Greatest Collaboration: No Other Land

When a film is described as “important,” it can overshadow the craft, as if to suggest its value is only educational. While Basel Adra and his collaborators Hamdan Ballal, Rachel Szor and Yuval Abraham intended to make a film that educates and contributes to Palestinian liberation far beyond the current ceasefire, No Other Land is also a work of art that responds intelligently and creatively to an ongoing, violent crisis. It is a miracle that this collaboration between Palestinian and Israeli filmmakers even exists, and that Adra was able to document the systematic destruction of his village of Masafer Yatta for five years, even as his faith in the power of images to move the West into action must surely have wavered in the face of the U.S. government’s refusal to stop funding “the first genocide in history where its victims are broadcasting their own destruction in real time.” The film's impact is not just a result of inherent pathos, but of the directors’ artistic choices, constructing a narrative that pushes forward while also flashing back to Basel’s childhood memories at key moments or utilizing home video and archival footage to show the village in the context of a wider fight for justice. It’s a meaningful choice to collaborate across identities in their apartheid state, and to show the strain of that collaboration as the brutality increases and only half of the filmmakers have the option of escaping to safety. The social relevance and importance of No Other Land doesn’t exist outside of its cinema—it is an integral part of it. Adra, Ballal, Szor, and Abraham’s grace and courage created a beautifully made film that is gutting, urgent, and yes, very, very, very, important. —Farihah Zaman

Biggest Leap of Faith: Union

The makers of Union, directed by Brett Story and Stephen Maing, called it in the air. Producers Samantha Curley and Mars Verrone had each been in contact with wrongly terminated Amazon warehouse worker Chris Smalls about a potential documentary project even before he spearheaded the most exciting development in recent labor history, the successful union drive at Staten Island’s Amazon JFK8 warehouse—a milestone for the underpaid, overworked, contingent modern workforce that keeps the Big Tech–dominated global supply chain churning. The film’s success—prime festival slots, critical acclaim—is apt reward for a commitment not so different from labor organizing itself, as the film depicts it: a long-haul slog, with no shortcuts or financial safety net, just the patience and belief to keep showing up for meeting after meeting, talking through tactics and harvesting footage. Union drives don’t always work, as the film also makes clear, and documentary subjects don’t always pan out.

As we enter a climate in which media barons such as Smalls’s old boss Jeff Bezos are preemptively bending to the new administration, Union is an implicit reminder of the importance of the loose network of progressive financiers, nonprofits and other grant-giving bodies that fund projects this uncertain and unremunerative. Distributors were so afraid of antagonizing one of post-theatrical Hollywood’s biggest players that the Union filmmakers ultimately self-released the film, which underlines the precariousness of politically, aesthetically risky nonfiction storytelling in a climate ruled by unshackled capital and dominated by access-driven celebrity brand-management exercises—and worse. Amazon just announced a $40 million commitment to a Melania Trump documentary series, to be directed by shrimp cocktail fan Brett Ratner and executive-produced by the First Lady herself. —Mark Asch

“I’m a Bitch, I’m a Mother, I’m a Dog” Award: Babygirl & Nightbitch

Bizarrely, two 2024 films wondered if a canine lifestyle could catalyze a mid-life feminist awakening. In Halina Reijn’s Babygirl, tech CEO Romy (Nicole Kidman) is wowed by new intern Samuel (Harris Dickinson), treat in hand, coaxing an unleashed dog back to harbor. She’s slack-jawed as he whispers “good girl”—god, she wishes that were her! The pair enter into a very vanilla BDSM relationship, a dynamic that could develop characters through specific fantasies and kinks, clear desires and boundaries. It’s like Samuel and that cookie: request, action, reward. But Romy rejects exploring any animalistic urges, too busy trying to define their wispy relationship status. At the end of the film, Romy, during sex with her husband (Antonio Banderas, far afield indeed from Pain and Glory), astral-projects to a dingy hotel room where she and Samuel had one of their first encounters. She envisions Samuel there, petting the dog: docile, stoic. Pay attention. She’s not the dog anymore—the dog now represents her desires being voiced, acknowledged, and accepted by her husband. (The umbrella term “desires” here applies to the truth of her affair and wanting to watch porn during sex.) Good girl! Is it weird that this “dog” is compartmentalized in a locked room in her mind? Don’t overthink it. Reijn already fumbled the metaphor much earlier by having Romy drink milk from a saucer, a rookie feline-coded error.

