Every Halloween, Reverse Shot presents a week’s worth of perfect holiday recommendations. Read past incarnations in our series “A Few Great Pumpkins.”

First Night:

The Bad Seed

Looking around in 2025, one might be forgiven for feeling utterly helpless in the face of evil. But what if that evil—unrepentant and irremediable—were localized in one small unit, easily overcome and physically weak? A child, a little girl in blonde pigtails, perhaps. Would that make it simpler to eradicate? And what if it were your child, and only you knew the truth about her? Framing the basic premise of 1956’s The Bad Seed as a series of questions feels apt, as it’s the kind of film that seems to talk directly to the viewer: what would you do?

This horror peculiarity fits squarely into the mold of fifties women’s melodramas (the men are ineffectual or absent entirely) even while it invents an entirely new subgenre with gruesome glee: the evil kid movie. Four years before Village of the Damned made it easy on the viewer by framing its monstrous humanoid tots as the vanquishable spawn of supernatural beings, versatile Hollywood workhorse Mervyn LeRoy’s very strange The Bad Seed locates its tiny menace in American suburban nowheresville, and what’s worse is that little Rhoda Penmark is not the result of extra-terrestrial impregnation. Unflaggingly polite and well-spoken, she’s a sociopath who’s all too human, easily manipulating those around her into getting what she wants, and becoming murderous with rage when she doesn’t. The film, based on a hit 1954 Broadway play by Maxwell Anderson, which was in turn based on a novel by William March, a poor, troubled soul who struggled with his sexuality and who died mere months before the play premiered, asks basic—and eternally troubling and unresolved—questions about nature versus nurture. This evergreen horror topic reared its head again in this year’s prestige streaming polemic Adolescence. But even that solemn inquiry into the harmful effects of rampant technology and incel culture on our youth, in trying to find answers as to why an angel-faced 13-year-old would coldly murder his schoolmate, leaves room for us to see him as a frightening, rotten aberration as much as a victim of his time.

The Bad Seed forgoes self-seriousness, but it’s certainly in the business of diagnosis. The rise of mainstream psychoanalysis in the forties led to wider armchair psychologizing in the fifties, and Anderson’s play revels in having its characters identify and categorize the functional sociopathy of its pipsqueak fiend. Rhoda’s suffering mother, Christine (Nancy Kelly), grows suspicious that Rhoda (11-year-old Patty McCormack) was responsible for the brutal death of little Claude Daigle, who drowned at the school picnic and was found with bruises on his knuckles. And while their busybody upstairs neighbor Monica (Evelyn Varden) claims with no small amount of self-satisfaction that she’s “a student of psychoanalysis” and is fascinated by historical murderers, her love and admiration for little Rhoda’s politesse blinds her to the child’s wickedness.

The only other person who sees the potential for evil behind those bright eyes and freshly scrubbed apple-cheeks is the apartment building’s toad-like handyman Leroy (Henry Jones), who has the “mind of an eight-year-old boy,” is treated with condescension by everyone, and sleeps in the cellar. Perhaps as a way of getting back at the privileged middle-class snobs he caters to, he teases and taunts the child, accusing her of maleficence. The tragic Mrs. Daigle, Claude’s grieving, alcoholic mother, played by Eileen Heckartcalls Christine a “superior person,” evidently resentful of the Penmarks’ status and money. The question of what makes a human “superior” or “inferior” haunts Christine as well: while trying to uncover the origins of her daughter’s nature, asking whether evil is learned or inherent, a product of environment or heredity, she discovers an awful truth about her own birth mother. Is violence inherited? Can it skip generations?

This is dark, silly, but also genuinely nasty stuff, and, while keeping its horrific violence off-screen, The Bad Seed gets under the skin in ways unlike any other movie. Its bright, even lighting and performance blocking—which have led many over the years to label it with the dreaded “stagebound”—actually serve to make it all the more disturbing and stultifying, a portrait of American anonymity concealing a festering dread. (Don’t miss the paintings on the apartment’s walls, featuring unsettling, silhouetted figures and ominous houses, all obscurity and shadow.) It might have been the “stagiest” mainstream American horror movie since Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931), which was hampered by early sound recording limitations, but The Bad Seed’s “staginess” is central to its power because the things that are spoken of so frankly by its characters, in long, tortured monologues and harrowing two-handers, are otherwise unrepresentable. And the staid aesthetic is matched beat for beat by the demonic theater-kid energy of McCormack, who had originally performed the role on Broadway at age nine—an even more shocking age for a character who, over the course of the film, commits such off-screen atrocities as beatings, drownings, and burning a man alive.

