The Killing Floor

Benjamin Mercer on Lisandro Alonso’s Los muertos

What do we know about Vargas, the main character of Argentinean filmmaker Lisandro Alonso’s second feature, Los Muertos? About as much as we know about the protagonists of Alonso’s two other features—2001’s La Libertad and 2008’s Liverpool (Fantasma, an hour-long 2006 film set in a Buenos Aires movie house, rounds out the director’s body of work)—which is not a lot: that he is from a remote part of Argentina, that he is a man of very few words, and that he has grown accustomed to an all-consuming daily routine, in the graying Vargas’s case a long incarceration for the murder of his two brothers. In all of Alonso’s films—which look at the lives of the rural poor, often observing non-actors in long, contemplative takes as they approximate for the camera their everyday labor against scenic but vaguely threatening natural backdrops—the director takes a quietly defiant stance against cinematic conventions. The only label the thirty-five-year-old filmmaker doesn’t apparently shirk is that of “Argentinean”; the director’s committing to film of some of the country’s most remote and forbidding locations, for the most part far from bustling Buenos Aires and its most basic amenities, practically constitutes a national project at this point. Otherwise, Alonso’s films are meditative but thoroughly unsettled: his films refuse the documentary classification by insisting on including fictional elements, and reject the narrative categorization by dropping hints concerning character and story only obliquely.

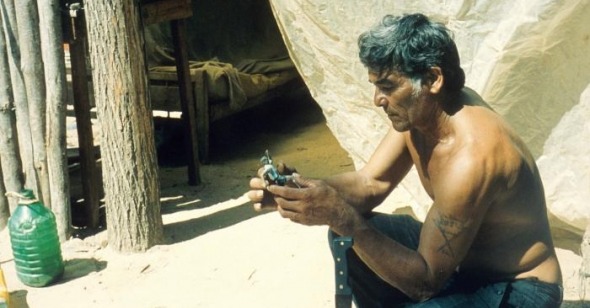

So we gradually learn during Los muertos’s opening chapter that Vargas has been imprisoned and why, but any other significant information about him, particularly regarding his interiority, is less readily discernible. At the beginning of the film he’s in the last days of his sentence in a rural jail, where inmates are more likely to share maté than menace each other. The prison has a morning roll call and established sign-out procedures, but it’s not punishingly institutional in any traditional sense, with an overgrown, sun-dappled yard and what seems like a rather leisurely work routine. Vargas appears less at ease once he’s freed from the place, though he feels the pull of family, setting out immediately to visit his daughter. Before his trip, he spends most of his savings at one provisions outpost, buying her a green blouse, the only gesture Vargas makes in the film that suggests anything like tenderness. (For point of reference, direct lines of inquiry about his inner life in the film go nowhere; when a boatman later asks about Vargas’s brothers, Vargas claims to have forgotten the whole horrific episode.) Like the woodcutter Misael, who inquires eagerly after his mother over a payphone in La Libertad, and the sailor Farrel, who treks over the Patagonian tundra to check in on his mother and daughter in Liverpool, Vargas contemplates his separation from his own family, and attempts, however feebly, to atone for it. These are hardened men resolutely on their own, but we know they have at least considered the alternative of family togetherness.

But Los muertos is the most radical of Alonso’s features because of the nature of what we don’t know about the protagonist: namely, whether or not he is a serial killer. The film begins with a prologue that hangs the specter of death over the rest of the film. During this brief sequence, shot in disturbingly calm whorls (this is perhaps the most conventionally stylized sequence in Alonso’s oeuvre), we glimpse two corpses lying face down on the jungle floor, and a blade-wielding figure flitting by. Later, we see Vargas slay a goat with a machete, slitting its throat and letting its blood cascade onto the floor of his boat. To survive in the kind of jungle terrain that Vargas traverses, surely you must be able to slaughter a marooned and seemingly helpless animal without pause, but there is something off-putting about the efficiency with which he removes its innards and scrubs down the emptied inside of its body. Tellingly, we do not see him cooking or eating the goat, as we see Misael do with an armadillo at the end of La Libertad.

