Every Halloween, we present a week’s worth of perfect holiday programming.

First Night:

The Invitation

Certainty is terrifying. As human beings we’re not meant to be secure in our knowledge of who we are, what we are, why we are. By design, it seems, we’re fumbling creatures scattered about this darkling plain, left to fend for ourselves, inside our own heads. This makes us susceptible to those who dangle the possibility of certainty—the evangelicals and the political charlatans, the impresarios of doom, the pied pipers only out for themselves. We’re living through a particularly scary moment in American history because our elected high priest disavows nuance, views dissent as his enemy, and manipulates his leagues of followers into not only believing lies but also inherently devaluing truth. And even though he has proven time and again to have no convictions, he still preaches the gospel of certainty.

It feels disingenuous to open our annual Halloween-week horror movie tradition—in which we meditate on what scares us—without acknowledging our waking political nightmare. It’s way past “bad news”: it has infected our consciousness. This monster preys upon weakness and insecurity, just like so many of our movie villains, whether it’s someone as savvy and craven as A Face in the Crowd’s Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes or mindless and shark-like as Halloween’s Michael Myers. For the rational and compassionate among us, it’s galling to suddenly be confronted with the fact that so much of the country has been led into what is essentially a large-scale cult.

Though it debuted about 18 months before the 2016 election, Karyn Kusama’s sinister, rattling The Invitation gets at the tenor of contemporary American life better than any other recent horror film. Our daily news cycle and the resulting, tirelessly reductive cultural conversation can make you feel like you’ve been trapped at an endless dinner party you regret attending. The Invitation imagines a wine-glass-clutching gathering of L.A. bourgeois as a locus of terror, without falling back on easy satire. Kusama’s film is emotionally keyed into the human fragility that makes us all vulnerable to evil, and is precise about how grief can be used and exploited to nefarious ends. Like a more genre-focused variation on Todd Haynes’s Safe, the film finds the horror in the margins of the wellness industry and identifies the point where self-help becomes a destructive end in itself.

With its elegantly appointed circle of gorgeous thirty-somethings, the dinner party in The Invitation, which we experience through the eyes of long-suffering Will (Logan Marshall-Green), is off-kilter from the start. Will has returned for the first time in two years to his former house, where his ex-wife, Eden (Tammy Blanchard), now lives with her new, recovered-addict boyfriend, David (Michiel Huisman). Eden and David have invited Will and his girlfriend, Kira (Emayatzy Corinealdi), for a special if mysteriously motivated evening, along with an extended group of their closest friends, a perfectly multi-cultural, gay-straight alliance of folks who seem comfortable with one another and eminently in touch with their feelings. Eden, however, moving ethereally across the hardwood floors of her sleek, modernist home in a clingy white dress that looks like a cross between a bridal gown and a death shroud, immediately sets the tone of the night off; at the same time, everyone treats her like she’s a recuperating invalid, explaining away her odd behavior as though part of some unspoken healing process. Making matters stranger is that Eden and David have also invited the ragged wild-child Sadie (Lindsay Burdge) and the hulking Pruitt (John Carroll Lynch), strangers to everyone else whom the couple met as fellow disciples on a self-help retreat in Mexico.

Kusama and screenwriters Phil Hay and Matt Manfredi initially have fun with the conceit: “Yeah, they’re a little weird, but this is L.A—they’re harmless,” shrugs friend Tommy (Mike Doyle). Yet the film only works as well as it does because it takes the grief of its characters seriously. It gradually becomes clear, through effectively placed flashbacks, that Eden and Will lost a young son years earlier. Will’s response has been to retreat into himself, hold on to his anger and bitterness, and distrust emotional connection; Eden, on the other hand, has been on a spiritual journey to cleanse herself of agony and ascend to enlightenment. “I’m free. All that useless pain is gone,” she claims to Will, though her trembling lips and ever-downcast eyes tell a different story. Even after the party atmosphere is irrevocably tainted by David and Eden screening for the group a very non-celebratory video that seems to show a sick woman being guided gently to death, most of the guests stick around, laughing off their uneasiness, forcing polite conversation out of friendly obligation, and happily gulping “ridiculously expensive” wine. As the night wears on, Will becomes increasingly convinced that they have been summoned here for some horrible purpose. Marshall-Green superbly centers the film with anxiety-intensifying reaction shots of extreme suspicion; he is equally effective as he begins to zero in on what’s going on and when he begins to doubt his own senses, led to believe his fears that something is very wrong are all in his head.