One might wonder how such material could have ever passed muster with the entrenched Production Code. It barely did, but, as with so many films following the 1954 retirement of the Production Code Administration’s hard-liner Joseph I. Breen, the bad stuff got through after no small amount of finagling. When Warner Bros. first brought the property to the PCA, Breen’s successor Geoffrey Shurlock told the studio it was in violation of the Code, Section 12 of the Special Regulations on Crime: “Pictures dealing with criminal activities, in which minors participate, or to which minors are related, shall not be approved if they incite demoralizing imitation on the part of youth,” and furthermore, “The identification of youngsters with Rhoda, the eight-year-old, will be very complete. They will understand her effective killing of three persons who stood in her way, while at the same time, since Rhoda is a poised and charming child, they will completely miss her psychotic and tragic nature.” It was considered out of bounds even for Billy Wilder, who wanted to do it and asked Shurlock for a report on the film.

Fair spoiler warning here for this 70-year-old film, but it’s difficult to talk about The Bad Seed without gesturing to its oddball conclusion. Ultimately, LeRoy’s version at Warner Bros. was allowed to move forward on the condition that the ending would be altered. In the play, Christine decides to kill Rhoda with sleeping pills then off herself by gunshot; the final, terrible twist shows that Rhoda survived, will now live solely with her adoring but clueless dad, and all knowledge of her atrocities died along with her mother. In the film, Christine somehow survives her attempted suicide, and Rhoda, after recovering from the overdose, is given a Code-approved comeuppance: the God-like retribution of a lightning bolt. Hilariously, because of the Code, a major studio film was encouraged to bump off a kid in extravagant fashion.

To abruptly shift gears away from this shocking over-correction, the film then cuts to a playful “curtain call” of the entire cast. “As for you!” Kelly tsk-tsks, wagging her finger at McCormack before putting her over her lap and spanking her. It’s a presumed relief for the audience to remember these are all just happy, smiling actors playing parts. But it’s also futile: we’ve been exposed to evil, and you can’t stuff evil back in the box. —Michael Koresky

Second Night:

Halloween III: Season of the Witch

It begins on an empty road, in the dark vacuity of a California night, on the gray periphery of the city, where parking lots are wrapped with chain-link fences and the husks of unwanted cars are stacked. Synth notes scurry anxiously before a scared man comes running down the street into frame, lanky limbs flailing. On his trail is a car with blinding headlights, full of men garbed in vague professional attire and stoic in demeanor, searching, prowling, dangerously bland, determined.

The man is attacked, improbably escapes, collapses at a gas station in gothic lashes of rain moments after intoning “They're coming.” He has a mask clutched tensely in his fingers. An empathetic mechanic brings him to the hospital. Our unlikely hero, Dan Challis (frequent John Carpenter collaborator Tom Atkins), a doctor and deadbeat dad with an ex-wife and drinking problem, is called to the hospital to attend to the mysterious man; there, with profound terror, the man summons what little energy he has left and offers his final cryptic words: “They'll kill us all.”

One of the menacing men in vague professional attire arrives, and, with black-gloved fingers, crushes the poor guy’s skull, the mask still clenched in his quavering hand, which soon goes limp. The assassin departs, menacing in his undeterred, languorous gait, down fluorescent halls to his car. Challis pursues but is too late: the man sets himself on fire, leaving behind an inferno of gnarled plastic remnants, smoldering machine parts, and a burning enigma.

The dead man's daughter (Stacey Nelkin) shows up, and she and Challis collaborate to figure out what's going on. What they discover is weirder than anyone—the characters, the viewers—could possibly imagine.

Carpenter and Debra Hill never wanted their seminal Halloween to spawn sequels in the first place; they immediately recognized the trend they had unwittingly engendered and understood that Halloween's influence would quickly devolve into infantile stupidity and splatter. They only worked on the first sequel, bored as they crushed cans of beer while pecking away at their typewriters, because the producers were going to make the film whether they were involved or not. So, they came up with another idea: turn the Halloween franchise into an anthology of standalone films centered around that spookiest of holidays. It was a daring idea that jettisoned the standard conception of sequels, the diminishing echoes, ignoring what mainstream moviegoers wanted, which was—still is—more Michael Myers. Fading echoes on an icon.

Halloween III: Season of the Witch was written and directed by Tommy Lee Wallace, who performed a panoply of roles for Carpenter’s early films: as sound effects editor and art director on Assault on Precinct 13; production designer and co-editor of Halloween and The Fog; and, for a few shots in the first Halloween, he played The Shape, whose iconic mask he also repurposed, thriftily, from the Shatner mask. Wallace turned down the directorial job for Halloween II, feeling that he wasn't ready, but when Carpenter offered him the third film, he agreed to write and direct. (He would also later direct Vampires: Los Muertos, a very good low-budget sequel to Carpenter's Vampires, starring Jon Bon Jovi.)

