The American All-Stars

We asked our writers to pick a contemporary filmmaker from a Latin American country who they’d like to champion; this could trigger a longer discussion about an oeuvre or an idea on a national cinema, or it could remain a close reading of a film itself.

His films refuse the documentary classification by insisting on including fictional elements, and reject the narrative categorization by dropping hints concerning character and story only obliquely.

This exceedingly strange bundle of nested narratives dared to introduce scores of characters and storylines (some rich tributaries, others dead ends), perspectives and locales (Mozambique-for-India, the Salado River) with an almost ceaseless stream of omniscient voiceovers.

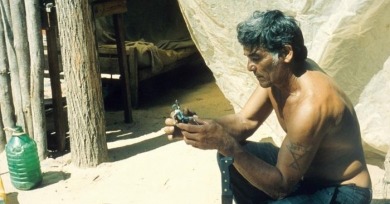

At an unflagging pace and a bracing sensorial intimacy, each of Polgovsky’s documentaries exploits the paradox of HD video: its mobility and immediacy and its seemingly endless plasticity.

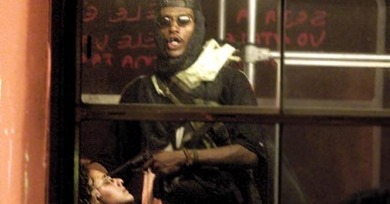

It remains tethered to noir and thriller conventions, but more intently commits to probing character psychology and, with narrative obfuscations, stubborn silences, and stylistic mood swings, venturing outside assumed viewer comfort zones.

The 1989 short Isle of Flowers, a social critique about poverty in contemporary Brazil, is a direct descendant of the Cinema do Lixo movement, directed by renowned director Jorge Furtado, who remains a popular filmmaker to this day, touching upon social issues in documentary, fiction feature, and TV work.

Like all of his films, it’s a work of major excavation, only in some ways more literal: setting the groundwork for the film’s many narrative and philosophical threads is its portrait of the Atacama desert, its past and present, its sky and earth, its technological and historical resonances.

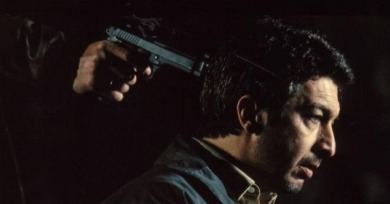

Who is José Padilha: clear-eyed chronicler of society’s forgotten souls, or misanthropic peddler of pummeling law-and-order fantasies? It’s a question implicit in the critical reactions to Elite Squad (2007), the Brazilian director’s fictional follow-up to his 2002 documentary debut, Bus 174.

The two low-key films Rebella and Stoll made together exist in largely anonymous urban spaces; even though the pair has been touted as leaders of new Uruguayan cinema (a notion which Stoll rejects), their films feel almost as if they could have been made anywhere—but this isn’t a criticism.

She possesses a rare and unsettling talent; her movies are at once confounding and, in their way, perfectly intelligible. Already, she has staked a claim as a major film artist with a small but astonishing oeuvre that demonstrates a preternatural command of the medium.

Federico Veiroj’s pint-sized second feature, A Useful Life, runs only slightly over an hour, but the gauntlet it tosses at the feet of the cinephiles who are its most likely audience suggests a young filmmaker eager to grapple with the state of film culture.

Not only does he acknowledge gay men’s longing and desire, he makes it explicit by eroticizing both their gaze and ours—statuesque, youthful, darker-skinned bodies moving alluringly through time and space.

Though she made her feature filmmaking debut with Mutum (which closed Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight program in 2007 and toured as part of 2009’s Global Lens initiative), Sandra Kogut has been an active documentarian for the past two decades.