willful artistry.

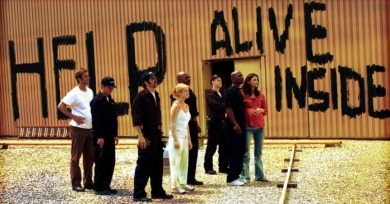

Horror cultists, willfully clandestine and fiercely territorial, will doubtless be appalled by this latest multiplex spin-off of George A. Romero’s Dead series, something of a sacred text for the gorehound crowd.

Our proximity to Delphine’s crisis is deepened as the film’s claustrophobic universe rotates tight around her steady sadness, mirroring the way that depression’s folded-in egoism realigns the world in reference to one’s own irrepressible lack.

What’s astonishing is that the cockeyed combination of Potter’s moral wariness and Ross’s earnest showmanship, for every botched dialogue, twice as often stumbles into the sublime.

The film is an elementally emotional work, flooded everywhere by a deep, regretful sort of fatalism.

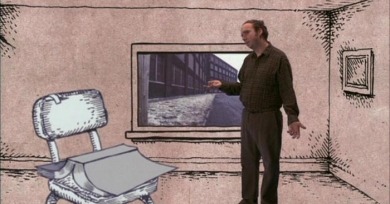

This all goes back to American Splendor’s simplistic formula for the presentation of reality and unsentimental truth: take traditional “Hollywood bullshit” values and flip-flop them with pancake precision, as in Joyce and Harvey’s first date, an absolute catalogue of a-romantic catastrophe.

The movie can’t seem to relax and forget that it is Ozon’s portrait of the artist as a middle-aged female detective novelist; suffice to say that the book that Sarah Morton finally produces in the aftermath of her vacation is our movie, Swimming Pool.

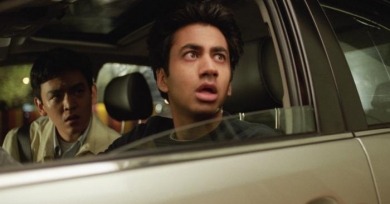

Russell’s film, the story of a clandestine U.S. military detachment going after misappropriated Kuwaiti gold and winding up in a taboo alliance with anti-Saddam rebels, is now half a decade old, and it would certainly seem to beg revisitation and reconsideration in light of contemporary events.

In Hollywood, where profit margins are worked through to the tenth decimal before any celluloid gets to be exposed, and where every incoming product proudly wears its demographic on its sleeve, the appearance of a big-budget born loser like Willard is anomaly enough to make anyone take notice.