In Wallace's film, an iniquitous Irishman named Conal Cochran (Dan O'Herlihy) wants to pull the best Halloween prank ever. He runs a very successful company, Silver Shamrock, which makes gags and gizmos for the young and young at heart. But their new big-seller, which will certify their legacy, consists of a trio of grotesque/cute masks for kids: a skull with gaping lightless eyes, a crooked jack-o’-lantern, and a witch, green and ugly. Each is bejeweled with a logo-stamped button on the back which, we learn soon enough, contains magical splinters of Stonehenge, or something. It is all very silly, of course, yet the delirious kind of smart only genre cinema can be.

The masks are the must-have costumes of the year, like Jason and Freddy would be later in the decade, and the film shrewdly plays with the influence of the famous Michael Myers disguise on the holiday. The masks are advertised on every channel on every television with a mesmeric commercial featuring a catchy jingle (reminiscent of “London Bridge Is Falling Down”) and a pulsating, affable orange pumpkin. The ads promise a big giveaway on Halloween night, when all those kids who have convinced their parents to buy them the masks will gleefully gather around their TV sets in suburban living rooms across the country. The song and throbbing pumpkin will trigger nasty death, the baleful masks turning the kids’ encased heads into writhing swarms of bugs and venomous snakes. It’s a much more creative kill than a knife in the gut.

Why is Cochran doing this? For a laugh. Ha ha. His dastardly scheme, he tells us, harks back to the olden days of eldritch yore, when people took Halloween seriously, before kiddies in costumes and candy commercialized it. It's an evil made for the movies—ridiculous, violent, rich with macabre metaphor, visually resplendent.

If Halloween answers the audience’s pesky question, “Why is Michael Myers killing babysitters?” with a resounding, dogged, ambiguity, then Season of the Witch answers its own “Why?” the opposite way: with a deranged and explicit explanation that, in its sinisterness, its profound strangeness, the tarry black sense of amusement it inspires, is truly unexpected. When Challis figures out the scheme and tries—and fails—to stop it, Cochran catches him, wraps a mask around his face, and straps him to a chair. With equanimity and conviction, Cochran delivers a deranged showstopper of a monologue on the spiritual beauty and historical importance of killing children on All Hallows’ Eve. He departs, leaving Challis there to watch television. On the tube plays the original Halloween, censored for public broadcast and cropped to fit; he must witness the film, awaiting that fatal pumpkin. Carpenter’s mostly bloodless film was a galvanizing influence on the slasher genre, a cultural phenomenon with apparently eternal life, as the TV commercial for the film says, while Season of the Witch most certainly is not. Here, Carpenter's classic is a portent of doom, and the scene is perhaps a gag about the pearl-clutching claims from priggish moms and dads that violence in film directly creates violence in real life.

Season of the Witch is a bold and bizarre film, spiritually faithful to Carpenter’s anti-authoritarian, anti-capitalist anger, with its depiction of maniacal mass production and the insidious seepage of greed into every facet of life—every life. It also shows an aesthetic kinship to Carpenter, with Dean Cundey shooting it in glorious Super 35, and Carpenter himself scoring, some of his best work. The key to the film’s singularly goofy greatness is that Wallace, an apt pupil, has a singular vision (and for a neophyte auteur!), and refuses to give in to listless reverence. Yet the film failed spectacularly, earning the ire of fans who wanted more of the same and grossing much less than the two previous films, while critics scoffed. Thus, Carpenter and Hill abandoned the series, and Michael Myers, that lumbering lunatic, with his Shatner face and big knife, returned to stab kids again, and again, and again. It makes you think of Challis bellowing into oblivion at the end: “Stop it! Stop it! Stop it!” —Greg Cwik

Third Night:

The Black Tower

No matter which direction you choose to run, it’ll always be in front of you, staring back over fences and treetops and terrace houses. It sounds like a riddle of the Sphinx—and you might be eaten alive depending on how you respond. This is some cinematic witchcraft from British experimental filmmaker John Smith: The Black Tower (1987), in which the laws of physical reality are no match for the racing imagination.

“I first noticed it in spring last year,” the narrator (Smith, in his distinctive lilt) recalls at the start of the film. We hear his voice—calm, at a cool remove—over a black screen. Or so we think. The narrator goes on to detail his memories of a strange black tower, improbably materializing all over London. We glimpse it beyond a busy highway, jutting up above stone walls, lurking behind a church. With each new vantage on the tower, Smith reels the viewer in closer. This building is not just everywhere; it is in pursuit, hungry. And if we accept that, then maybe, when we gaze upon these intervals of black screen, we’re seeing things from the narrator’s point of view. Maybe we’re inside the tower with him.

