Charlatans

By Nick Pinkerton

Mister Lonely

Dir. Harmony Korine, U.S., IFC Films

Harmony Korine has returned, and the people whose solemn weekly duty it is to fill magazine column space could not be happier.

This tidbit opened a recent New York magazine profile: “It’s hard to imagine this today, but Harmony Korine was once considered a threat to something besides himself.” Not really—unless playing Groucho to Janet Maslin’s Margaret Dumont at the Times passes for subversive (the article also contains this nostalgic chestnut from Professional Art Personality Ryan McGinley: “Being bad with Harm back then was like shooting dope with Burroughs”—the mind boggles).

Harmony Korine’s masterpiece, to date, has been the creation and maintenance of his own niche celebrity brand, which depends on that bogus “threat.” He entered public life with Larry Clark’s Kids (1995), springing full-formed from a publicist’s wet dreams: “22-Year-Old Skate Rat-cum-Screenwriter Tells Tough Truth About Youth of Today!” It was a hook that had worked before (Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour tristesse) and which has been resorted to since (Nikki Reed’s Thirteen). The public persona he developed is inextricable from his films—it’s difficult to know what’s promoting what—and I’ll not attempt the separation.

Korine knew how to be famous right off; YouTubing his goof-off Letterman appearances, one has the impression that he’s an old hat, as inured and comfortable in his shtick as, say, Bobcat Goldthwait. He made friends fast. The belt-holding enfant terrible of the day courted Euro art-house stalwarts of the “adventurous era,” Werner Herzog and Bernando Bertolucci; apparently impressed and all too happy to be receiving attention from a younger demographic, they returned the tribute. Zelig-like, he’d go on to emerge in the company of Johnny Depp, Three 6 Mafia, Leo DiCaprio, David Blaine, Will Oldham, Mac Culkin . . .

Harmony, whose new film Mister Lonely is about celebrity impersonators, closely studied the second half of Herzog’s career, when the German director’s considerable talents were eclipsed by the self-mythologizing center-staging of his own folk heroic persona (Narcissus-like, Herzog seems to have fallen in love with his own image seeing the rushes of Burden of Dreams), and mystery gave way to Werner Herzog’s Believe it Or Not. As with Herzog, whose much self-referenced “madness” and deliberate naiveté always came with an element of Hamletian calculation, it’s always been difficult to extrapolate just how much what Korine said was so much class clowning.

The matter was further clouded by his art: 1997’s Gummo was a polarizing flashpoint with unforgettable slivers—taken on its own merits, though, it doesn’t weather comparison to the work being done in the same discomfiting documentary-fiction borderland by the still underappreciated Ulrich Seidl (1995’s Animal Love). After his debutante debut, Korine’s work seemed an increasingly secondary concern. There was a put-on opening at celebrity sponsor agnes b.’s Santa Monica gallery, full of Norse black metal allusions and race-baiting (celebrity retro avant-gardists like Korine, Vince Gallo, and Crispin Glover can’t seem to get enough tedious art-as-pseudo-ironic-hatemongering, the “subversive” flipside to Hollywood’s p.c. fatuity). A second film, julien donkey-boy, was, if memory serves, completely without merit—by some accounts due to a host of bad habits increasingly gripping the young auteur. And then, unlike Abel Ferrara who, if self-perpetuated legend is to be believed, blazes two jumbo crack rocks every morning over breakfast without missing a call time, Korine’s productivity dropped off, along with his teeth.

*****

In his motor-mouth heyday, Korine’s scope of reference was undeniable, even if that width came at sacrifice of depth. Nothing could pass through this great trivializer without being shrunken, anecdoted, and turned into tossed-off quirk or allusion in a contextual vacuum. Something like an art-house Dennis Miller, he transformed pop history into bric-a-brac, giving everything the value of the thrift store–bin “finds” that clothe the population of Gummo’s Middletown, Ohio. His 1998 non sequitur “novel,” A Crackup at the Race Riots—I’ve only read it in glanced excerpts, something I suspect the author would approve of, as it seems to have taken about as long to write as it does to read—is the quintessence of this tendency, a Tourettes’ rush of name checks. Its author’s stated enthusiasms are endless: Georgie Jessel. Linda Manz. Red Buttons. M.C. Hammer. Jean Eustache. Patrick Swayze. Manny “Pacman” Pacquiao (about whom Korine once wrote rather poetically). Leo Gorcey. Jessica Tandy. Varg Vikernes. Henny Youngman.

Celebrity obscurities aren’t Korine’s only mania: “For some reason I've just always been drawn to a specific kind of person: handicapped,” Korine has said, and an old friend remembers: “Harmony was of the belief that the freaks of nature in this world are actually God's special people.” Of course, such reverence is essentially inextricable from condescension—a tongue-in-cheek “tribute” to “midgets” on Mr. Show got at the sentiment: “Better than people/ Because you’re so slight/ We’re not so great/ Because we’re of normal height/ We wish we were like you…” etc. But the old “Is it empathy or is it exploitation?” argument is, finally, an eye-of-the-beholder dead end, so let’s just leave Armond White to the dutiful condemnation of Korine’s “fetishizing outlawry, kookiness, the insanely ridiculous and the Not-As-Smart-As-Me Other.”

Mister Lonely simply adds Performers, a doomed and beautiful breed here, to Korine’s list of “God’s special people.” In the broadest sense, Harmony just seems to voraciously love the famous (or would-be famous) in the same arms-wide-open way he loves anyone who can command attention: as with the handicapped, nobody can fully ignore a celeb walking down the street. I take Mister Lonely to be an attempted inquiry into that love and its implications.

