Eric Hynes

Bootleg DVDs are popular everywhere, but Russian bootlegging is unique in that it’s basically legitimate (legitimacy here being a very fluid term). Though it’s technically illegal to make them, it’s apparently legal to sell them.

If anyone tells you that Million Dollar Baby “isn’t really about boxing,” they’re doing a disservice to the film and overlooking its central achievement. It’s all about boxing every second, every frame.

Tsai Ming-liang works too subtly and too organically to lay it out for us, but with What Time Is It There? he explores every worthy connotation of the word departure, from taking a trip away to taking the final, mortal bow; from making a substantive personal change to simply saying goodbye.

Those that turned out to see The Right Stuff, ostensibly compelled by the sexless civics come-on, must have been very confused. Movies like this—an ambitious hybrid, a long, true-to-life space oddity—just weren’t made anymore.

The male protagonists in Alexander Payne's last three films are American counterparts to Chekhov's Vanya: melancholics desperate to slow a quickening slide. And like Chekhov, Payne eases his audience into the dark corners, summoning laughter that later gets caught in the throat.

Though its narrative precision has a way of making decisions feel predetermined, Maria Full of Grace benefits from these jarring transitions, its point-to-point speed deepening our sense of Maria’s impulsive character.

Finding an appropriate distance from Slacker is essential to acknowledging its achievement, which is due in part to Linklater’s own careful negotiation of distance from his characters and their ideas—which, more often than not, are elaborate arguments for distancing themselves from others.

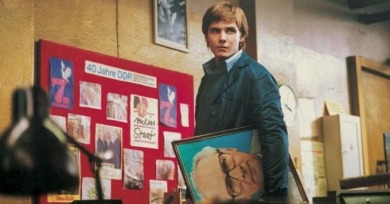

For a film that so fondly recalls Germany’s recent socialist past, Good Bye, Lenin! is awfully materialistic. As political as a pop tart, as full of product worship and as breezily incoherent as a VH1 retro special, writer-director Wolfgang Becker’s first stateside release is a valentine to East Berlin—western style.

Rather than comfort, his camera wants to unsettle, to set our limitations, to suggest more. Common are shots of near-microscopic closeness that pan to accumulate, and close-ups that pull away to reveal. To get at the heart of things, he never starts from without, but from within.

Like the absurdly giant fish that lumbers through the water in the opening sequence—a CGI creation meant to evoke a rubbery, low-tech effect—Tim Burton’s latest film, Big Fish, seems burdened by contrasting demands.