In reality, this eerie edifice was just a water tower, a specter over the grounds of Langthorne Hospital in East London. It was demolished just a few years after The Black Tower premiered, which serves up an extra helping of hauntology. But its functional purpose does nothing to explain why it looked so ominous: a jet-black Monopoly house perched atop a brick chimney, it resembles a cutout in the cheerful blue sky, as if James Turrell etched a portal to the void. Smith could see this tower from the window of his apartment at the time, and was captivated by its non-reflective paint, which revealed no dimensionality or detail; the film was a way for him to explore that uncanny effect. As Smith captures the tower from different angles and distances, the film stalks a wide circle around a fixed point, amassing a pointillist photo album of the area. The film ends with a new narrator (Anna Hatt) catching sight of the tower for the first time.

It’s hard to resist the spell Smith casts. As we speak, I have several browser tabs open to triangulate where the tower once stood and fill in the gaps in its history, but in the early 2000s, the photographer Ian Walker took this even further. Armed with a map and context clues from the film, he trudged out to the neighborhood surrounding Langthorne Hospital and attempted to draw up a shot diagram. In his photographs, we see how the area has changed since Smith filmed there: sections of the old hospital have been torn down, high-rises have been razed. Many structures and fences present in Smith’s compositions remain, but not the tower. In the wake of Smith’s film, Walker’s photographs instill an uncanny impression that the tower is not gone, but invisible—as if these buildings of the past are still present.

There’s a link between housing and haunting in Smith’s filmmaking. At one point in The Black Tower, Smith shows us the mid-’80s demolition of tower blocks at the Hackney Marshes: he flickers between two images of the landscape before and after the demolition, making the building appear and disappear in a flash, and then, jarringly, there is motion, the building crumbling into the ground in a sudden blast. These apartments were built in the ’50s as part of an idealistic public-housing initiative but fell into disrepair due to governmental neglect. The footage ruptures the procession of angles on the tower, and leads us to question the permanence of buildings anchored in solid ground; if they can be torn down, maybe it’s not so outlandish that they can also follow us. But how? A later film of Smith’s, Blight (1996), seeks to embalm the lives and memories of the East London residents whose homes were thoughtlessly bulldozed to make way for the M11 Link Road. As Smith loops images of builders knocking down walls, he makes this story of destruction less linear. Snippets of interviews with residents, chopped and remixed into poetic fragments by Eyes Wide Shut composer Jocelyn Pook, seem to hex the demolition work from beyond, smuggling the spirit of the place out of the rubble.

Many of the formal devices in Blight are familiar from The Black Tower, like color fields that gradually reveal themselves to be objects, and synesthetic associations between images and sounds. But the tell-tale heart of this film is its pulse-quickening voiceover: the impossible seems so tempting, so oddly logical. You could question the artifice of the editing, but it’s more fun to trust the voice, to doubt your sanity. Smith released his first film in 1975, just after the initial materialist wave that inaugurated the London Film-Makers’ Co-op—he took a course with Peter Gidal at the Royal College of Art—but felt a step apart for his interest in the seductive potential of narrative, finding structural film fairly dry otherwise. “For me, the films that are most interesting are the ones that in some way invent their own language,” Smith told The White Review.

Perhaps because it is so direct, plainspoken, and economical, the language of The Black Tower convinces us not just to suspend our disbelief but also to let it take us somewhere. And the film leaves that direction open; some have read the encroaching tower as a metaphor for depression, while Smith maintains the script is pure sci-fi pastiche (both, of course, can be true). The horror can come from anywhere. You’re running, and the tower keeps flashing in front of you, a new angle manifesting with each blink. There’s a sliver of blue sky in the upper right-hand corner of the screen, but it’s getting smaller by the second. I first noticed it in spring of last year. —Chloe Lizotte

Fourth Night:

Cure

Contrary to what you might expect from a film that starts out with a man killing a prostitute—and then, shortly after, another man killing his wife—the reference to the Bluebeard story at the beginning of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure isn’t entirely about misogynistic violence. In the eerie opener, aglow in clinical white lights, a female patient named Fumie (Anna Nakagawa) reads a German rendition of the classic folktale: about a repulsive yet extravagantly wealthy man known for murdering his wives. Arguably, it’s not Bluebeard’s fault. Each bride, he had trusted with a set of house keys, allowing them to go about the castle as they pleased—with the exception of one forbidden room. When they go in, anyway, when they gaze upon his vault of corpses, they seal their grisly fates. Cure, too, is about a dangerous thirst for knowledge. But if Detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho), Fumie’s husband, is the one desperate to unlock the secret room, what’s inside will reveal less about the crimes of others than his own capacity for wickedness; the bloody chamber that lies within.