So we have only these instances of violence to suggest a way of filling in two troubling blanks in the last third of the film, elliptical domestic scenes through which Vargas ominously drifts. On his way to his daughter’s, Vargas stops at the dwelling of a woman named Maria, the wife of a former fellow inmate, to whom he delivers a letter. She also has a son, Angel, a carpenter. Vargas dines with them and stays the night, emerging from their house in the morning by himself, washing his face, hands, and hair, and without any sort of farewell making haste to his boat. Alonso then cuts to him by the river, cleaning his machete. At the end of the film, when Vargas, goat carcass in hand, finally reaches his daughter’s residence—only to find that she is not there, having left her son in charge of his younger sister—Vargas enters the tent where his grandson and granddaughter take shelter. He brings his machete in and lays it down. The camera wanders off, focusing eventually on a plastic toy on the ground outside the tent; chickens pace back and forth. There is a noise that sounds like the machete being picked up before an unsettling, though none too loud, ripping sound.

Whether Vargas is a cold-blooded killer terminating those he visits with extreme prejudice, or whether something altogether more benign is going on here, is a question that Alonso is all too happy to leave unanswered. After all, one suspects the minimalist, ever eager to play with audience expectations (the opening credits to the glacially paced La Libertad and Liverpool both feature incongruously uptempo music), enjoys structuring the narrative of Los muertos as a linear horror film of gathering suspense, but one which at every turn refuses to acknowledge the horror, looking away when violence might rear its head. This is not a film that recoils at any suggestion of bloodshed—as the prologue and the goat-slaughtering sequence attest. Violence is not beside the point, then. It is Alonso’s suggestion, rather, that it is immaterial whether Vargas remains a killer after his incarceration; despite its initial prison-film trappings, this is emphatically not a film about recidivism—this seems a foregone conclusion for Alonso’s other protagonists, who yearn to change, yet don’t appear capable of it—but about the dominion of the landscape.

Alonso’s films are never so much about what as where—severe settings that condition their inhabitants to adhere to strict routines, to constantly keep in motion performing their lonely work, resigned to the likelihood that if they rest for too long their surroundings will engulf them once and for all. These places often open up space for contemplation only to rapidly colonize it, both for the characters traveling through them and the audience watching—in the case of Los muertos, in which the camera lingers over lush greens, the viewer’s mind wanders before coming back around and registering how hypnotically (and terrifyingly) lush the flora is. Alonso often drifts away from his protagonist to gaze on the environs. When Vargas gets off the back of a truck, the camera stays on, keeping track of him in the receding distance until he is no longer visible, at which point the camera pans up to the tops of the trees and the sky; later, the camera strays from him while he’s rowing downriver, drawing attention to the thick of the jungle on either side—but it never feels as if the film’s focus has shifted in these moments. Vargas is always adapting to the environment, so in that sense he seems to become a sort of mirror image of it.

The same could be said of Farrel, the sailor in Liverpool, who uses his leave to undertake a long journey home. He is often captured tramping through the icy expanse of Tierra del Fuego in long shot, as if he is making no impression on the icy environment, that it’s entirely indifferent to him, and that this is, at least in part, the source of his restlessness and anxiety (the contents of his gym bag include a bottle of vodka from which he takes generous swigs). At one point in Los muertos Vargas is guided by a boy who wields his own machete, hacking away just to clear a path through the trees in front of him. It’s one reminder among many that you must constantly push back against the jungle if you want to survive in it—even more than you would in a tundra like Liverpool’s because a jungle is constantly growing. Though Vargas doesn’t betray any obvious form of panic, his trip through the jungle might easily be described in a series of increasingly desperate defensive actions: walking, paddling, pulling, swatting, slashing.

Los muertos is an open-ended horror film about an environment where violence is part and parcel of daily life—or where a man might simply be forced to kill his brothers to save them from the terminal agonies of starvation (the original motive in the Los muertos script, according to the critic James Quandt’s thorough Artforum survey of the director’s work). We don’t know much in the traditional sense about Alonso’s characters, but we learn, gradually, that their behavior is conditioned to a large extent by the severe Argentinean landscapes we see them moving through. Their worlds are beautiful but unforgiving places that can pare down their agency to the basic rigors of work and survival—the title La Libertad might as well conclude with a question mark—and, as Los muertos chillingly asserts, even turn killing into little more than a reflex.