Kusama excels at navigating this tricky territory, at rendering those fuzzy moments when casual chitchat has segued into nerve-wracking anxiety. When The Invitation finally gives in to all-out horror—with stabbings, gunshots, and bludgeonings—it’s both a major relief, because the characters no longer have to plaster smiles on their faces, and dramatically disappointing: the tension has been so superbly wrought one is almost sad to see it drain away. The scariest thing about The Invitation is the desperation with which Eden and David feel driven to carry out their mission, and their certainty that they are right. And if their guests can’t be convinced of their moral and spiritual righteousness, then they are determined to take them down.

In her attempt to deny her own grief, Eden has expunged her humanity. But she’s hardly anomalous: in the film’s chilling punch line, we realize that there are a lot more lost souls out there—throughout the L.A. hills but surely far beyond as well—willing to punish the world for their own unhappiness. We’ve all been invited to this party, haven’t we? —MK

Second Night:

The Ghost Train

A remote railway station in Cornwall after dark. On one side of the station runs the line from London to the coast. On the other side, an abandoned track: the site of a tragedy decades before, when a swing-bridge was left open and a full passenger train drove into the water. This second line leads nowhere. A group of passengers—trapped in the station for the night—is told by a station master about a “ghost train,” which is said to pass through the station on the abandoned line and whose apparition means death for all who set eyes on it.

The Ghost Train, from 1941, is terrifying, very much despite itself. Based on a 1920s British stage play (much given, twice filmed in the silent era but never completed) and produced in the classic Gainsborough Pictures tradition (of Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes), it presents throughout as a light comedy vehicle, the original play having been altered by writer Val Guest (later a director for Hammer) to incorporate diminutive vaudeville comedian Arthur Askey’s routines into the narrative. What results, from a 2018 perspective, is a film that seems to be wrestling with its own components. It offers a stagebound suspense potboiler, a popular but now hugely dated comic turn, and a barnstorming horror concept all mixed together for the purpose of raising British morale during World War II. The ingeniousness of the play’s storytelling and the ease with which the highly skilled filmmakers tap into traditional superstitions and anxieties make the horror aspects effortlessly effective, while the comedy both purposefully detracts from—yet unwittingly augments—the sense of dread. What comes across most strongly is the film’s aching determination not to be too scary. It fails.

In a clear nod to Maupassant via John Ford’s Stagecoach (the characters are archetypes from every level of British society; almost all have secrets; the doctor is a drunk), these very disparate people spend the duration of the film in one place, while a storm rages outside, with only fear and confusion lying between them and the dawn. They are visited by a beautiful, haunted woman (The Lady Vanishes’ Linden Travers) who is determined to stay with them, so she can see the Ghost Train; then by a man who has come to fetch her because he understandably fears for her mental health. Soon enough, the Ghost Train does indeed come. And as promised, death follows along with it.

Imagine if Suspiria featured a Hawaiian-shirted Robin Williams as himself, taking up 40% of the film’s screen time riffing like a jack-in-the-box about anything and everything, and you get a slight sense of the peculiarity of The Ghost Train. In its bizarre tonality there is something of the knowing hoax, which is in keeping with the plot. Of the eleven characters presented, six are not who they seem. Among them are one undercover detective, one MI5 agent, and four Fifth Column Nazi gunrunners. The Ghost Train itself is nothing of the kind, it is all too real. But even if half of the characters are only pretending to be frightened, that doesn’t spare the audience. When the tension mounts and the screen darkens, we are almost taken by surprise that something so frivolous can turn on us so quickly, in an instant of confusion and fear. Askey is wisely pushed aside during all the climaxes, yet reappears immediately after most of them, lest the tension be too oppressive for wartime audiences.

