The Films in His Life

Nick Pinkerton on Goodbye, Dragon Inn

What is it about the movies that make this medium so prone to hysterical paeans to itself? Just how often have lax critics dusted off that old standby, “a love letter to the movies,” in this century past? What face could launch so many professions of amour? And doesn't so much feverish stridency and insistence suggest a profound insecurity beneath? Cinephilia is, for all the afflicted that I've known, a deeply dysfunctional affection (Truffaut: “Movie lovers are sick people”), one marked by a perpetual struggle to excuse a beloved who is so staggeringly shallow, who has so much to offer but delivers so little. So what keeps such a romance intact, and smoldering at that? Something more than dogged habit or escapist oblivion I hope; God knows we should all have better things to do with our time. For we more sentimentally inclined, I suspect it's partway the work of that same obscure beacon which holds any love's course through choppy waters; a memory of “happier times,” a wavering half-recollection of submerged possibilities lent a flattering sepia shade in the ever-increasing distance. It must be something to do with that first, flattening impression; if it's not love, than awe at first sight, when we're conquered by an image that can never again seem so huge, and the omnipresent worries of post-adolescence haven't yet begun to gnaw at the margins of the screen. In short, the pure impressions we take home from the theater when we're perhaps the same age as Tsai Ming-liang was when he first saw King Hu's Dragon Inn.

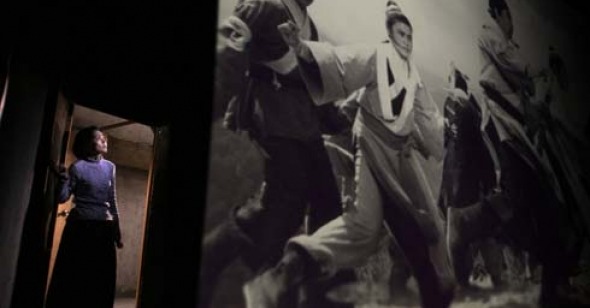

The title of Tsai's new film might suggest that the chronicler of morosely funny Taipei anomie has decided to veer into Jin Dynasty costume epics, but rest assured that Tsai has nothing so Ang Lee in store. I imagine that the nearest he'll come to King Hu–copping melodramatics is this, a film that entirely takes place in a movie theater during a funerary late-night showing of Dragon Inn, Hu's light-as-a-silk-slipper 1966 kung-fu adventure flick. It's a gimmicky sounding premise that should raise copious red flags, were it not for the fact that Liang may be the lone contemporary filmmaker who can be trusted to build something around the superficially acinematic act of watching a movie that will neither smirk with meta coyness nor wallow in awed hommage. It wouldn't even be the first time; the director has already given us one of the simplest and most indelible scenes of movie watching that exists in the cinema. In his What Time Is It There? Tsai's longtime collaborator Lee Kang-sheng sits alone in his room, lit only by the television's fluid light, watching a bootlegged copy of The 400 Blows. Drawn to Truffaut by the director's nationality, to France by a glancingly met girl who left Taiwan to study in Paris, Lee finds himself in mute dialogue with an image of Antoine Doinel who's diminished but still very much intact behind a pane of Sony glass. The unadorned presentation of the scene, which unfolds within one of the staid, static frames that comprise the entire film (both What Time and Goodbye, Dragon Inn are devoid of camera movement), is deceptively simple. But contemplative pacing and Tsai's overarching richness of conception helps us to understand the preciousness of these two heartsick, never-to-meet young men unabashedly regarding one another across a darkened bedroom, of their creators engaging in an impossible paternal-filial communion, of Lee's conjuring up his imagined love through a images of a subtitled Paris, and of our own privilege in watching and sharing all of this in the dark and solitude. With only the sparest of means, we've been located within an international, intergenerational, intertextual echo chamber of longing.

As in any Tsai Ming-liang movie, What Time Is It There? is crisscrossed by such refractions of stifled desire, the strained reaching for things inaccessible hedged away by barriers of time, distance, mortality, sexuality, and psychology. In What Time our subjects are a father and husband inaccessible through death, a daydreamed lover inaccessible across time zones, and a personal equilibrium rendered inaccessible through cultural dislocation, but the film's tensions could just as well be encapsulated by the wobbly sixties Cantonese ballad that plays out Goodbye, Dragon Inn, whose chanteuse “can't let go” of a “past that lingers in (her) heart.” In Tsai's latest that lingering past is one that belongs specifically to the movies. The film's action is set entirely within the Fu-Ho Grand, a cavernous urban cine-palace introduced during its heyday in the film's prologue. Before we've even found our seats among the capacity crowd, however, thirty years have passed; a torrential rain is lapping at the lobby, and the Fu-Ho is now anything but grand, just a declining urban theater on the eve of a “Temporary Closing” which one suspects the management has optimistically phrased as such in order to soften the blow of their establishment's passing. Our dramatis personae are the building's last few inhabitants: there's a sparse clientele of anxiously cruising homosexuals engaging in the filmmaker's usual impossibly tentative, mute nonconsummating rituals, a pair of familiar-looking older gentlemen whose eyes dampen to capacity while watching their young, acrobatic alter-egos on-screen (former King Hu actors Tien Miao and Jun Shi), one singularly attentive, moon-faced baby boy, a pining pretty-sad usherette hobbled by a leg brace (Chen Shiang-chyi), and the unseen object of her imagination, a young projectionist co-worker (Lee Kang-aheng) whom she has seemingly never met. It's an array of outsiders well fit to join the social anomalies who populate Tsai's filmography; a finer litany of cripples, crookedly beautiful melancholics, and sexually confounded breakdowns you couldn't find outside of the confines of the Southern Gothic. Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie comes to mind most of all; with her uneven gait and shy, gray look like that of some hauntingly half-remembered classmate in a dust-coated yearbook, Chen makes a fine Laura Wingfield, while the nocturnal meat-market in the Fu-Ho recalls the illicit adventures that brother Tom, standing in for a once-closeted Williams, might've found in compulsively “going to the movies.”