There’s a deeper, messier interest in parenting and aging in Marielle Heller’s Nightbitch, based on Rachel Yoder’s novel, but the metaphor is too literal. It’s in the realm of myth to watch Adams sprout a tail-nub and rip into a meatloaf with her incisors in public; actually seeing her dog-pelgänger pound the pavement in the second half takes us to a Homeward Bound sequel. The trope of the unnamed protagonist, now trendy, favors the archetypal instead of the specific—Mother makes anemically feminist art about her one-dimensional girlsquad, the animal within us all. But who, or what, is that dog in her?

Another 2024 work, Miranda July's novel All Fours, could teach these weary dogs a new trick. The book is also about a mother’s mid-life search for self and sensuality, and also prominently features a dog. Importantly, he's not a metaphor for experience, but a foil for human behavior. When July’s protagonist looks at her whimpering rescue dog, Smokey, she’s unable to model for him that “everything is fine” in her family home, per the vet’s instructions. She’s spent the book slowly, inelegantly groping forward to find herself, to escape labels like “wife,” “mother,” and “artist.” As she vents on the phone to a friend about how confused and horny she is, she imagines her dog asking her, Why? Why would a person behave with such desperation? The idea that she might so easily see and understand herself anew in that dog negates what it means not just to be human, but, crucially, to be her. —Chloe Lizotte

Go Big or Go Home: Samsara

Go Big: Lois Patiño’s reincarnation diptych Samsara simply needs to be seen in a theater, preferably on a large screen, with the sound pumped up. Not too much to ask, perhaps, for the latest overhyped horror movie or big-studio animated spectacle, but when the film in question is couched as “art film” esoterica and mostly screened in festival sidebars with titles like “Wavelengths,” it becomes trickier for most people to see it the way it was meant to be seen. I was lucky to take in Patiño’s overwhelming work during last year’s First Look festival in MoMI’s Redstone Theater, and it did get a brief theatrical run at Metrograph, yet Samsara has been otherwise unfortunately hard to witness correctly. While in outline and general feeling, one might recall Frammartino’s Le Quattro volte, the film’s journey is entirely its own beast. As it moves from Laos to Tanzania, the shift occasioned by the presumed rebirth of an elderly Buddhist woman into animal form, Patiño invites the viewers to close their eyes and drift into a visionless dream state, with an orchestra of sounds from within the “Bardo,” and slashes of light barely penetrating the eyelid. Don’t try this at home. —Michael Koresky

Go Home: I might be mistaken, but I believe Samsara received about five screenings during said theatrical run at Metrograph, leaving, with First Look factored in, the total number of times it has played in NYC to date countable on two hands with fingers to spare. I’d love to have experienced it first in a theater, but, alas, the link was to be my lot. (In the ever-increasing moments like these I hold close Kent Jones from our Reverse Shot Talkie waxing on about how he doesn’t care how a viewer encounters Touki Bouki, as long as they encounter it at all.) The “Bardo” sequence, especially, would seem to suggest the necessity of the theatrical viewing, but I had a queerly pleasing sensation while watching it: home alone, on my couch, my cat nearby, sun-slanting into a room overly bright for the sequence, comfy, with my eyes closed, lights flickering intermittently on my TV, sometimes barely perceptibly. Normally this might be the scene-setting for what we commonly call “a nap,” but somehow the familiar environs melded intriguingly with Patiño’s formal gambit. I was enraptured; it held my focus, left my mind cleansed for the drastic shift into the film’s second sequence. And I wonder if I would have been as receptive, as open a viewer, if I hadn’t watched it in my apartment, with my guard down. —Jeff Reichert

Most Convincing Aging: Fernanda Torres becoming Fernanda Montenegro in I’m Still Here