I first saw the play in an amateur production in the late 1970s and what struck me was the noise. While a jump scare can feature a bang or a monstrous shriek, traditionally the loudest prolonged sound in a ghost story is the scream of the prey. But there is nothing that builds, aurally, quite like the arrival of a fast train and the cacophony of it bellowing past a station without slowing down, its deafening whistle and the cry of Linden Travers’s cursed victim piling screams upon screams. The Ghost Train delivers this sensation twice, with a very different context each time. Jokes may not be as funny when we’ve heard them before, a thriller may not thrill quite so much when we know the ending, but as we all know, if something is scary, we can watch it again and again. —JA

Third Night:

The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane

“Aren’t you scared?” The question is earnest, while the context is mesmerizingly odd. It’s asked by one teenage misfit, Mario, an aspiring magician left with a limp from a bout with polio, of another, Rynn, a precocious 13-year-old who always seems to be alone in her secluded colonial house, and whose unseen father is the talk of her unnamed small town. While Mario is played by Scott Jacoby, whose career is predominantly couched within the realm of 1970s television, Rynn is far more conspicuously played by Jodie Foster in one of her first starring roles, overshadowed by her turn in Taxi Driver later that year. Even at 14, Foster brings a stolid self-assurance to Rynn that almost makes you forget to ask whether or not she would, or should, be frightened by a naturally unnerving situation: living all by herself in a house in the woods; cordially offering tea to guests and excuses for why her father, a poet she insists is cloistered in the study upstairs, is unable to greet them; visited and revisited by a vindictive landlady and her lecherous son.

The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane doesn’t derive its biggest chills from the mystery of Rynn’s father’s unexplained absence, but from questions of what might happen to her next. Although it was marketed as a horror film when it was released in 1976, it’s not the Bad Seed-indebted slasher movie implied by its poster; instead, it turns that premise inside out, more wary of latent threats that might materialize at Rynn’s doorstep. This home, this demeanor, and this gentility come to seem relatively straightforward, a defense against the creepy, and often downright menacing figures that might invade. By taking Rynn’s plight seriously, director Nicolas Gessner imparts emotional honesty to a film that may otherwise appear a campy mid-’70s curio. Certain circumstances of production give it the feel of a forgotten, even repressed memory: it was filmed in Quebec shortly after the 1974 announcement of a government tax cut for local productions, and its limited range of sets, hokey special effects, and dated slap bass disco fills often make it seem like it was made for TV. In addition to Foster, the film also features a startling presence in Martin Sheen as a child predator, a queasy open secret in the town; it’s likely that his family’s fortune and influence helped to quiet any rumors (his mother, Mrs. Hallet, also happens to be Rynn’s landlady). Watching Sheen circle Foster in a film that one might gloss over in their respective filmographies instills an uncanny sensation, like driving off-road. He wriggles his way through the front door into Rynn’s living room on Halloween night, also her 13th birthday, and, nearly twice her height, he swaggers around the space with a threatening physicality. She holds her own, but Rynn’s self-possession contrasts with the inescapable vulnerability of her age and stature.

Setting is both abstract and not: ambiguously northeastern, right after the final leaves have fallen and left behind a frigid thicket of branches. For the benefit of the tax shelter, there are moments where Quebec is implied; after she discovers Rynn using an instructional record to teach herself Hebrew, Mrs. Hallet suggests that French would be more practical to learn. Yet there are several more moments that suggest chilly, parochial New England, which sharpens the story’s historical and cultural subtext. As one of the first Mayflower-era families to settle the town, the Hallets are malicious and openly racist toward newer residents. Rynn and her father are a few months into a three-year rental of one of Mrs. Hallet’s houses, and Mrs. Hallet threatens to evict them due to the irregularity of their domestic setup, fixating on the poet’s absence, and on edge because of Rynn’s independence. Supporting characters continually remind Rynn of what she should be doing—going to school, or keeping up with the football team—but skeptical of groupthink, Rynn insists to Mario that “school is stultifying.” While riding the bus into town, she reads Emily Dickinson, which conjures up a distinctly New England strain of individualism: a fight to the death against conformity that’s contingent upon a self-preserving, yet lonely, isolation.

All the same, one still wonders what secrets might lurk beneath Rynn’s practical exterior, and exactly where her father might be—and why she’s so protective of whatever she keeps in her cellar. It’s not long before we see Rynn dispose of a body while wearing a Norman Bates-esque straight face, no matter whether or not it was an accidental death. Playing off a genre that so frequently associates demonic presence with solitary little girls, The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane isn’t concerned with twisting Rynn’s innocence to sensationalize, but rather her ability to wield her autonomy as a shield against the world. Even her relationship with the clearly late-teenage Mario turns a bit sinister with the implication of intimacy, kept largely off-screen. The film concludes with a close-up of Rynn in front of a crackling fireplace, watching Sheen choke to death after poisoning his tea in self-defense. She’s serious, collected, but clearly rattled; she seems to reckon with the solitary life of survival stretching out endlessly ahead. —CL

Fourth Night:

The Creature from the Black Lagoon

“In the beginning, God created the Heaven and the Earth,” goes the opening narration to The Creature from the Black Lagoon, grandly invoking no less than the Book of Genesis to frame its tale of an ichthyological expedition to a secluded stretch of the Amazon—a “paradise” untouched by millennia of climate change, man-made or otherwise. “And I thought the Mississippi was something,” sighs Kay Lawrence (Julia Adams), betraying the country-girl roots beneath a finishing-school exterior (not a kerchief out of place) and innocently exacerbating the gap between ancient and modern and Old and New Worlds implicit in the story’s adventure-saga setup and science-versus-superstition subtext.

