Every Halloween, we present a week’s worth of perfect holiday programming.

First Night:

The Birds

Dumb, squawking gulls dive-bombing into random passersby. It’s the most apt movie image I can come up with to open the 2017 edition of our annual Halloween horror column, for a current moment in which all has devolved into absurd, dangerous nonsense, and an ever-looming mindless threat hovers over us. No doubt about it, the birdbrains are amassing on our telephone wires and jungle gyms, and we’re holding out as long as we can, putting up the good fight. That may sound overstated, but good horror movies convince us our paranoia is justified, and, for me, watching The Birds again put its essential conflicts—between the human and the primal, the forces of love and the agents of destruction—into newly frightening relief.

Alfred Hitchcock followed up Psycho with The Birds, and the director and savvy-marketer called the latter “the scariest movie I’ve ever made,” knowing full well the former was possibly the scariest movie anyone ever made up to that point. If I disagree with him, that doesn’t mean it’s not a terrifying film, just that it’s predicated on so many destabilizing, audience-alienating ideas that it’s difficult to become completely immersed in it. There’s a provocative distance frequently placed between the viewer and the material, and specifically us and the odd-duck protagonist, which doesn’t exist in most horror stories, predicated as they are on audience identification.

This is one of the many ways Hitchcock’s film deviates from its pit-of-the-stomach-scary source material: Daphne du Maurier’s 1950 short story, written in a spare style with a propulsive forward motion as single-minded and ruthless as its feathered villains. In that story, set largely in one small farm on a desolate peninsula in Southwest England around Cornwall, Nat Hocken, a farmer and war veteran, is desperately trying to safeguard his family against an ever-growing avian threat surrounding his house. It begins with a disturbing but relatively mild incident in which some birds fly into his children’s bedroom during the night; must be changing weather patterns that drove them inside. Every day, the attacks get worse and, as Nat finds out from neighbors, more widespread. As a few days pass, reports come in from around the world, and, as the family battens down the hatches, a sense of despair and hopelessness takes over. Du Maurier’s most lasting central image is one of mind-boggling ominousness, legions of birds swarming and accumulating above the windswept shores: The smudge became a cloud; and the cloud divided again into five other clouds, spreading north, east, south, and west; and then they were not clouds at all but birds.

With its civilian’s-eye view of an unstoppable foe that attacks indiscriminately by air, du Maurier’s “The Birds,” written in 1952, is much more overtly a WWII story than the adaptation. Whereas du Maurier knew it was scarier to leave much to the imagination (“Then he remembered the hawks,” Nat says, mentioning them only once, letting our minds run wild), Hitchcock, picking up where the explicit, pummeling Psycho left off, escalates slow-burning tension into pure action. Forgoing the author’s pruned-down pleasures, Hitchcock’s The Birds, scripted by Evan Hunter in a radical rewrite (Hunter remembers Hitch telling him “we’re throwing away everything but the title”), is a schizoid experience in which an Oedipal triangle plays out rather dispassionately aside the supernatural terror tale. The psychological tensions that define the characters in The Birds are most fascinating for having little to no payoff; this is the film’s central Hitchcockian perversity and perhaps what most connects it to Psycho, which had created all types of conflict for its leading lady only to cruelly jettison her halfway through. To a much lesser degree, Hitchcock unmoors viewers from the beginning of The Birds by the very nature of anchoring its narrative to Tippi Hedren’s prim-and-proper—and more than a smidge antisocial—Melanie Daniels.

