In this weekly column, one writer will send another a new piece of writing about a film they have been watching and pondering over, in the hopes that this will prompt a connection—emotional, thematic, historical, or analytical—to a different film the other has been watching or is inspired to rewatch. This ongoing column will be in the spirit of many past Reverse Shot symposiums, in which writers found connections between seemingly disparate cinematic works, and it will also help us maintain personal connection among our writers and our readers.

Only Yesterday

In these lazy days of summer I’ve been browsing through various online feeds, piecing together the season. On Tumblr, I came across an excerpt of Clarice Lispector’s 1977 novel The Hour of the Star: “She thought she’d incur serious punishment and even risk dying if she took too much pleasure in life. [...] She had what’s known as inner life and didn’t know it.” I haven’t read the book. I imagined, however, that these two sentences might also work as an epigraph to Isao Takahata’s 1991 Only Yesterday.

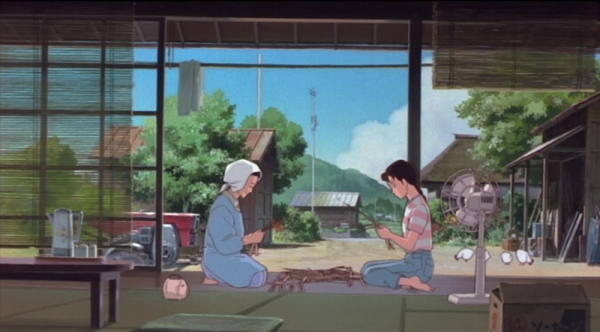

The anime film follows 27-year-old office employee Taeko, whose hard-earned vacation takes her from the apartments of Tokyo to the safflower fields of the countryside, where she enthusiastically assists locals—the family of her sister’s husband, including a handsome farmer named Toshio—with the harvest. But what should otherwise be a rewarding and relaxing time sends Taeko spiraling into anxiety over her future. She begins aimlessly wandering through the events of her childhood (specifically those from when she was ten years old), hoping to find a revelation about the past that might shine a light on what to do next. The lightened frames of these flashbacks have faded corners; for the adult Taeko, they are of ambiguous detail and opaque meaning. According to a Hayao Miyazaki fan website, the English translation of the film’s Japanese title, Omohide Poroporo, describes memories trickling down “like teardrops or beans.” I imagine her scrolling down a page, moments passing by one image at a time.

At age ten, Taeko’s a much livelier little girl to whom everything is a disarming discovery—the bitter taste and tough texture of an unripe pineapple, the flutters of first love, the embarrassment of picking up menstrual pads from the nurse’s office. But even at such a young age, Taeko is often told by others that she is too loud, too dumb, too stubborn—too much of herself. (“She took too much pleasure in life.”) And as the girl grows, we watch as she shrinks and shrivels into a more appeasing woman, one instance of rejection at a time.

Tiny lines of disappointment appear across the faces of family members frustrated with Taeko’s obstinate naïveté. Two small dashes appear on the jaw of Taeko’s stoic father at the sight of her shoeless feet on dirty ground. Unable to express his rage in words, he clenches his jaw and slaps her instead—he does not apologize. (”That night I couldn’t sleep,” the adult Taeko recalls, “wondering why it was always me.”) When Taeko overhears her usually timid mother cry out, “That child is not normal!” we see, in close-up, that her thin brows are arched in disgust. As an adult, she buries the trauma from this period beneath a dull office job and a façade: a reverence for rural life, a boisterous laugh, an avoidance of romance or marriage or anything like it, so as to do away with love and intimacy altogether. In fact Taeko’s smile lines, her one distinct feature, are not signs of happiness but a contorted sadness, grief for a lost girl.

Picking safflower seeds and preparing the plants to be turned to dye is a temporary respite. Though Taeko’s far from the noise of the city, the questions of marriage and of motherhood once again encroach upon her and interrupt the slowed pace of a summertime self-discovery. One night at the farm, the family corners Taeko with talk of marrying Toshio—a man she’s only known for weeks. Despite feeling some attraction to Toshio, their aggressive persistence that she marry him immediately forces her into the position of a child, disallowed from making her own decisions.

And yet Taeko does take the pushy family up on their offer: as the credits roll, she gets on the train back home, only to suddenly rush for a bus and return to the town, and into Toshio’s open arms. Takahata surrounds the pair with a group of Taeko’s former elementary school classmates, with her ten-year-old self at the center. The screen fades to black and all figures disappear, except for the young Taeko, who now stares wide-eyed (bewildered? overwhelmed? frightened?) at the viewer. This detour, which connects the actualization of the adult to the fulfillment of exactly what the family wanted, hurries a coming-of-age fraught with the fear of falling behind. Twenty-seven, as said by many characters throughout the film (including Toshio), is an age to be married and to have kids, not to be a kid any longer. Taeko, having heard this for all of her adult life, is afraid.