Kay is on hand as arm candy to lungfish expert Dr. David Reed (Richard Carlson), whose laboratory-stoked stoicism is not shaken by the prehistoric grandeur of the setting, nor the appearance, several days in, of a gilled, predatory humanoid. Where the boat’s superstitious navigator (Nestor Pavia) sees a “demon,” Dr. Reed perceives a momentous discovery, and acts dispassionately—right up until the Creature makes a move on his girl, at which point he transforms from a man of science into a man of action, taking up a speargun and diving into the murky waters of the black lagoon.

Such hokey B-movie particulars, combined with some wooden acting and a lack of a globally acknowledged classic literary source, help to explain why The Creature from the Black Lagoon has long been relegated to the second tier of Universal monster movies. By 1954, the studio that loosed Dracula, Frankenstein and the Wolf Man on the world had mostly defanged and declawed their creations, licensing them out for adventures with Abbott and Costello and piling up superfluous sequels. Upon its release, the film, directed by Jack Arnold from a script by Harry Essex and Arthur A. Ross (though the idea originated with producer William Alland after he heard an anecdote at a dinner party on the set of Citizen Kane), was more notable for the 3D gimmickry underwriting its exhibition than for any real sense of terror, and I’d say that despite the blaring, Bernard Herrmann-esque music cues by Henry Mancini (which are very Cape Fear, a decade before the fact) the film isn’t especially scary or unnerving, lacking the paranoid menace of Arnold’s earlier It Came From Outer Space (1953) or the intensity of his subsequent The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957).

What it does have, though—and what Guillermo del Toro was responding to when he resurrected the Creature for last year’s Oscar-winning The Shape of Water—is a sort of primordial lyricism that nearly lives up to its mythic opening voiceover. On board the tramp steamer Rita, hunkered down with the various members of its square-jawed ensemble, The Creature from the Black Lagoon is stolid stuff, but when the camera descends into the depths, it’s got an eerie, spectral beauty somewhere between the swimming pool scene in Cat People (1942) and the zoological studies of Jean Painlevé. The image of the Creature (played underwater by stuntman Ricou Browning) backstroking in hidden sync with Kay’s graceful front crawl is haunting and melancholy, and while del Toro’s childhood desire to remake the movie from its ostensible villain’s desirous point of view makes sense, it also banally literalizes the carefully coded, complicitous sympathy that already exists in Arnold’s vision, mediated by the rubbery phoniness of the film’s namesake, who lacks the more soulful anthropomorphism of figures like Boris Karloff’s Monster.

The complex, waterlogged eroticism on display in these scenes would bloom more fully in Psycho’s shower scene and the prologue to Jaws (1975), which owes plenty of debts (including the hunting-party rhythms of its second half) and whose success two decades later marked the resurrection of Universal’s horror-movie brand. As fuel for the imagination of genre masters to come, The Creature from the Black Lagoon is potent stuff, right up to a climax that’s a bit cluttered in its staging and geography but grants the gill-man a lonely, tragic majesty that filters Old Testament severity through human sentiment: not quite ashes-to-ashes-to-dust, but a return to whence he came all the same. —AN

Fifth Night:

A Scary Time

Shirley Clarke’s 1960 short film A Scary Time was commissioned by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and one wonders if the final result was exactly what they had in mind. As the film begins, its pairing of loose vérité images with scripted voiceover recalls Clarke’s Academy Award–nominated short Skyscraper (also completed in 1960, documenting the construction of the now-infamous structure at 666 Fifth Avenue owned by the Kushner family), swapping images of hefty hard-hatted workers coupled with gruff Noo Yawk babble for images of children in Connecticut preparing to make mischief on Halloween overlaid with disarming, unaffected Peanuts-esque (though the film pre-dates Great Pumpkin) chatter.