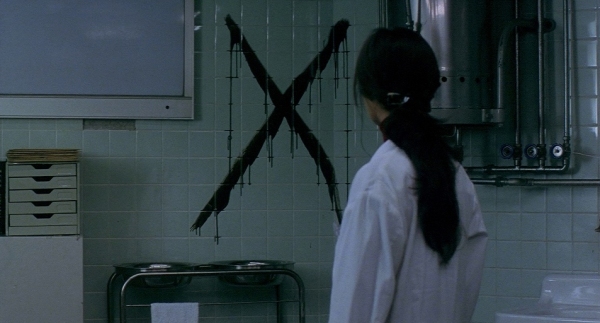

In this sense, Kurosawa’s breakthrough—made after a period of working as a gun-for-hire on pink films and direct-to-video joints—echoes a running theme in detective dramas, in which the search for truth curves back, floodlighting the searcher. I think of David Fincher’s Se7en (1995) and Zodiac (2007) as exemplars of this cruel exposure, which flattens the moral impetus behind the investigators’ justice-seeking by teasing out the latent darkness in their obsessive crusades. Cure, likewise, tracks Takabe’s gradual deterioration after he is assigned a case of identical murders, in which an “X” is carved into the victim’s throat and the perpetrator, as if under a spell, can’t explain why they did it. There’s a menacing sense of calm to the film, accented by long, moderately distant takes that frame the characters like dolls in a playhouse, powerless against the mysterious forces that control them. In this regard, it’s less gritty procedural than woozy macabre poetry in the vein of Fritz Lang or Jacques Tourneur, with supernatural elements employed not to stoke spectacle but to anchor the story to an irreducible unknown. As Takabe’s psychologist partner, Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), explains: “People like to think a crime has some meaning. But they usually don’t.”

Early on, Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), a former psychology student with a shaggy hairdo and grungy pullover sweater, emerges as the link between all the murders. Like the lovechild of Kurt Cobain and Dr. Caligari, Mamiya is a hypnotist with the air of a blissed-out slacker. He seems to remember nothing about himself, frustrating his future victims—an elementary school teacher he meets on a windy beach; the cop who arrests him; the doctor who examines him during his detainment—with non-answers and insistent questioning about their lives. With a lighter’s flame or a splash of spilled water, Mamiya is able to seize his interlocutors' minds, inciting them to violence. The film’s increasingly frenetic editing patterns; its oneiric style—the way it lingers on the flickering fire or the drip of water, pooling on the floor from a leaky faucet—subjects the viewer to Mamiya’s hypnosis. And like his ultimate target, Takabe, our grip on reality slackens; desires, fears, and death wishes seem to rush onto the plane of waking life. For Takabe, this means vivid hallucinations of his sick wife, for whom his resentment grows the more Mamiya gets under his skin. In one scene, he envisions her dead and hanging in the kitchen; in another, we see them riding a bus, with a luminous daylight background achieved by rear-screen projection conveying gauzy artifice. When we see Fumie’s corpse being wheeled down the hall of a hospital, her neck bearing a bloody “X,” we can’t be certain whether Takabe has indeed slaughtered her or if the image exists merely in the depths of his brain. The film is not to be trusted.

Yet it’s precisely this slipperiness that gives Cure its haunting power. The terrible urges we repress to sustain a functioning society, here, surface thanks to Mamiya’s inducements, which scramble the distinctions between the conscious and unconscious, truth and illusion. The conditions of reality itself are changed by tearing down these walls; by recalibrating our psychic proportions. The word “evil” has always struck me as a lame and inadequate way of defining the world’s horrors; as if they happen on account of some demonic power, some corrupting entity, that exists outside the natural order. Mamiya sees “all the things inside” his targets and draws them out, aggravates, and externalizes them. His might be some kind of magic power, but this fictional dimension is just a tool used by Kurosawa to demonstrate the ease, the mere work of calibration, with which seemingly normal people are liable to crack and spill forth their ugliest bits. Real “evil,” then, is latent in us all: it’s in the man waiting next to Takabe at the dry cleaner, who curses under his breath about, presumably, some issue in his workplace, before reverting back to a polite demeanor when the employee returns; it’s in the waitress in the film’s finale, who goes about her shift, and picks up a butcher knife; it’s in Takabe, who would look innocent enough sipping tea at his regular dinner spot had we not been so intimately immersed in the dark matter of his soul. Whether or not he’s guilty is beside the point. —Beatrice Loayza

Fifth Night:

