Be Kind Rewind

By Leo Goldsmith

Trash Humpers

Dir. Harmony Korine, U.S., Drag City

If ever there were a movie that cried out to be either accepted on its own terms or fucking hated, that film is Trash Humpers. This should come as no surprise as it is a film by Harmony Korine, a filmmaker whose very name incites temper tantrums or seething faux-indifference from cinephiles of all stripes. Each of Korine's films is (calculatedly or inadvertently) a provocation, and nearly all of them succeed in this regard. His never-to-be-finished auto-portrait Fight Harm, in which the director literally goads people into beating him up, would perhaps be the least subtle example of this career-long goal. But following in a close second place is Trash Humpers, which, in its very title, begs for immediate dismissal.

So, if you're not interested, or if you, like many, insist on taking some kind of personal offense to Korine's films, spare yourself the anguish. For those who imagined the comparatively normal, humanistic, even kinda pretty Mister Lonely was some indication of a career 180 for the director, I'm sorry to disappoint you. Trash Humpers finds Korine back in the grim and grimy universe of Gummo, a place of grotesquerie, bestiality, apathy, decay—and snickering, unrepentant jollity.

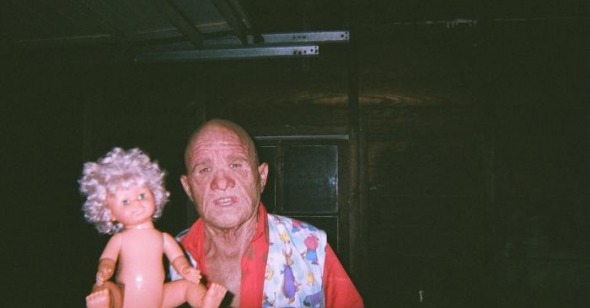

For the latecomers and those who haven't yet run screaming, a synopsis: A gang of elderly degenerates wanders aimlessly through suburban neighborhoods, wreaks havoc, and films their exploits on a decrepit VHS camcorder. All we see for the film's 80 minutes are the images captured on this device: The trash humpers squatting to crap on driveways and doorsteps; the trash humpers smashing televisions, cinder blocks, and boom boxes in a desolate parking lot; the trash humpers hosing down their wheelchair in a carwash at night; the trash humpers jumping on a trampoline in the middle of the street; the trash humpers partying with some fat prostitutes; the trash humpers ogling a garbage can, while offscreen other trash humpers grunt lustily, cackle maniacally, and chant, sing, or simply yelp, “Git it!”

If all of this sounds completely idiotic, it is. But Korine's perverse commitment to this idiocy holds the film together, allowing you to lose yourself (if you're so inclined) in its grisly and analog-fuzzy view of the world. Veering from the sublime to the repugnant, Korine maintains the form of a "pseudo-artifact" to the letter, plotlessly persisting with random interjections, long, pointless passages, maddening repetitions, and overall sloppiness. The film maintains a form of curious, mind-bending verisimilitude, and this is in no small way thanks to the masks worn by the cast (which includes Korine himself). The mask of the female humper (played by Korine's wife, Rachel) is perhaps a little too ghoulish, but those of her male counterparts more deftly, abstractly toe the line of the believable. With their clenched mouths, gnashing dentures, veiny necks, shrunken eyes, and odd age-discoloration, they're expressive enough that they consistently mess with your suspension of disbelief. Your brain tries desperately to make sense of these figures as something human, plausible, reasonable. Naturally, your brain fails, and this inability to reconcile what you're watching with any fully comprehensible provenance is what makes the film fascinating, even as it tests your patience or your gag reflex.

What Korine seems to be attempting here is a project similar to those of his sometime musical collaborators, the Sun City Girls (who provided half the soundtrack to Mister Lonely), who in their "Carnival Folklore Resurrection" series from the early 00s tried to recreate, imitate, and even mock various forms of world music and pass the results off as artifactual. (They’ve also long been fond of obscure cassette-tape releases well into the CD and MP3 ages.) However dim-witted this seems, neither the film nor the Sun City Girls' projects is as easy to pull off as it might sound, either technically or in terms of believability. In other words, contriving sloppiness and chaos and making it credible is no mean feat, with or without the use of abject, bargain-basement technology. Nonetheless, Korine very nearly manages to author his very own suburban legend of wild, geriatric savages who perform their bizarre, ritualistic evil seemingly for the pleasure of it, like bored, stoned teenagers: giggling, breaking shit, playing basketball, setting off bottle-rockets, inflicting violence on objects and people for no reason.

Of course, while all this sounds like gleeful stupid fun, there are also many nods to some of the more folkloric evils of the American hinterlands: peeping toms, dirty old men, wicked old ladies secreting razor blades inside apples, and, of course, racist hillbillies. A mounting undercurrent of terror drives this seemingly unstructured film forward with increasingly upsetting imagery, as the camera happens upon a row of blood-spattered white Velcro sneakers, or a naked corpse lying in the weeds. Through the miasma of VHS, Korine fashions an unsettling atmosphere out of the sound of porch- and street-lights buzzing, the sight of syrupy brown sunsets over highways and parking lots, and hot orange crisscross flares on the lens. The sight of Korine's own character wearing a confederate flag t-shirt while grinding his crotch against a tree is a particularly unsubtle piece of audience baiting, but there are weirder, more subterranean gestures, too. The soundtrack is largely devoid of music except for two songs that the humpers repeat (and repeat and repeat), both drawn from Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music: “Single Girl, Married Girl” (as popularized by the Carter Family) and a butchered version of “The Devil and the Farmer's Wife.” References like these, buried in the muck of bland contemporary Americana, suggest a sort of collective, subconscious evil that is uniquely rooted in the hollers and crevices of Appalachia. This is, in many ways, the film that Rob Zombie has been almost-making for years.

There are similarities here not only to weird, underground video ephemera but also to skateboarding videos of the Nineties (where Jackass gleaned most of its talent), and these suggest that the film's primary influences lie completely outside the realms of tasteful, beard-stroking cinema that dare not speak Korine's name. But the ultimate paradox of Trash Humpers is that it is a real movie—transferred to celluloid and everything. Sure, fetishists of dead technologies will relish the coy VCR-dubbing discursions, the lovely crisscross tracking issues, and visible "REW" and "PLAY" displays in the upper left-hand corner, but Trash Humpers is a film designed not for the personal use of a fictional video underground (like a snuff film, also something of an urban legend) but for the communal experience of a movie theater. In the cinema the experience is downright magical, what with the haze of video washing across the celluloid and people walking out after ten minutes and audibly cursing the film. (Somehow, the idea of watching Trash Humpers in your home theater is too depressing a notion to contemplate.) In fact, provocateur though he is, Korine is neither thumbing his nose at cinephilia, nor daringly embracing video, but rather paying curious tribute to both by resuscitating a format that’s even deader than film itself.