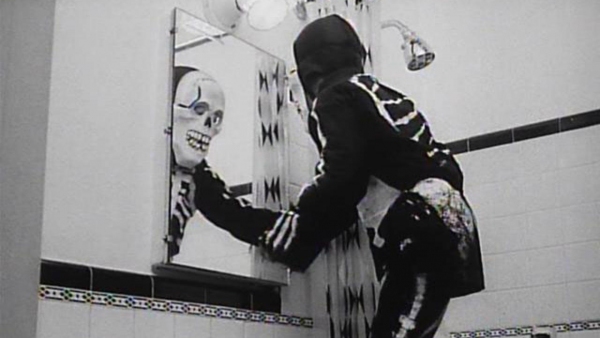

All seems normal in the film’s first few minutes. The kids are adorable (one is D.A. Pennebaker’s son Frazer), and Clarke’s camera observes them readying their costumes and gleefully heading out into the night to attend a bonfire bacchanal, which in its mixture of innocence and dangerously unbridled youthful energy recalls the famous Halloween sequence of Meet Me in St. Louis. As the kids cavort around the fire, Clarke’s cutting, from close-ups of contorted masks and flickering flames to more abstract shots capturing bits and pieces of the wild ones in motion, suggests her faculty with filming dance seen in her earlier shorts A Moment in Love and Dance in the Sun. The scene is eerie and potent—maybe something actually bad will happen—but Clarke only ramps the film’s intensity up from here.

In a moment, the mood grows darker: Clarke cuts from a bawling infant observing the mayhem to another weeping child, one who is not white, and is clearly not celebrating Halloween along with these kids from Norfolk, Connecticut. A stream of similar images of distressed brown and black faces follows; if the point of this interlude isn’t immediately clear, Clarke will make it so as she continues to juxtapose field footage from the regions where UNICEF works with these scenes of suburban American kids tricking and treating. Watch as the children in Connecticut wreck property, waste a whole bag of flour on a prank gone awry, or simply reject food outright, and then look at images of children who would be grateful for the most meager of scraps. Clarke’s critique does grant the Connecticut gang redemption, however, in the film’s final movement, turning them from wanton roving revelers into costumed ambassadors raising small change to help support UNICEF’s work as they make their Halloween rounds.

A Scary Time might well rank as one of the oddest pairings on record between a mainstream NGO and filmmaker. It’s a Shirley Clarke film through and through; anyone familiar with her body of work will recognize an unforced intimacy with her subjects, the musicality of her editing choices and camera movements, the overall improvisational feel masking design and intent. Yet as strange as the film may be, it stays on message. As young Peter the Skeleton drifts off to sleep in the comfort of his safe upper-middle-class enclave, he counts off: “One penny helps one child live…two pennies help two children live…three pennies help…” and so on. As violins screech on the soundtrack, Clarke shock-cuts again, here to a young child’s face covered in flies. Haunted by the images bouncing around his mind, Peter cries out, “Help, mommy, daddy, make it stop. Make it stop!” And the film cuts to black, leveling the viewer. The introduction of such bold aesthetic choices into something we’d today likely dismiss as “branded content” is a reminder of what we’ve come to learn about Shirley Clarke in the recent years of restorations and re-releases of her work: she was a truly fearsome talent. —JR

Sixth Night:

Messiah of Evil

An unholy—truly—mix of L.A. noir, social satire, and gross-out horror, Messiah of Evil (1973), codirected by husband-and-wife duo Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, is an understandably misunderstood, largely forgotten oddity of the seventies. Its greatest claim to fame may be the aggressive set design by a young Jack Fisk, but Messiah of Evil is an all-around surprising descent into cheapo hell that deserves a wider cult. It plays now like a cannibalistic variation on Inherent Vice—it’s as funny-scary as that sounds, and half as slick. At any point, the film feels like it could choose a different rabbit hole to go down, leaving its viewers to wonder what’s around the next corner but also what the hell just happened. Desolate cityscapes are common to surreally tinged horror movies (The Seventh Victim, Carnival of Souls), but these disquieting L.A. locales have a particularly vivid, specific flavor, turning a layabout artists’ bohemia into a site of supernatural carnage.