And this is, above all, a film about going to the movies; returning to Truffaut, one might call Goodbye, Dragon Inn Tsai's Day for Night, though the more aquatically inclined Taiwanese director, whose oeuvre is so thoroughly drenched in metaphorical waterlogging, imagines films not as trains passing in the night, but as monstrous frigates, unmoored and adrift, which carry their human cargo on a dark free-float. The stowaway-haunted interior of the Fu-Ho, where boys float and brush past each other like buoys, is a ramble of aimless corridors and storage rooms crowded by sagging, soggy cardboard. All of the walls here seem to be the same aquamarine shade of abandoned swimming pools, every corner is stained with dark tendrils of water damage, and everything contributes to the overall appearance of some great vessel's hull, where the all-pervading, echoing soundtrack of Dragon Inn approximates the moans of a pressurized below-deck. This ship's off on an under-booked farewell cruise, and the desolate few spread across this space made for the accommodation of thousands, clustering together then ricocheting apart, are fine material for Tsai's delicately orchestrated tableaux of touch-and-go souls. But so much negative space is also bound to take on a palpable presence of its own, and when one of the Fu-Ho's occupants finally speaks, almost halfway through the film's running time, it's no surprise that it's to inquire, “Did you know this theater is haunted?”

Though the facts of the theater's literal haunting are never made conclusive, Goodbye, Dragon Inn's pervading atmosphere of nostalgia, which casts a shadow from the film's first frame, has the past a palpable presence in the Fu-Ho Grand. In the movie's opening sequence it's Hu's Dragon Inn, at first run, which holds sway over the rapt congregation. Tsai begins with a séance, evoking a lost, perhaps never-existent paradise where undiluted cinematic grace gave form to a unpretentious collective dream, an era of egalitarian pop poetry eulogized by the bygone celluloid swordsmen who wearily conclude in the post-screening lobby “No one comes to the movies anymore.” When we first enter the sold-out Fu-Ho, the projection of Dragon Inn forms the axis of each successive composition; in every readjusted set-up, the film, above all, remains central. During the bulk of the present-tense narrative, however, Hu's film has been demoted to ambience, and Tsai's framings now crane vertiguously to eschew the vast screen. Though the omnipresence of the print's tinny, distressed soundtrack insinuates itself into every corner of the haunted theater, almost imperceptibly overlapping onto the individual cravings and pains of the Fu-Ho's denizens, the once magisterial work is faded from the foreground. And as Dragon Inn is reduced to a murmur, drowned out by the more pressing white noise of sadness and sex that distract its meager flock, only the face of the baby boy, viewed fleetingly but granted one of the film's precious few close-ups, remains absorbed and attentive…

I can't make any claim of Goodbye, Dragon Inn as an impeccable film: in spite of being Tsai's most overtly sentimental work, it's far from his most affecting—he's too occupied in carefully calibrating his human pinballs to generate much individual empathy—and the director's careful, framing-dependant gags err toward the over-plentiful; most of them are variations of an attempted movie theater pick-up from What Time Is It There? that's significantly funnier. But that a work which indulges in such overt nostalgia can also function as a work about nostalgia, seeing so concisely through its bleary eyes, and that a film delivering an epitaph for the classical 20th-century conception of moviegoing can make the medium hum with vitality, is an accomplishment that shouldn't be underestimated. At its best Goodbye, Dragon Inn does much more than pine for the impossibly grand movies of our memory; Tsai recognizes, respects, and loves the sweet melancholia born of unattainable longing far too much to buy it wholesale. What's implicitly understood here is that movie love is like any love; once the initial shivers have subsided and the object of affection is revealed as small and silly, just a clumsy jumble of light, one has to find a new way of loving or lose the thing altogether. The affirmation is on the screen: looking backward all the while, Tsai never once succumbs to mimicry, regression, or defeatism; he just creates a distinctly grown-up film that lets its audience think and feel.