Melanie is resolute in her aims (snag Rod Taylor’s hunky Mitch Brennan), even if her motivations and past are cloudy. In obsessively tracking down near-stranger Mitch, she’s like a distaff version of James Stewart’s Scottie Ferguson. She’s opaque, intrusive, and a little rude to most people she meets in Bodega Bay, the northern California coastal town where Mitch lives. She even breaks into Mitch’s house as part of her elaborate cat-and-mouse flirtation. That she comes across as so off-putting is both a byproduct of Hedren’s ice-queen demeanor and a natural outgrowth of a strange narrative in which she forces herself upon Mitch’s entire family, to the clear chagrin of his widowed mom Lydia (Jessica Tandy), whose withering stares would make any other intruder run for the hills. Doomed local schoolteacher Annie Hayworth, played by sultry brunette Suzanne Pleshette, would seem to be the foil to blonde Melanie, but she’s a red herring of an antagonist—the real third in this love triangle is Lydia, who clings like a barnacle to her son. (Hedren’s recent revelations about Hitchcock’s harassment and mistreatment of her on the set and the vice-like grip he maintained on her subsequent film career adds further disturbing dimensions to the way she’s represented onscreen; and I must admit I’ve always found it an oddly punishing editing choice to use a take in which Hedren flubs a line in her very first dialogue scene…)

Melanie does the bare minimum to win the trust of Lydia, her most successful gesture offering to pick up her young daughter, Cathy (future horror mainstay Veronica Cartwright), from school after Lydia has been traumatized by seeing her neighbor’s freshly picked over corpse, his eyes pecked out by crows. The problem is that trouble and misfortune brew wherever Melanie goes. The moment that Mitch first sees her in Bodega Bay, spying her escaping in the rowboat that brought her to his front door, is when we first see gulls flock into the frame. In a literal sense, everything would point toward Melanie’s presence being completely incidental to the inexplicable aggression of the birds, yet the unification of the film’s two threads is hardly just narrative dovetailing. She’s equated to birds in costuming (flitting in feathery furs and perching on high heels), visual composition (her fingernails become talons when she clutches pencils, plays with telephone chords, or holds cotton to a head wound; her head still and cocked to the side when riding an elevator near the beginning of the film), and dialogue (“Back in your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels”).

The distrust of Melanie reaches its cathartic zenith at the Tides Restaurant, when a high-strung mother of two who has just witnessed the birds wreak havoc, turns irrationally on Melanie: “Who are you? What are you? Where did you come from? I think you’re the cause of all this. I think you’re evil!” The film’s long-puzzled-over terrifying existential question (“Why do the birds attack?”) thus has an even more disconcerting, unanswerable follow-up: “And how is this woman connected to these attacks?” That all this mindless horror might in some way have been initiated by a human being—someone who operates first and foremost under self-interest and never looks back—only makes things scarier. Not that it matters much: all of us, Melanie included, are goners, anyway. —MK

Second Night:

Lake Mungo

Ghosts want only to be seen; Lake Mungo examines our compulsion to meet them face to face. Australian filmmaker Joel Anderson’s first and only feature, which deserves its cult reputation as a high-water mark of the found-footage genre, was considered “lost” following some disappointingly spotty theatrical distribution in 2008. (It is now widely available on streaming platforms, but the only Blu-ray edition in circulation is German.) Of all the mock-doc horror films put into circulation after 1999’s The Blair Witch Project, it does by far the most with the formal and ontological possibilities of the format, embedding several competing levels of authorship within its meticulously designed outer shape as a documentary made for Australian television about the death of a suburban teenage girl and its aftermath.

After 16-year-old Alice drowns on a family trip, her father Russell (David Pledger), mother June (Rosie Traynor), and brother Mathew (Martin Sharpe) are all gutted by grief and refuse to let her go, a collective response related via a series of talking-head interviews. The pretense for the documentary is not the tragic death of a local girl, however. The style and tone of the reportage are closer to what you’d expect in a paranormal exposé, and each of Alice’s family members confesses to feeling haunted in different ways. June describes nightmares of her daughter, standing dripping wet at the foot of the bed; Russell relates his encounter with an apparition that lunged at him out of the dark; and Mathew sets up video cameras throughout the house, capturing what appear to be spectral images of Alice roaming the hallways at night.

Dream, experience, and mediated reality: Anderson weaves together these three levels of “seeing” (subconsciously, through technology, and with one’s own eyes) with a shivery ingenuity. The verbal accounts set up Mathew’s surveillance captures, which are compositionally akin to early-20th-century spirit photography: blurry and undistinguished until you spot the phantom in the frame, after which you can’t take your eyes off of her. Alice’s appearance in these murky, underlit shots is discomfiting—she always looks directly into the camera lens—but also melancholy. She’s simultaneously out of place and where she belongs: her death has rendered her an intruder in her own home.