A brief, seemingly disconnected prologue sets the jagged art-pop tone: to the disjunctive tune of eerie, minor-key ballad "Hold on to Love," sung by folk soprano Raun MacKinnon, a man is cradled beatifically by a young girl before she takes out a straight razor and slashes his throat. We then flash to a blindingly sun-drenched institutional hallway where a woman, her face obscured by light, is nearly crawling the walls as she moves toward the static camera. It is this haunted woman, Arletty (Marianna Hill), who becomes our narrator, telling us about the “neon stucco towns” in which “no one will hear you scream” (naturally this would become the film’s poster tagline). The place she’s talking about, we soon learn in a flashback, is California’s small coastal Point Dune, where her painter father Joseph has been living, and into which he has now apparently disappeared. Summoned there by his increasingly strange and ominous letters laced with doomsday prophecy, Arletty soon becomes involved with a group of her father’s acquaintances, the dandyish collector Thom (Michael Greer) and his two female hangers-on, Laura (Anitra Ford) and Toni (Joy Bang). The lackadaisical nature of these wayward souls, and the lack of urgency with which they conduct their lives and follow their unambitious pursuits, makes for an initially meandering horror film, kind of like a hangout movie about artists and models and dealers punctuated by bursts of paint and blood.

What exactly is wrong with Point Dune? Like Bodega or Antonio Bay, quite a lot, but it’s hard to define at first. It’s just a “piss-poor little town, deader than hell,” according to a doomed gas station attendant Arletty meets en route. He’s right, but the dead don’t stay quiet, as they say. Reliably terrified character actor Elisha Cook Jr. turns up as a tattered local who claims to know Joseph, but his advice to Arletty about her dad isn’t promising: “You've got to burn him, set fire to his body...don't put him in the ground.” There are warnings about a “blood moon,” a found diary tells of "pale women with shadowy eyes," and the voiceover narration is peppered with I-think-I-get-it lines like, “My father said you’re about to awaken when you dream that you’re dreaming.”

The reason for all this overbearing ominousness has something to do with a hundred-year-old curse and the Donner Party, resulting in an evil contagion that turns locals into ravenous zombies, and Joseph seems to be infected. All this is really beside the point for a film memorable for its visual élan and disquieting horror set pieces. When Arletty first descends into her father’s abandoned beachside house, she flicks on the light, revealing walls completely covered in trompe l’oeil murals, of escalators and dark figures and one man posed like Rod Serling—an indulgent pop art twilight zone. Beyond Fisk’s overwhelming set design, Huyck and Katz prove their horror mettle during two ingeniously staged scare scenes. In the first, Laura—freaked out by a rat-munching, cross-eyed creep with whom she mistakenly hitches a ride while trying to get out of Point Dune—seeks refuge in a supermarket, only to be overcome by a mass of hungry, zombified consumers; it’s a slow-building scene, moving to Laura’s dreamy, heel-clicking rhythms, and occurring so gradually that it takes a moment to register that she is suddenly being eaten alive to the echoey strains of sax-y Muzak.

“Laura, leave me some dope” is the final thing Toni says to Laura before she splits, a wasted, unceremonious goodbye for a character who meets a sticky end. But Toni’s farewell is even more chilling, and makes for the film’s most Hitchcockian sequence. Toni enters a desolate movie theater under a marquee boasting something unpromisingly titled Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye. (Four years later, Messiah of Evil would turn up as its own marquee joke in Annie Hall, glimpsed in passing as a title on an L.A. movie theater, presumably to illustrate the cultural barrenness of the city in juxtaposition to, say, New York rep house picks like The Sorrow and the Pity.) After taking her seat in the theater, amidst a sea of faded-red upholstered chairs, Toni becomes so engrossed in the truly strange audiovisual mash-up on the screen (it seems to be a compilation of violent westerns and action films) that she doesn’t notice as the once near-empty theater has begun filling up. Every time it cuts back there are more and more pale-faced strangers in the rows in back of her, like the crows amassing behind Tippi Hedren in The Birds. Only when she sees two figures with bleeding eyes, one on each side of her row, does she try—and fail—to escape.