Christine

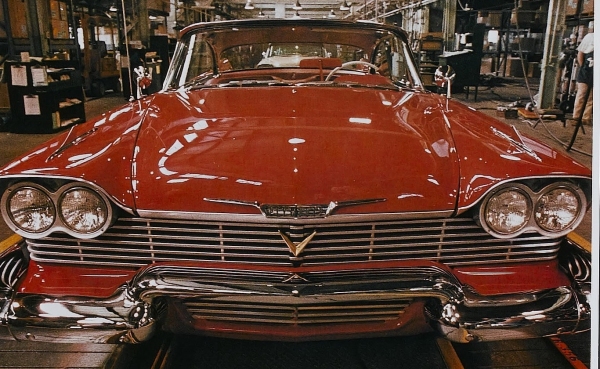

As liberal democracy frays and dissolves and it becomes undeniable that the over-rhapsodized but still real 1950s postwar American era of peace and relative middle-class prosperity was merely a historical aberration and illusion, the signifiers of that era become increasingly more like taunts and sinister harbingers. In Stephen King’s novel Christine and John Carpenter’s film adaptation—both from 1983—the title character is a garishly blood-red, shiny, and oversized 1958 Plymouth Fury that resurfaces out of context in small-town America in the late 1970s. The car serves as an ideal symbol for the unwelcome, malevolent influence of the seemingly carefree consumerism that flowered during its formative years. And while it’s easy to play pin-the-metaphor on many of the central objects/settings/characters in King’s novels (the book leans more banally on the car being possessed by its murderous previous owner’s spirit), the film concludes on the initially baffling line “God, I hate rock and roll,” supporting the reading of it as a grumpy rebuke of ’50s nostalgia.

For Carpenter, Christine followed a masterful five-film run of genre classics (Assault on Precinct 13, Halloween, The Fog, Escape from New York, The Thing), and it was his first to evince a bit of clunkiness and detachment with the material. The director has said that he did not find the novel frightening and took the job as a career move after The Thing’s disappointing box office. And yet it is still a wonder, palpably the product of a filmmaker working in “God mode,” with its author’s signature stylistic touches in every scene, starting with the sensual dolly-drift down the Detroit assembly line during Christine’s violent, “Bad to the Bone”–scored “birth.” Flashing forward 20 years to fictional Rockbridge, California, we meet nerdy (skinny, glasses) “Arnie” Cunningham (Keith Gordon), a high-schooler in a milieu of pimply locker-room talk of “fellatio,” “beating off,” and his sensitive-jock pal Dennis’s declaration that “it’s ’bout time we got you laid.” Arnie is bullied by a crew of degenerates led by the sublimely named “Buddy” Repperton, looking about 30 and himself a ’50s throwback with his fondness for switchblades, and henchman who spout things like “How do you like that, dickface?” At home, Arnie’s battle-axe mother (Christine Belford) doms his beta dad, and he only finds confidence once he meets Christine, which he buys from a creepy aged loner in a body brace (Roberts Blossom). “For the first time in my life I’ve found something uglier than me,” Arnie tells Dennis (John Stockwell), a line that captures the kind of low self-regard so common to teens (“You’re not ugly. Queer maybe—but not ugly,” Dennis reassures him.)

The influence of Christine, the multivalently metaphorical car that’s also a stand-in for its protagonist’s repressed pubescent rages and desires, transforms Arnie into something of an Evil Fonzie, a greaser with newly popped collars, slicked hair, and cheapjack swagger, who struts into Dennis’s hospital room (the latter was injured on the football field while distracted seeing Arnie making out with a babe on the sidelines) and leaves his pal with a sixer and a book of 5,000 dirty limericks. Arnie’s about as terrifying as Bart Simpson, and his initial breaking bad is clearly a source of derisive amusement for Carpenter, though the amiable goofing sours when Christine starts terminating Arnie’s enemies one-by-one. This “malevolent force picking off the bullies” section, as well as the final shot zoom-in on the “corpse,” invite comparisons to De Palma’s much richer and more elegant earlier King adaptation Carrie, but Carpenter cannot be blamed for inheriting the weaker source material. Eventually, the teen body count brings a detective to Rockbridge, played by Harry Dean Stanton, whose real, effortless cool shames Arnie’s puerile peacocking.

Classic Carpenter set pieces abound, like the possessive car trying to pick off Arnie’s trapped date, Leigh (Alexandra Paul), lit from under the dash as if by the Kiss Me Deadly mystery package, at a drive-in screening of Thank God It’s Friday (1978); and the famous scene of a grievously damaged Christine regenerating itself (effects supervisor Roy Arbogast accomplished the feat involving internally-mounted hydraulics and backwards-running film). Gordon, who had already appeared in two classics (All That Jazz, Dressed to Kill) before this and who went on to become a prolific film and television director, brings an appropriately off-putting and overcompensating spazziness to Arnie, whose dying caress of the vaginal “V” on Christine’s grille, while the car mournfully plays Johnny Ace’s “Pledging My Love,” is genuinely moving. Dennis and Leigh ultimately mount and annihilate Christine with a bulldozer, and the killer car ends up cubed at a junkyard, where, along with the detective, they seem to hear it emitting a final wheezing sputter of 1950s rock, another missive from the era that refuses to die. But it turns out to be a sneering grease monkey’s boombox. —Justin Stewart

Sixth Night:

What Lies Beneath

There is no film in the Robert Zemeckis oeuvre more abject and terrifying than The Polar Express (2004), his initial foray into motion capture maximalism. In its characters’ blank shark eyes and disjointed J-horror movements, we can witness the stirrings of what has metastasized into today’s AI-generated TikTok brain rot. It’s a plasticine post-human Christmas movie, the kind of product you could imagine the infernal machine-world of The Matrix generating algorithmically to entertain the human slaves that provide its energy source. Just looking at an image of one the film’s myriad CG Tom Hankses is enough to send a shudder down my spine. It is one of the most deeply unpleasant films, like a G-rated Saló holiday special—somehow even more troubling than Forrest Gump.