There is a twist here, and it comes earlier than expected. After this, I had no idea where it would go, partially because it seemed to be blocking its own way toward the sorts of satisfactions we expect from horror movies. But Anderson’s script keeps finding ways to deepen the mystery around Alice’s death and (possible) afterlife by revealing more unexpected image sources, each of which complicates the plot and recontextualizes what we’ve already seen. And then just as the supernatural aspects of the film seem to be receding for good, a first-person cell phone video recording throws us fully and irretrievably into the realm of the irrational.

It’s a truly terrifying sequence: watching it alone in the dark on a laptop, I may or may not have yelped. It also gives Lake Mungo its soul, transforming the story’s structuring absence into a protagonist in a way that feels so epiphanically tragic that it brings to mind the perspectival switch of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992). The highest compliment I can pay to Anderson’s surprisingly frightening and lingeringly sad movie is to say that Alice earns her surname, which I haven’t yet mentioned: it’s Palmer. —AN

Third Night:

Diabolique

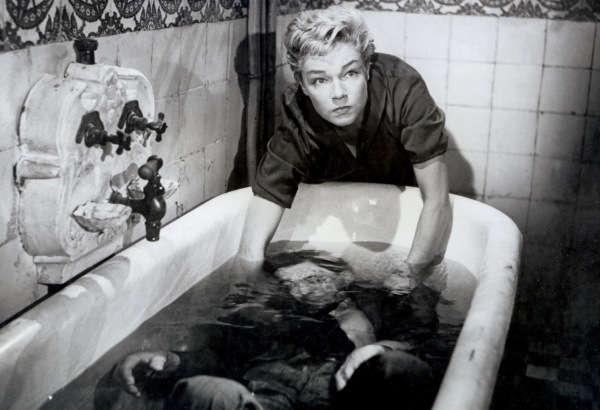

Few filmmakers channeled their cynicism through cinema more effectively than Henri-Georges Clouzot. His brutal, Nazi-financed social satire Le Corbeau, which depicts France as a nation of hypocritical, backstabbing vermin, might just pip Hitchcock’s Vertigo as the nastiest great film ever made. And Vertigo itself owes its existence to Diabolique, a screenplay Hitchcock was so vexed to miss out on (Clouzot beat him to the rights by a matter of hours) that he demanded its writers, Boileau-Narcejac, write one for him as consolation. But there is a world of difference between Clouzot and Hitchcock, not least that Clouzot never gave the impression of finding any of it fun. Even Hitch couldn’t have made Diabolique this grotty, and he wouldn’t have wanted to. Everything and everyone in this film is in the gutter. The awful prep school it’s set in, which resembles a prison camp; the kids, the staff, and especially Paul Meurisse, an actor of immense renown and magnetism who seems to have flicked a switch to extinguish the natural twinkle in his eye. He’s the sadistic headmaster who tortures his young wife (Véra Clouzot) by parading his mistress (Simone Signoret) in front of her. The wife and mistress team up to dispose of Meurisse by drowning him, then dumping his corpse in the school swimming pool to make it resemble accident or suicide, only for the body to disappear the next morning. (Fans of the Gottman Method of marriage-counseling might be interested to learn that it was Véra Clouzot who first lobbied her husband to make Diabolique and to cast her as the put-upon wife, because—according to a close friend—she wanted people to think he had forced her to be in it.)

Clouzot had made his name directing L’assassin habite au 21 (1942) and Quai des Orfèvres (1947), “polars,” short for policiers—detective thrillers—of which Diabolique is also unquestionably one. But if the frisson of the disappearing body is partly explainable as a thriller trope, a sense of the bizarre infects this film from early on (the suit Meurisse is wearing when he drowns is returned by the dry cleaners, to the women’s horror). But what ultimately thrusts Diabolique squarely into a Halloween collection such as this one? Alex Cox put it best when he introduced the film for the BBC’s “Moviedrome” in 1992, pleading with viewers who might be put off by subtitles to persevere: “Tonight’s offering is a horror film. And it’s really frightening. If you watch Diabolique all the way till the end, you will be scared. Guaranteed.”

