Michael Koresky

A film like Martin Rejtman’s Two Shots Fired—if there is another film like Two Shots Fired—encourages critics to talk about the radical power of narrative digression. This assumes, of course, that a film has a centralized narrative to begin with . . .

We talk a lot about how the camera moves through space, and the implications of those choices to move in or out or sideways, but it's rare that we just stop to consider the size and shape of the frame itself. And isn't this where every film starts?

Tsai Ming-liang’s movies may be spare and melancholy, but they make us feel anything but empty.

With the overall invigorating Clouds of Sils Maria, Assayas takes another curious glance across the ocean, and his film, more humane than demonlover (if not as purely emotional as Clean), continues the trend of making films about women that are equally about play-acting and performance.

While We’re Young traffics in a specific image of privileged urban whiteness, the kind in which materialism is seen as its opposite and liberalism is merely the fiction of all-inclusiveness.

As Manny Farber helpfully pointed out, “a film cannot exist outside of its spatial form.” But La Sapienza takes space as its literal subject, how the environments we build for ourselves, either architecturally or emotionally, create room for the known and the unknown.

There’s a central, important contradiction to the show, which is our ad-exec main character feels enormously, existentially detached from the materiality of everyday life—the very things, concepts, and ideas he is meant to be hawking (except, perhaps, for Hershey bars).

Mitchell and his cinematographer Michael Gioulakis do the concept justice with an unnerving aesthetic approach that makes the film’s timeless suburbia as much a character as any of the terrified kids who populate it. Imagine Sofia Coppola’s daydreamy The Virgin Suicides transformed into a twilit nightmare.

With the woman’s dainty toes center screen, the foregrounded width of the image, and the lovingly worn texture of the film itself, Death Proof is from its very first shot the ultimate Tarantino fetish film.

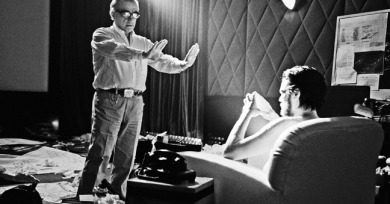

In honor of See It Big: Gordon Willis, the Museum of the Moving Image screening series co-curated by Reverse Shot, Michael Koresky and Jeff Reichert here pay homage to the great cinematographer by focusing specifically on his work in Woody Allen’s 1978 drama Interiors.

Kinky but never salacious, The Duke of Burgundy is a penetrating dissection of an imbalanced relationship before it shifts into being a surreal, teasingly nightmarish evocation of that imbalance, and it’s more fascinating as the former than the latter.

Reminiscent of Spielberg’s Lincoln in the way it limns the edges of its central great man by intensely focusing on practical matters—how, not just why, he forced and instituted political change—Selma is more procedural than biopic, although it doesn’t shy away from attempting nuanced, human portraiture.

The Babadook takes the form of a somewhat conventional bogeyman story, but it has much more on its mind. With this frightening, seemingly simple story of a children’s book monster come to fearsome life, Kent burrows into the mindscape of two people—a mother and son—contending with delayed post-trauma.

Bennett Miller’s bleakly efficient film is not only about America. It’s also about masculinity, brotherhood, fatherhood, class, competition, the drive for self-definition and expression. (It’s about just about everything except, of course, women, save one looming, destructive mother figure.)

A Few Great Pumpkins

Isle of the Dead, Twilight Zone: the Movie, Eyes Without a Face, Candyman, Night of the Demon, Black Sunday, The Babadook

By its nature, 3D only functions if the apparatus used to record its images and the human eyes there to receive those images all work in tandem. What happens, Goodbye to Language wonders, when even that breaks down, yet the pretense of 3D remains?

For such an icon, Scorsese is fairly tricky to pin down. What threads, if any, connect his various, distinctive films? Is he more fascinating a director because of commonalities between his films or divergences?

There’s nothing subtle about using a literal avalanche as a catalyst for the disruption of a seemingly perfect nuclear family, but it’s a lack of subtlety that’s surely not lost on director Ruben Östlund.

Thinking of The Heart Machine as a film about the split between the physical and the emotional, and the romantic difficulties that emerge from that, is more helpful than typifying it as another “relationship drama for the digital-age.”

The Aviator’s first act is so intensely experiential and bizarrely fast that it feels like we’re watching a civilization in freefall, a three-ring circus with Hughes as its reluctant master of ceremonies.