Frightening as it may be, I would urge you to stay far, far away from The Polar Express this Halloween season. Instead, turn your attention to the quite pleasingly scary thriller Zemeckis made just prior: 2000’s What Lies Beneath. Shot during a break in the production of Cast Away, scheduled so that Hanks could drop weight and grow a beard—with its entire crew ported over from that other film—What Lies Beneath is a Hitchcock-humping hoot, an improbable contraption that collects pieces of Rear Window, Vertigo, Psycho, Rebecca, and Spellbound, and amalgamates them with the filmmaker’s questionable taste and bravura technique into an overlong, theme park ride of a movie. It’s a ghost story, too. The pileup of suspense and horror movie tropes should have reasonably toppled any movie under sheer tonnage, yet late 1990s Bob Zemeckis, shameless, Academy-lauded, thick in his imperial phase, was exactly the right filmmaker to glue the pieces together.

Michelle Pfeiffer and Harrison Ford star as husband and wife Claire and Norman Spencer. He’s a generic movie scientist who works late hours at a lab and is writing a big paper. She stays home at their gorgeous lakeside Vermont manse and wanders the structure like a specter. As the movie opens, their daughter Caitlin heads to college and they become empty nesters, leaving Claire with even more time on her hands. Her first obsession becomes spying on the neighbors next door, who fight and fuck so audibly and often that it sets the inactivity of her life in stark relief. After witnessing a particularly violent confrontation, Claire becomes convinced a murder has taken place. Eventually she confronts the husband at a crowded party at the university, only to be met right then and there by the wife, very much alive.

Mortified, Claire retreats further into signs and portents. She sees ghostly faces in water that look suspiciously like her, hears things bump in the night. She reads too much into everything and decides to host a seance. Zemeckis switches his mode to haunted house–eerie on a dime, the camera’s creep through empty rooms suggesting something horrid is soon to be revealed. There will be jump scares. From its beginnings as an homage to Rear Window, What Lies Beneath has morphed into a knockoff The Uninvited—is Claire really connecting with a spirit, or has she lost her mind? There are rumblings of a car accident a year prior, dire family histories hinted at but never fully articulated (for, as the title suggests, they lie beneath). Concerned hubby Ford furrows his brow with concern and purses his lips, yet it’s clear all the WASP-y, constipated, we-don’t-talk-about-it hokum is pointing toward something malign about to surface.

I won’t reveal that “something” here—if you’ve seen a Zemeckis film you’ll rightly expect it to be ridiculous and gaudy and rendered with such skillful conviction that you can rightly ignore boundaries of good taste or sense. (The director is well-served by Pfeiffer and Ford, who fling themselves fully, bodily into the melee.) The giddy climax of What Lies Beneath represents what’s best about Zemeckis’s cinema as a whole—that joyous kid-in-a-sandbox feeling of possibilities waiting to be tapped, of new forms of play being invented on the spot. To be fair, this same sense has also resulted in the worst excesses of his cinema, and this central paradox is what puts him among our most persistently confounding contemporary auteurs.

In the curious career of Bob Zemeckis, The Polar Express isn’t really an anomaly because any one of his films seems anomalous to the others. After What Lies Beneath, he would go on to lose himself for some years in the digital landscaping—Beowulf, A Christmas Carol, The Walk. His most recent films, Welcome to Marwen, Pinocchio, and the very great Here similarly forefront technology but play almost like a series of digi-apologia for earlier, more risible experiments.

What Lies Beneath remains arguably his last movie created at a truly human scale, with small groups of actors performing in frames captured by film cameras being operated by craftspeople standing in a room with others who hold boom poles, move equipment, hang lights, and overeat at the craft services table. Itis a deeply derivative film. Its constituent parts have been handled better by other movies and directors. Who cares? Its magic lies in its combinatory audacity (or lunacy?), which makes everything feel familiar and new all at once. We know what’s coming in the famous bath sequence—the pattern of the shots tells us to expect a fright—and even though Zemeckis draws things out past the breaking point, we’re powerless. We see the face floating in the water, the strings stab on the score, Pfeiffer screams, and so do we. And then all that’s left is to sit in the dark and wait for the next scare. —Jeff Reichert

Seventh Night:

When Evil Lurks

Because life is messy and fear comes in many different shapes and sizes, a folk horror film about possession which borrows liberally from films about infection requires a clear set of rules to help situate the action. Argentinean director Démian Rugna’s beautiful but harrowing When Evil Lurks takes place in a world of rules, which the audience discover one by one, but which the protagonists already know. At the film’s start, it’s well established that certain members of its rural community have been victims of demonic possession: its origin is not explained further, because the characters have no need of explanations. Instead, we are thrown straight into the coping phase.