The climax of the film is indeed what haunts. It is not just the culmination of an exquisite exercise in gossamer-fine thriller plotting, but a rare example of a scenario delivering three impact shocks in immediate succession (an apparition, a murder, and a reveal): an assaultive, almost absurdly complex gamble by Clouzot. Yet the mise-en-scène of that crucial sequence is so magisterial that it freezes the blood. It represents a key moment in horror cinema because it shouldn’t work at all—it is too marionettish, too bold—but does. Perhaps its secret weapon is the carefully knotted atmosphere of deep misanthropy that builds up through the film’s duration and precludes any possibility of ridicule. Or perhaps it is the revelation itself, seconds after the scare, which dissolves away the supernatural to reveal a bleakly rational malevolence. We are left open-mouthed with disbelief and, in default of immediate explanation, terror. As we begin to process the violence, the film sends us hurtling back to reality, piling a different kind of horror onto the first.

Diabolique cannot date because the grubby, shabby evil it depicts will never go away. And there’s a reason why horror was there at the outset of cinema and why it’ll still be there at the end. Because it trades in one of the essential oils of cinema: insecurity. All images can lie, and most images do. With coups de théâtre it pays to watch as carefully as possible after the fireworks have stopped. Columbo-esque detective Charles Vanel (the sardonic trucker of The Wages of Fear and the public defender of Brigitte Bardot’s awful truth in La Vérité) is never more Clouzot’s alter ego than here. He has worked out the plot, but his intervention comes too late, arriving only to catch the culprits, a meager consolation. Vanel stands, like Clouzot, in contemplation of the sleaziest, most diabolical human behavior. James Stewart’s character in Rope got a ten-minute monologue; Clouzot grants Vanel one line and a shrug of impotent contempt. Horrible. —JA

Fourth Night:

Dead Ringers

Everything seems chilling from a cursory glance at the Dead Ringers logline: Jeremy Irons plays identical twin gynecologists who surreptitiously sleep with the same women before eventually meeting a drug-fueled demise—and it’s all loosely based on true events. But the film’s horror runs deeper than its narrative surface. Something about this is inextricably linked to the color red. At first, it deliberately accents the cool grays and blues of the twins’ fertility clinic, but it overtakes the image in surgery scenes through the doctors’ deep crimson scrubs. Denise Cronenberg, the film’s costume designer and its director’s sister, dyed the fabrics herself to create their hyperreal appearance—unlike their desaturated surroundings, the red is dangerously loud, aggressively blanketing the operating table and obscuring faces. The color evokes religious robes, as David Cronenberg hoped it might: when a scrub nurse suits up Irons before a procedure, his arms are outstretched as though he’s preparing to execute a divine order. That sense of anticipation makes it all the more disturbing to see the anesthetized patient on the operating table reflected ghostlike across his body, lying prone with legs spread apart, draped in red sheets.

We first meet Beverly and Elliot Mantle as bespectacled nine-year-olds (played by real-life identical twins Jonathan and Nicholas Haley, finishing each other’s sentences with the same voice in a way that is, for a moment, more unsettling than when their characters merge into one actor); they soon progress from precocious kids prodding a plastic uterus like something out of Hasbro’s Operation into Harvard medical students poring over cadavers. In this brief coming-of-age prologue, Cronenberg plays up the twins’ preference for women as test subjects. When they proposition the little girl next door, she rebuffs them with a string of profanities; unfazed, they head home to tinker with their model of female innards. Later, when they go into private practice, their invention of a surgical tool called the “Mantle Retractor” brings them renown, although a med school professor who spots them using it in lab warns that it “might be fine for a cadaver, but it won’t work with a living patient.” As Beverly starts to lose his mind following a series of romantic and professional travails, he begins using the enormous, gold-cast retractor in routine pelvic exams, insisting that the real problem is that the women don’t fit the tools—he can’t see beyond the ideal theoretical procedure dictated by his design. When he commissions his disturbing set of gynecological tools, resembling alien pincers more than medical probes, they’re designed for “mutant women”: and when a mutation implies anyone who isn’t his twin, they’re weapons to mangle any exterior threat to their closed system.

