Reviews

For Cone, queerness is less about the polemical assertion of identity than about recognizing the endless flux of experience and desire that renders labels and classifications at best arbitrary and at worst stultifying. It is a kind of queer humanism.

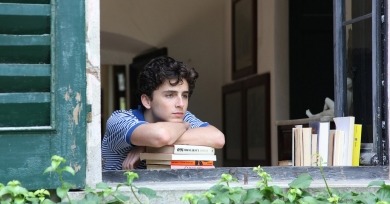

Guadagnino and screenwriter James Ivory have produced a film that simultaneously analyzes and dramatizes issues of sexuality, religious identity, and, once again, privilege and yet without straining against its clearly marked narrative boundaries.

Despite the infrastructure set in motion centuries ago to keep only whites in positions of power, Mudbound elegantly depicts how such ingrained racism only serves to aid whites in digging our own graves.

Three Billboards is the kind of momentary crowd-pleasing entertainment that will satiate audiences looking for the movie equivalent of a knee to the crotch—which not so incidentally is one of its defining images.

What has not changed, despite the shift into genre, is the commitment to helping us sympathize with damaged, alienating (and alienated) people. In his films we might feel the discomfort of self-recognition from these characters, while in all but the finest horror films, their predicament is usually reduced to a motive for a reign of bloody terror.

An occasional tin ear for old-guy dialogue suggests Linklater might still be more comfortable with the casual-philosophical badinage of those a decade or more his junior, but the 12-year gestation gives the film the distance crucial to its angry, sad, but, in hindsight, wise perspective on the early Iraq War years.

Gerwig evokes that specifically senior-year feeling of the rapid approach of adulthood through a swift editing style, offering a dynamic rhythm that conjures the sense of finite time she has with family and friends, a patchwork of energetic montages propelling Christine and the story forward.

In a film like The Work, with its multiple layers of privileged access and precariously obtained permissions from an array of potentially volatile participants, you are not just being allowed to see. Your sight is essential. Seeing and being seen is the point.

There is a nervous breakdown at its center, not necessarily by its protagonist but by the norms and institutions that sustain him. A lacerating critique of liberal cosmopolitanism, The Square is at once an art-house provocation of supreme calculation and a guttural sob for an unhappy West.

Robin Campillo himself was a participant in ACT UP-Paris in his younger days, and the easy jockeying between strategy and action in the film would likely have been near impossible without his insider perspective.

Here, queerness is not figured along the lines of sexual orientation or gender identity so much as the otherness that comes with being differently abled and, even more immediately, with a sense of loss.

A Gentle Creature is more of a destabilizing shock to the system than a call to arms, a confrontation with a broken state rather than a blueprint to rebuild it. It confirms Loznitsa as a master craftsman of the impeccably designed and crafted hellscape, politically charged and all-consuming.

Meyerowitz splits the tonal difference between his kinder Greta Gerwig collaborations (Frances Ha, Mistress America) and the more acerbic works surrounding those, dealing with the previously unlikely possibility of forgiveness and healing.

The disconnect between the liberated shooting and editing style and the social entrapment actually experienced by its characters gives The Florida Project its indeterminate feel and ungainly shape.