Messiah of Evil would be the only film Huyck and the uncredited Katz would direct together, though as a screenwriting team—and as George Lucas’s professional acquaintances—they would be able to bring their penchant for disreputable gonzo gore and low-end gags to bigger offerings like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Howard the Duck, movies that felt dirty and cheap despite their high budgets. Conversely, Messiah of Evil (renamed Return of the Living Dead in a 1979 reissue, before that was stopped by George Romero’s legal team) seems somehow elevated and deliberate despite its limitations and cut-rate feel. There’s a detached wisdom here, a lived-in quality that feels of its moment: a decade of violence and dead-ends and disillusionment. The film ends with our narrator relating a hopeful idea: “each of us dying slowly in the prison of our minds.” —MK

Seventh Night:

Panna a netvor

In 1978, Czechoslovak filmmaker Juraj Herz restored to the “Beauty and the Beast” myth its quivering Gothic heart. Panna a netvor, or Virgin and Monster, lays bare the perverse tissue lurking under the skin of a story so often misconstrued as romance—or whose romance is routinely debrided of the inexorable risk, delusion, and self-abnegation of love. “Beauty and the Beast,” at the root, is a rape fantasy buried in a marriage plot, or vice versa, depending on the teller. Our chaste heroine, here named Julie (Zdena Studenková), is isolated from family and friends, and coerced into captivity, where she is groomed to find her thorny plight not only tolerable but irresistible. Panna a netvor pulses with a menace and cruelty rare in renderings of the tale. To tremble with love we must first pass through fear.

Herz, who died this year, filmed horror with a deft and familiar hand. Born in an atheist-Jewish home in 1934, he was shunted to Ravensbrück, despite an eleventh-hour baptism, at ten years old. It is hard not to see in his life someone who acclimated to the grotesque out of pure need, and who never shook its grip. Years later, referring to a set of morbid anatomical models in his black comedy The Cremator (1969), Herz laughed: “Only I felt good in there, naturally.” Directing lent a framework to his fixations. He excelled at scratching gilded surfaces to reach the rot beneath: the luetic officers of Oil Lamps (1971), the corrupt corporation of Ferat Vampire (1982), the feckless rulers of The Ninth Heart (1979). It’s fitting that his memoir, still not translated into English, is titled Autopsy, a medical procedure undertaken when an affliction is not inscribed on the visible body, when the eyes alone cannot be trusted.

Panna a netvor, of course, is a film of shifting appearances. Hirsute Jean Marais, of Cocteau’s La belle et la bête (1946), and Disney’s cravat-clad creatures (1991 and 2017) exude leonine elegance and a kind of noble despair at their fates. But the atavistic netvor (Vlastimil Harapes) is truly repulsive, with his haggard bird head, tattered cape and feathers, filth-matted claws, seesaw gait, and diet of virginal blood. And yet for half of the film we do not even see his face. (Neither does Julie, a bargain that, unlike Bluebeard’s wife, she keeps.) Instead, cinematographer Jirí Macháne’s camera glides up trees and creeps around corners, forcing us to inhabit the lurking perspective of the voyeur, often without our awareness, as he hunts his prey (a peasant woman) or stalks Julie (too innocent—and bourgeois—to consume) around a crumbling castle with the bleak air of a charnel house. Frenzied organ tremolos sustain the droning tension of these sequences, imbued with an ambient threat of sexual violation—but also an aching, unbearable tenderness as the netvor squirms under the focused sincerity of Julie’s developing love and erotic curiosity.

Dread ripples through the workaday as well, producing indelible images: butchered pigs at a wedding feast, porcelain rattling over a mist-shrouded waterfall, a smashed mug of milk, a purloined gown fraying before our eyes into mere rags. Nothing is free from a feeling of cosmic portent. Space and time do nothing to guard against violence: when the netvor rends an oil painting of Julie’s late mother, we cut to Julie (who is said to be her eerie spitting image) lifting her luminous face in shock, despite the dense thicket of forest between them. These frequent frontal compositions, where characters’ eyes meet the camera, hint at Herz’s theater training—he studied puppetry at FAMU and collaborated with Jan Švankmajer—but they also lend the whole affair an uncanny unreality.

Most inscrutable is one image that recurs twice: first Julie, drugged into a fitful slumber for a rape the beast never commits, dreams of a man carrying a woman, as if over a marital threshold, through a flickering corridor where endless doors open before them. Composer Petr Hapka’s saccharine score swells deliriously. It is a virginal vision of ecstatic romance, where the humanized monster is her dashing rescuer. But a near-identical shot appears when our beast is tamed into his human form. Or is he? Earlier the monster broods: “Every woman has the power to make beautiful the man she loves.” Has the netvor transformed, or is Julie sunk in self-delusion? And isn’t self-delusion another word for love? Panna a netvor is sly enough to stage love and marriage as horrors from which the sufferers, as Julie herself wishes aloud, "never wake up.” —CD