In a Ballardian perversion of medical practice, the Mantles see bodies as fields of experimentation rather than human beings, including their own. Irons and Irons are at their creepiest when their complementary personal differences start to dissolve—initially, Elliot is the outgoing, donor-courting face of the practice, while Beverly slaves over data collection, but as drugs and detoxes cloud the matter, their oblique references to a shared nervous system seem increasingly plausible. This all begins to feel predestined: Beverly’s identity crisis stems from the fear that one twin may not be anything without the other, and his total emotional dependency on his brother is exposed by the developing relationship with actress Claire Niveau (Geneviève Bujold), which threatens to rupture that dynamic. They retreat from the outside world into their hermetically sealed, modernist apartment, fully stocked with medical texts that foreshadow their ultimate desire to “ease into research.” There’s something indescribably terrifying about that vague aside from Elliot, as it opens up numerous potential links between their medical philosophies and interests in psychologically manipulating bodies. Their synchronized bender, though, is probably their magnum opus.

With Dead Ringers, Cronenberg broke from his already trademark brand of stretchy, gooey, practical effects–aided body horror, opting instead for a more clinical approach (though he couldn’t resist a dream sequence in which Claire bites into a fleshy, pulpy web conjoining the twins). Cronenberg exposes us to each incident as though we, too, are collecting data, privileging us to an uncomfortable level of character detail. There are no cheap graphic shocks when the Mantles are at work, but in conjunction with our research, that only makes the proceedings more unsettling—close-ups of faces as doctors probe under sheets, or a sea of red scrubs as Beverly asks for a nightmarish custom surgical tool, stir up our imaginations. It’s not what it shows, but what it suggests, that gets under our skin. —CL

Fifth Night:

Island of Lost Souls

Dr. Moreau was a thriving surgeon in London until he ruffled the feathers of polite society when it was discovered he had a penchant for performing vivisection on animals for the purpose of splicing their genes with those of humans. He was forced to resume his experiments on a small, deserted island somewhere well off the coast of Samoa, where his reputation as a “brilliant scientist” or “black-hearted, grave-robbing ghoul” (depending on the commenter) grew almost as rapidly as his inevitable God complex. In H. G. Wells’s 1896 novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, he was drawn as tall, strapping, and vivacious, and his closest visual approximation in the multiple film adaptations is the only slightly too-old Burt Lancaster, in the 1977 go-around. In the troubled 1996 version, mountainous, mostly seated Marlon Brando dons a roomy muumuu to play him. Splitting the difference, poundwise, is Charles Laughton, impishly malevolent and icily fey as a goateed Moreau in Erle C. Kenton’s pre-Code classic Island of Lost Souls, released in 1932, the British actor’s first year in American cinema. That same year he would make a distinct impression working with De Mille, Lubitsch, and James Whale, the latter in another great horror standard, the funny The Old Dark House, in which Laughton plays the well-named blustery, doomed passerby Sir William Porterhouse.

It demoralized Laughton that his relatively slight weight “problem” and un-chiseled features qualified him for so many roles as grotesques in the superficial Hollywood system, but the fact is he excelled at them (and for a long streak he rarely lacked for jobs). He could unveil his inner ham during climaxes, and work his subtle facial and physical magic with the dialogue, as when Moreau experimentally places “panther woman” Lota (Kathleen Burke) in the same room as castaway newcomer Edward Parker (Richard Arlen). Moreau wants his creations to transcend their animal origins and achieve humanity, so he’s curious to see how the “woman” he fashioned out of panther and human genes reacts to a non-threatening male, since he and doctor-henchman Montgomery (Arthur Hohl) only inspire fear. Laughton evokes both Moreau’s sadism and (bi)sexual repression in the way he rubs his sweaty hands together, and then leers hungrily from a side room at the morbid meet-cute. When Parker remarks on the doctor’s facility with a whip, Moreau’s line “I learned how to handle one as a boy in Australia” hints at yet deeper repression, and that he may have been raised in his own House of Pain, the name now given to the operating room in which he performs his ghastly experiments/punishments. The most thematically literal line in the film is Moreau’s rhetorical question to Parker, “Do you know what it means to feel like God?” But Laughton is able to render even this purple prose as a deluded and chilling thirst for violence.