For the audience, the gradual unpacking of this world becomes almost unbearably horrific, and the pervading, escalating dread is amplified by the counterintuitively bureaucratic way in which the characters go about the business of protecting themselves from harm. The possession behaves in this film like an infectious disease, capable of being passed from person to person (or animal) by numerous means, creating unfortunate victims/carriers known as “rottens.” A key edict is that electrical appliances are forbidden as they are strong conductors of demonic forces; another is that firearms are strictly prohibited because the dispersal of blood is a vital contaminating factor. The more we learn of them, the more we realize the inevitable challenges inherent in these restrictions. Early in the film, a farmer, overcome by anger, shoots a goat that has become possessed (shades of Black Phillip in The Witch) and his wife, thus infected, promptly kills him with an axe and then commits suicide. The shocking immediacy of this sequence is also grounding: the rest of the film plays out over our dramatic understanding that when the rules are not followed, a terrible reckoning awaits.

The plot of When Evil Lurks turns on a failure of process: three characters, tasked with disposing of a “rotten,” allow their grisly cargo to fall off the back of a truck. They lose sight of where this occurred, but too readily abandon their search and abdicate responsibility for the loss, thereby ensuring more widespread—and unquantifiable—infection. Two strong ideas emerge: the first is that the story has taken up the suspenseful grammar of a crime thriller (wherein, say, two policemen have allowed a violent criminal to escape and the audience can only dread the repercussions); the second is that where members of this community flout the rules, or cut corners because of hardship, impulse, pressure, moral quandary, or indolence, then mayhem ensues. Rugna—speaking at Austin’s Fantastic Fest in 2023—explained that he was inspired by the alleged abuse of pesticides in Argentina’s Cordoba province at the beginning of the century. By using harmful chemicals to kill bugs on soy and corn crops, the U.S. firm Monsanto was supposedly causing soaring levels of cancer and congenital birth defects in local children. As in real life Cordoba, the institutions designed to protect and prevent (police, health service, the Church) are respectively apathetic, overrun, and absent in When Evil Lurks. It is left to the populace, living in poverty and insecurity, to help themselves as best they can. Their code of conduct—unusually for folk horror—is irreligious: they are relying on solidarity and discipline alone to survive.

Amongst many wrenching and lurid sequences in When Evil Lurks, the one that stays with me most vividly is the first encounter with the central “rotten,” Uriel—named for the biblical archangel who figures in Haydn’s Creation and prominently in Gnostic and folk Catholic tradition as one who collaborates with demons. The protagonists, Pedro (played by the striking, gaunt Ezequiel Rodriguez) and his brother Jaime, are led matter-of-factly into Uriel’s dank, squalid grief hole of a bedroom. The apparition on the bed is barely human, resembling someone from an exploitative TLC documentary about monstrously obese people crossed with someone from another exploitative TLC documentary about terrifying dermatological conditions. Uriel is carrying a demon, so is on his way to being possessed in the manner of Regan from The Exorcist, but by contrast to Regan he is merely a stricken carrier, passive and immovable, wallowing in his own abjection and suppuration. By the end of the scene, the helplessness of his condition has become more overwhelming than the threat he poses or the repulsive nature of his appearance. When Evil Lurks tacks towards the emotional dynamics of traditional infection pictures (The Crazies, Rabid) or replacement stories (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Thing) wherein a friend can suddenly transform into an enemy…but in the person of Uriel we are offered something of the forlornly destructive potential of King Kong as well. This singular cocktail of disgust, pathos, and banality provides a truly atypical antagonist. Elsewhere, the hardship defining the community complicates our own emotional response to the numerous lapses of judgment the characters commit: the film provokes compassion and terror in equal measure. At its heart is a robust humanism that accompanies us like an avuncular companion through its most sanguinary excesses.

Children, given the film’s inspiration, are not exempt, and a pivotal sequence with a dog and a six-year-old girl constitutes a small masterpiece of suspense direction. Ultimately, Uriel’s rotting carcass ends up stored under the floorboards of a school, thereby infecting/possessing—at the film’s upsetting climax—all the schoolchildren, who band together and commit unspeakable acts of violence. The formidable demon with whom Uriel was pregnant finally births, presenting as a naked, blood-drenched infant of quite awe-inspiring malevolence. The imagery is not subtle, but nor is it forgettable. —Julien Allen