Reviews

Though Godard’s latest nudge at the limits of cinema parades a number of the director’s usual puckish gestures, multilingual plays on words, and provocative image-puns, it’s nonetheless a dour archaeology of the roots of our cultural end times.

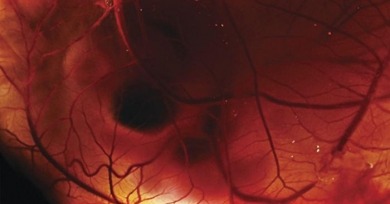

Though separated by over a century of cinema, L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat and The Tree of Life share a fundamental sense of wonder: at the image, at the world, at the fact that we are able to capture pieces of its beauty in images.

The Tree of Life is a movie of infinite moments, culled from one person’s singular experience and placed side-by-side in a free-floating mosaic.

After a first viewing of Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, the only response can be an ecstatic litany of the tiny, seemingly mundane moments that holistically create its world.

In 1944, toward the end of his life, D. W. Griffith lamented, “What’s missing from the movies nowadays is the beauty of the moving wind in the trees.” By then, the sound film had eclipsed the cinema the director had shaped in the early decades of the twentieth century.

The Tree of Life can be seen as an experiment in radical subjectivity: Malick doesn’t just show us Jack’s point-of-view; he immerses us within his conflict of spirit—through his kaleidoscopic and elliptical depiction of Jack’s early life, Malick retraces the moments of Jack’s spiritual and moral “becoming.”

None of Romanian filmmaker Radu Muntean’s films have yet seen commercial release in the U.S., but he’s one of his country’s most accomplished realists.

The surprise of Midnight in Paris is that Allen goes on to acknowledge that magic as a mirage. The charm of the film is that he does so while retaining that very magic. It’s a lovingly conceived and crafted bauble of a film, one of Allen’s one-note, high-concept fantasies.

The movie is less a laugh-desperate extended SNL skit than a very funny character study of a woman’s depression and her struggle to get herself back on track. We already knew Wiig could make us laugh, but we didn’t know she was a strong dramatic actress.

Those searching for fresh evidence that the collective obsession otherwise known as “the crisis of masculinity” remains alive and kicking: look no further than Hesher.

For viewers on the mainland, City of Life and Death is an unprecedented opportunity to see one of the most devastating episodes in the nation’s history elevated through a universalizing, readily exportable cinematic language.

Stripped of his powers and biding his time in a tiny New Mexico town that looks like it consists of one dusty block, Hemsworth turns out to be a real stand-up guy, charming as he smashes coffee mugs with pleasure and grunts to the waitress for more drink.

Taking a camera crew into the restricted recesses of Chauvet, the German director becomes docent to the damnedest gallery you’ve ever seen.

The “Delicious” of that grotesquely awkward title is Dean O’Dwyer, a paraplegic Angeleno living out of his car who DJs under the name Delicious D. Thornton, himself wheelchair-bound with a broken back, plays D as a mostly unlikable cauldron of resentment and self-pity. He has reasons to be surly.