Wells was alive to see this version, and he hated it, supposedly because its pulpiness left little room for the philosophical heft of his book. And how could it have been otherwise? Source novelists are notoriously suspect critics of adaptations of their work, and this film’s screenplay in fact artfully streamlines the novel’s action while retaining as much of the moral thorniness about genetic tampering and what it means to be human as one could reasonably expect from a 71-minute studio film shot mostly on backlots. Co-writer Philip Wylie was an eclectic novelist of some distinction, and he knew well enough to leave alone the celebrated “Are we not men?” sequence, in which Moreau paradoxically orders his subjects to assert their humanity (through vegetarianism and the forbidding of violence) or face inhumane torture in the House of Pain. The journeyman Kenton was a prolific director of over 130 films ranging from W.C. Fields and Abbott & Costello comedies to Frankenstein pictures. His work here is uniquely inspired, aided by Paramount Pictures talent like makeup artist Wally Westmore and cinematographer Karl Struss, both fresh from the previous year’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Much of the horror is implied—movement behind rustling shrubs, lurking figures scurrying out of dark caves, distant agonized moaning—but when the malformed creatures are glimpsed, they’re no less believable, frightening, and, because of their cruel, brainwashed captivity, sympathetic.

Back in front of the camera, Bela Lugosi has a poignant, heavy presence in the crucial role of the prodigiously whiskered Sayer of the Law, the best-dressed and most articulate of Moreau’s “things”—like them he’s neither man nor beast, as the horde laments in startling closeup. When order finally breaks down, though, he’s among the first to reach for the surgical scissor-assisted gruesome revenge. With his thickset, Lou Gehrig build, Arlen is a sturdy straight man, while Burke, star of the dime novel-esque movie posters and winner of a dubious Paramount casting contest/publicity stunt, is bewitching as the black-haired, ferally sexual foil to Parker’s prim blonde fiancée (Leila Hyams), though the latter is the one who gets the pre-Code pantyhose-peeling moment.

Even taking into account its pre-Code loose leash, it’s remarkable how much more daring, lurid, and intelligent this version is compared to newer models. Don Taylor’s bland, flatly lit 1977 version looks and feels like a movie-of-the-week, ideally half-glimpsed over a salisbury steak family dinner. John Frankenheimer’s 1996 folly isn’t without charms, very much including gonzo Brando but also Nelson de la Rosa as Majai, a mute mini-Moreau, and some inspired Stan Winston makeup, but its general disastrousness culminates in a laughably on-the-nose ending in which the narrator intones, “I look around at my fellow men and I am reminded of some likeness of the beast-people, and I feel as though the animal is surging up in them,” over footage of Rodney King and the like. Foregoing such overwrought spectacle and forced relevance, Island of Lost Souls is able to conjure infinitely more wit and horror with just the devious glint in Laughton’s eye. —JS

Sixth Night:

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

What would people make of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre if it had been given a different title? Something perhaps more discreetly ominous like The Last House on the Left, or simply evocative like Halloween, or abstractly expressive like The Shining. And furthermore, what would director Tobe Hooper’s career have been like? It’s the film—and title—that both made and marked his career; even those of us who believe it’s a masterpiece have to admit that it traffics in the kind of degradation on which a “respectable” career is not based—regardless of the often remarked-upon fact that it’s not as explicit as it’s cracked up to be. The actual onscreen gore may not have a patch on earlier splatter exploitation flicks by Herschell Gordon Lewis or later slashers in the Friday the 13th (open) vein, but the effect the film has on the viewer is exponentially greater, a testament to the power of effective camerawork, sound design, performance, and editing—the elements of cinema, in other words. Hooper, who died in August of this year at age 74, is rarely spoken of in quite the same breath as other auteurs like Romero, Carpenter, or Craven, but Texas Chainsaw is at least as great—meaning as skillfully terrifying—as the best films by any of those other directors, and it’s infinitely more merciless. And, of course, the title is perfect for such a big, pummeling lug of a movie.