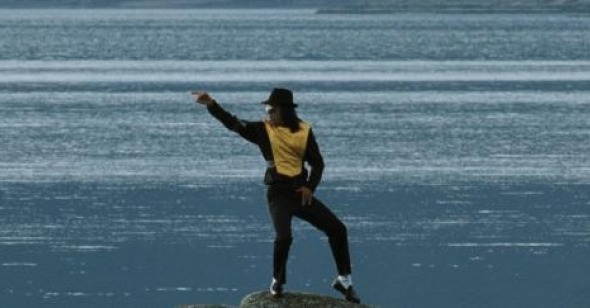

A Mexican Michael Jackson impersonator (Diego Luna) adrift in Paris works the Jardin du Luxembourg for change, returning home to an empty room. Like the isolated pop artist in Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer, he expresses himself and keeps himself company by tape recording his thoughts, presumably the voice-overs we hear throughout the film. Hired out to an old folks home, he meets a Marilyn Monroe (Samantha Morton) who invites him to join a commune for “people like us”—other impersonators—in the Scottish highlands. Disembarking there, he meets her husband, a covetous, sexually cruel Charlie Chaplin (Denis Lavant), as well as Sammy Davis, Jr., the Pope, Queen Elizabeth, a potty-mouthed Abraham Lincoln, James Dean, the Three Stooges, Little Red Riding Hood, and Buckwheat.

Hereon the story is a chain of episodic happenings, leading off toward the opening night of the group’s ramshackle handmade theater (I suppose it’s a joke that it’s built adjacent to the vast castle they inhabit). Performers rehearse atop the turrets, backgrounded by a shimmery loch. There are figures-in-a-landscape idylls. Marilyn flirts with Michael, and Charlot channels his jealous rage through ping-pong and assaultive fucking. The Pope has to be force-bathed before the show, like Warren Oates in Ride the High Country. Honest Abe spins a Harlem Globetrotters regulation ball on his finger and recites the Gettysburg Address over a crunk backbeat.

This said, Mister Lonely is Korine’s most sober, tripod-bound, articulate, concentrated, and professional-looking film to date—and, in many respects, his dullest. What attempts there are to recapture the old puckish spirit and the experiment of “people being displayed for their intrinsic qualities” (Jonathan Rosenbaum’s phrasing) is in that trip to the senior citizen’s home, where the grotesque humor seems forced (“Let’s never die!” shrieks Michael, before encouraging a chorus of “Woo-hoo”s). Seemingly surreptitious shots of the impersonators blowing into town to advertise their show are just cutesy hidden-camera pranks.

Nothing here approaches the delicate balance of infatuation and horror involved in, say, Drew Friedman’s portraits of drooping borscht belt veterans, but there is something of the gross, bathetic poignancy of a Red Skelton sad clown in the film’s autobiographical aspect. Part of the essential appeal of Korine has been his arrested-development acting out, a druggy Peter Pan performance lived beyond the boundaries of shame. He has been luckier than some: in the decade-plus since its release, Kids cast members Justin Pierce and Harold Hunter have died (aged 25 and 31, respectively), as has Rusty “Ol’ Dirty Bastard” Jones, whose tall tale life of outlaw Rabelasian schizophrenia was for some time a hotly followed wish-fulfillment serial. It would take a tremendous amount of bad faith in Korine’s motives (which some of his detractors—I’ve counted myself among them—do have) to imagine this hasn’t affected him.

A humble and hugely moving Iris DeMent album-closer (“My life—it don’t count for nothing”) accompanies the film’s mawkish emotional crescendo, piggybacking the movie toward mostly unearned transcendence. (The soundtrack is, in fact, one of the more beautifully curated in memory, including John Jacob Niles’s harrowing “The Maid Freed from the Gallows” in full, and Bobby Vinton’s title track.)

That straining for epiphany is ever present: Running parallel to the impersonators storyline is an unconnected subplot in which a gang of Panamanian nuns, led by Herr Herzog in priest garb, accidentally learn the miracle of flight-through-faith. Contrasting to the primary narrative, it offers a tragicomic ending to undercut the main story’s seeming turn toward growth/redemption—or maybe it’s just wedged-in as an experiment in juxtaposition (still, I can’t imagine anyone mourning the loss of this half hour).

*****

Korine’s influence on American film culture has been minimal, all told. I’m surprised to find myself thinking that this might not be entirely a good thing; slogging through any given season’s slate of “smart” indies, his spazziness seems a boon. His role in the broader context of “hip” culture as a whole is another matter. It would be ridiculous to accredit Korine as being a catalyst for anything—remember that he was follower enough to actually make a Dogme 95 film—but he has sometimes epitomized a certain tendency among my peers in quasi-bohemia (I’m 27) toward an uncritical worship of “creativity” marked by coy savantism, Neverland whimsy, and groupthink Kindergarten reinforcement (see: Weird Beard Freak Folk, Lukas Moodysson, galleries full of faux-primitive Magic Marker art) that is obfuscating and entirely indefensible.

And so, Mister Lonely: Occasionally indelible, full of childlike feeling—MJ’s bidding his Parisian studio goodbye nods to Margaret Wise Brown’s classic Goodnight Moon—speaking the virtues of growing up while wallowing in sorrow like an infant squelching in its diaper.