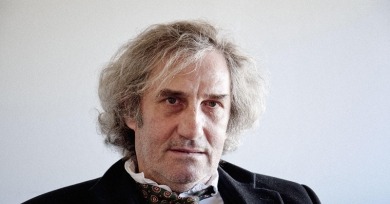

Vadim Rizov

The Paramount is the first theater I formed an attachment to for a reason other than it being a nearby multiplex. I have inevitable nostalgia for a space I haven’t entered in a decade: I don’t need to see it in person again to realize the lobby was even smaller than I probably registered.

Meyerowitz splits the tonal difference between his kinder Greta Gerwig collaborations (Frances Ha, Mistress America) and the more acerbic works surrounding those, dealing with the previously unlikely possibility of forgiveness and healing.

With its sentimental score, passage of seasons, understatedly treated deaths, and aversion to the kind of confrontation that would make viewers truly uncomfortable, this is very much a Kore-eda film, but there is a steely center.

When the camera slowly floats through communal areas, its relentless advance suggests menace; in close-ups the priests are pinned down with such entomological remorselessness that they nearly squirm.

I have no theory on my own film. You know, cinema is gestural; this is what it has in common with dance or with painting. You take your camera, and people, and you write something with that, that resembles life.

Rather than finding Russell idling around the same aesthetic cul-de-sac again, Joy is (mostly) a surprisingly straightforward, three-act rise-fall-rise drama that, after an enjoyably all-over-the-place start, becomes increasingly streamlined and focused.

Even if the film builds to a shrug, Baumbach is working at an increasingly sophisticated craft and dialogue level from moment to moment. Endless amounts of near-uniformly quotable dialogue come out at a clip only a shorthand writer could keep pace with.