Even if Hooper hadn’t proven himself repeatedly in the coming years as a horror director of rare commitment and versatility, 1974’s Texas Chainsaw would be enough to put him in the pantheon. For those who still haven’t seen it—likely because of the brute implications of that title—it’s both as repulsive as the title suggests and somehow transcendent of the cheapness it implies. This kind of nerve shredding can only be accomplished through a tremendous amount of care, and that Hooper was able to fold layers of dark humor into the film while never once short-circuiting its full-throttle suspense is further testament to a singular talent. In his hands, the tragic tale of five heedless young urbanites—Sally, her paraplegic brother Franklin, and friends Jerry, Kirk, and Pam—who stumble upon the lair of an inbred clan of cannibal craftsmen (they use the leftover bones like macramé) is more than merely grotesque: it’s a grotty, absurd parody of the patriarchal American family. Its various implements, including meat hooks, switchblades, sledgehammers, and of course, the titular buzzing device, are its deviant family’s tools of the trade, used as dispassionately and matter-of-factly as suburban mom might microwave a TV dinner or dad might push a lawnmower. In a master stroke, it’s implied but never shown that the kids will end up sold as BBQ at the local food stand: Leatherface and his simpleton brother, their father, and their desiccated, barely sentient grandpa are casual entrepreneurs, and hippie just happens to be on the menu this week—as it would be in next year’s Jaws. In both cases, it’s nothing personal.

Texas Chainsaw has to be absurd, because there’s no other way to reckon with its unthinkable insanity. Where other seminal American slashers are situated within a psychological framework, diagnosable (Psycho) or not (Halloween); or resolved via traditional revenge trajectories (Last House, The Hills Have Eyes), Hooper’s film is all the scarier for refusing to give its viewers a way out. Sally, the ultimate final girl, may get away, but do we? The nightmare goes on; Leatherface is still there on the side of the road, swinging his heavy, motorized sword like an overweight, drunken samurai. One might almost pity him if not for his nasty habits. Among the film’s possible titles, Hooper said, was Leatherface, which would have been an almost sweet tribute to its central monster.

Hooper’s status as auteur was probably irrevocably damaged by the drummed-up controversies around 1982’s Poltergeist, which many believe producer-writer Steven Spielberg had too heavy a directorial hand in—including some who worked on the production and others who were nowhere near the set. One could spend a fruitless eternity trying to point out the elements of the film that seemed more Hooper or more Spielberg (much as many critics pointlessly did years later with Spielberg’s posthumous Kubrick collaboration A.I.). Instead, appreciate the subtle domestic satire of Poltergeist and how perfectly it melds with its more blockbuster sentimentality. And then also notice the exquisite Gothic detail and spatial integrity Hooper brought to his you-can’t-do-that-on-television 1979 miniseries Salem’s Lot; the surprising formal elegance of the otherwise disreputable carny thriller The Funhouse; the genuinely unsettling childhood fears that palpate the edges of the otherwise camp Invaders from Mars. As all these films prove, Hooper knew horror was a balancing act, a place to go when nothing makes sense anymore. And you’re not necessarily looking for answers. —MK

Seventh Night:

Martin

In George A. Romero’s second film, the sort-of romantic, somewhat comedic counterculture picture There’s Always Vanilla, his shaggy drifter hero Chris has a reckoning with his father in the wake of the dissolution of his latest amour fou. The paternal life advice on offer to the wayward son matches the film’s title, and few truer words have been spoken in an American motion picture about the perils of everyday existence. They land because they come from an independently produced film made by a striver and dreamer who’d hit a grand slam his first time at bat, and was now consciously attempting to expand his reach. Romero struck gold with Night of the Living Dead, and wanted to prove he could do more as a filmmaker, but would consistently be pushed by the forces of taste and industry (and his own skillsets, to be fair) back into the same well he drew from at his career’s outset. There’s always vanilla. It’s terrifying and true, and especially melancholy in the context of Romero’s career.