One restless night, I learned of a yoga pose called the “corpse pose,” or the Savasana. The corpse pose requires you to lie on your back and to relax each muscle one at a time—unclench your jaw, loosen your shoulders. I sunk into the mattress. And on the way down, suddenly everything appeared in flashes—where I’d been, where I’d go, who said what and how it made me feel. Perhaps Taeko had experienced a similar type of casual ego death when confronted with a lifetime. Maybe that jolt of panic had driven her to chase the fantasy of others even after the credits were rolling and she’d chosen the train, simplifying a gloriously discordant life into a respectable object. —Kelley Dong

Picnic

Kelley, your meditation on Only Yesterday—a film I haven’t seen, but resolve to as soon as I can—inspired me to revisit one of my favorites, and so I thank you for opening our correspondence with a title that surfaced for mea very specific summer saudade feeling. There is always something bittersweet about these torrid months. North of the equator, summer has a very specific connotation: it recalls the very fleeting nature of time, of deeds undone and promises unkept.

Thinking of Taeko, transplanted to the countryside with her anxieties in tow, I vividly recalled Joshua Logan’s Cinemascope adaptation of William Inge’s 1955 drama Picnic. Set on the eve of a small Kansas town’s Labor Day Picnic, the drama takes place over 24 hours—the lifespan of a mayfly, as it so happens—beginning with the arrival of washed-up football star Hal Carson, who hits town on a grain freight in search of an old college pal. His grimy comportment and jittery demeanor mark him from jump as a mysterious outsider, exactly the kind of figure designed to raise Cain in a sleepy berg. Stopping at a nearby boarding house for a quick bath, he meets a trio of women: local belle Madge (Kim Novak), her tomboyish sister Millie (Susan Strasberg), and resident schoolmarm Rosemary (Rosalind Russell)—each of whom will fall in and out of love with the wandering stranger before dawn.

As the day of festivities progress, Hal’s presence changes from welcome novelty to imminent threat. William Holden’s performance as Hal is among his most physical, and the filmmakers use every inch of his splendid, bronze, atypically hairless torso to draw us further into his spell. He’s a harmless enough chap, but his past hides any number of dark secrets—and his proximity, first to Millie as her date to the town picnic, later to the beautiful Madge and the local schoolteacher, incite panic among the locals. This annual festival serves multiple functions for the proud people of this Kansas wheat capital: as a fitting end to a summer of hard labor, a chance to reconnect with one another and blow off long-held steam, and as a kind of pagan ritual to ensure a fruitful harvest come fall. Every year, the picnic committee crowns a “Queen of Neewollah” (“Halloween,” spelled backwards), a prize given to the most beautiful girl in town—and this year, it’s Madge’s turn. In true small-town soap opera fashion, she is betrothed to Hal’s old college friend, Alan Benson (Cliff Robertson), scion of his father’s wheat processing empire and the wealthiest man in town.

Carson’s visit has an ulterior motive: after a decade of trying his luck on the football field and, later, in Hollywood, he’s staring down middle age and tired of wandering. Like any man worth his salt, he wants to make something of himself, and has placed his last shred of hope in his fraternity brother’s hands. Benson assures his old friend that there’s a place for him in the business—as a lowly shoveler, at first, but with enough hard work there will surely be no limit to his success. Across town, Benson’s would-be pride receives a pep talk of a wholly different order. Madge’s mother, abandoned by her own husband shortly after Millie’s birth, hounds her daughter about the importance of her impending marriage—what it could mean for their family and, moreover, how lucky Madge is to have hooked such a prosperous beau. She reiterates, in so many ways, that Madge’s beauty is her finest asset—one that will deliver her from poverty and catapult her into a life of charity balls, country clubs, and charge accounts at all the local stores. “Don’t wait,” she chides, again and again. “This summer you’re nineteen, next summer you’ll be twenty, and soon it will be too late.”

Picnic is four decades behind and 6,000 miles away from the drama of Only Yesterday, but the bittersweetness of the summer months beats hard and fast within their respective cores. The cycle of planting and sowing, and patiently waiting through sultry heat for the fruits of one’s labor, connects Taeko’s youth and Madge’s beauty across time, space, and style. At 27, Taeko is at a crucial juncture in her own life—one that, depending on her decision, could yield a lifetime of happiness or an old age spent in isolation. The tenuousness of Madge’s teenaged vitality is her greatest asset, and in Hal we see a rare glimpse of the male equivalent.

Hal’s a charming roué, and his days are numbered; the burden of misspent expectation weighs on his body as heavily as the fine lines on a woman’s face. Dropped into a tight-knit community at the end of his tether, Hal sees two paths before him: to conform, settle down, and make something of himself, or to buck the conventions of his forebears and continue into the unknown. For Madge, whose young life has only known conformity and ritual, Hal’s masculine allure promises danger and adventure. I’ll spare you the precise plot details that throw these yearning, lovelorn loners together, as they are among the most beautiful moments I’ve encountered on screen. Know only that the moment of reckoning that transpires between them is no tormented summer storm: instead they share something like a warm breeze, the kind that whispers through a field after days of long, hot stillness. —Caroline Golum

Reverse Shot is a publication of Museum of the Moving Image. Join us at the Museum for our weekly virtual Reverse Shot Happy Hour, every Friday at 5:00 p.m.