What is scarier than real life, more frightening and daunting than the pressures of finding one’s place and charting a path through the world? Certainly not vampires, zombies, ghosts, or other things that go bump in the night. At least that’s something like the hypothesis of the sadly departed Romero’s highest achievement, Martin. In the film’s very first sequence, we watch the eponymous bloodsucker (John Amplas) in action. He’s boarded an overnight train from middle America headed to the coast and is in clear need of a fix. However, instead of overpowering his victim with preternatural strength and drawing her blood with fangs, he awkwardly corners the woman in her sleeper car, forcibly injects her with a sleeping drug, weakly pleads with her not to shout until she loses consciousness, strips her naked, and then slits her wrist with a razor to make his act look like an attempted suicide. Once he’s drunk his fill, he methodically cleans himself and the cabin and exits.

Martin certainly has the anemic look of a vampire—willow-thin, pale, aristocratic cheekbones, floppy dreamboat hair. He’s also barely verbal, avoids eye contact, and hunches when he walks. Perhaps what bends him over is the psychic weight of a family that’s insisted on bringing the Old World to the New, and whose scion, his elderly cousin Cuda (Lincoln Maazel), has determined via some alchemy that Martin is the latest cursed member of the family to exist as the Nosferatu of legend. Cuda picks Martin up from the train station in Braddock, PA, and brings him to a home filled with garlic and crosses, promising to save his soul, and threatening to drive a stake through his heart if he goes astray. Yet, even as we watch Martin continue his killing spree in his new hometown, Romero refuses us the answer to the most obvious question: is Martin actually a vampire?

In Romero’s rendering of Martin’s story, the boy’s potential vampirism does eventually become somewhat beside the point. And that’s a large part of what makes the film so special. Martin is more interested in the landscapes of decaying Braddock in the era of gas shortages, the lives of the people Martin comes into contact with as he works as a delivery boy in his Cuda’s grocery store, the relationship of Cuda’s daughter Christina (Christine Forrest, AD on Dawn of the Dead, and shortly to marry Romero) with her roughneck boyfriend Arthur (Tom Savini, Romero’s special effects guru). For her part, Christina knows she’ll dump Arthur sooner or later, but when he offers to take her out of Braddock, she jumps at this, her only chance. Meanwhile, as the days drag on, Martin loses himself in black-and-white fantasies in which he sports a cape and the bodices on offer are just pleading to be ripped. Perhaps his issue is less lust for blood than something else?

Visionary dreamers like Martin abound in Romero’s films—There’s Always Vanilla, Season of the Witch, Knightriders, Creepshow, Monkey Shines, Bruiser; they’re near as plentiful as the zombies he’s most recognized for. Martin’s visions not only suggest his mental disturbance, but also send up the kind of movie Martin was likely expected to be. Martin plots to murder a dissatisfied housewife, only to catch her in bed committing adultery. He considers a similar mark, Mrs. Santini (Elyane Nadeau), only to find himself on the receiving end of her sexual interest. As the film climaxes, Martin seems ready to throw off his dual yokes—he’s confronted Cuda’s superstitions and is settling into his role as a paramour to the local Mrs. Robinson. He seems almost lighthearted for the first time. And then, after Mrs. Santini is found dead by her own hand, Cuda kills him with a stake and buries him in the backyard.

Isn’t that always the way in this America of ours? You struggle through confusion, emerge into the light for one brief moment, only to have your dreams snuffed out. There are few filmmakers we’ve produced that have had a more clear-eyed vantage point on the twinned pitfalls and promises of the American Dream. And even in his most ham-handed of social critiques, he never lets his viewers elevate themselves above his material. (In many cases, we did just pay good money to see a zombie movie.) If Romero allowed the safety of distance, I’d daresay Knightriders would be in the canon, and Martin would be among our most famous of genre films. Martin isn’t “scary” in the conventional sense, yet it is always thoroughly discomfiting. This is intimately tethered to the film’s grounding in a depressed Rust Belt existence, its grubby aesthetic, its end-to-end ambiguity, and our deep identification with a sexually confused serial killer. There is always vanilla at the movies. Thankfully for a spell we were lucky enough to get George A. Romero. —JR