Least Convincing De-Aging: Richard Gere becoming Jacob Elordi in Oh, Canada

Best Supporting Actress: Michele Austin in Hard Truths

Marianne Jean-Baptiste’s slash-and-burn performance as aggressively unhappy Londoner Pansy has been rightfully and widely praised by any and all critics who took the time to watch Mike Leigh’s miraculous Hard Truths. Yet would Jean-Baptiste’s work be legible, and would Leigh’s film be bearable, without Michele Austin’s Chantelle? Pansy’s eminently patient sister, a single mom who runs a hairdressing salon, is the kind of character one might easily call “long-suffering” for all the fatigued nurturing she offers to her inconsolable sibling. Austin, however, never allows Chantelle to become a mere witness to pain, her fierce commitment to Pansy manifesting as neither masochism nor delusion. Leigh veteran Austin is brilliant at conveying how one often absorbs the narcissism of others: just recall her as Another Year’s new mother Tanya, hilariously ignored by Lesley Manville’s Mary at a backyard picnic amidst Mary’s whirlwind of egocentricity. Austin doesn’t communicate that Chantelle ever believes Pansy can be “fixed”—it’s unconditional love that provides the unspoken hope, even if she at times is at her own breaking point. At the film’s pitiless ending, we are given no indication that Pansy will be able to crawl out her self-entombment of shame, rage, and fear—what kind of a world is she expected to rejoin anyway? But if we turn our heads just a touch, realign our senses with Chantelle, whose comforting, give-and-receive relationship with her grown daughters (Sophia Brown and Ani Nelson) gives Hard Truths its warm counterpoint, then we might see Hard Truths for the optimistic film that it might just be. —MK

Best Supporting Actor: Adam Pearson in A Different Man

I’ll always remember my first experience watching Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin at the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival. Many people fled the screening during certain, unshakeable scenes, though I remember being in a kind of paralysis from both awe and strong identification, especially at the film’s turning point when Scarlett Johansson’s alien opts not to seduce a man to his death. Instead, she builds a curious, brief, but beautiful connection to somebody who, due to his facial appearance, has been cast out by society as a monstrosity. The man was played by a then nonprofessional actor named Adam Pearson. In Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man, Pearson plays actor Oswald, who embodies the very aspiration that former actor Edward (Sebastian Stan) had been chasing until frustration from being typecast and marginalized led him to an experimental medical procedure altering his face. While Stan has earned deserved plaudits for his lead performance, Pearson’s supportive role is subversive: Oswald is the one, not Edward, who gains stardom and fulfillment, and seems comfortable with who he is. A Different Man can at times feel unsparingly mean and acidic toward its targets—mostly actors, creatives, and the conditions of New York City living. But it does hit at resonating, if obvious, truths. Pearson’s performance allows the film’s caustic approach to go down more smoothly, blunting the film’s satirical edge all while delivering surprises to both the audience and Edward, best exemplified by the film’s undeniable highlight of Oswald crooning to Rose Royce’s R&B hit “I Wanna Get Next to You.” —Caden Mark Gardner

Most Tasteless Song(s): Emilia Pérez

Yes, we’ve all watched, jaws dropped, the clips of “La Vaginoplastia” on social media, shared it with friends as we awaited the inevitable response: “Is this really in the movie?” But may I offer up another candidate for the worst song in Emilia Pérez? The much less flashy “Papá” [aka “You Smell Like Daddy”] is squeaked out by Emilia’s cute little son as he remembers her pre-transition, recalling the vivid smells of his believed long-lost father while Emilia (Karla Sofía Gascón) tucks him into bed. And what does the tiny tyke remember daddy smelling like? Well, according to the film’s French compos(t)er Clément Ducol and lyricists Camille and Jacques Audiard, papa evokes the scent memory of many things: mountains, leather, car engine oil, Diet Coke with lemon, sweat, and food (“spicy, spicy”). The child keeps remembering, recalling the smell of “mezcal and guacamole.” There are some obvious questions raised by such lyrics: Does guacamole even have a memorable smell? Would a very small child even know the scent of mezcal? Do the filmmakers have other reference points for Mexico besides these clichés? “Papá” ends with Gascón tearful and clutching her hair at her son’s melancholy reminiscences. Audiard, who notoriously did not cast any native Mexican actors in his film about the Mexican drug cartels and casually boasted that he didn’t really do any research, seems to care little about the world he has created beyond its reflection of his own artistic ego. It’s perhaps received less attention than the other songs for not being set to tuneless, formless Europudding pop/hip-hop slop, but with its saccharine racism—and inherent idolatry of masculine touchstones—it’s perhaps even more tasteless. —MK

Best Sound Effect: Between the Temples

Over the last decade and a half, Nathan Silver has made microbudget films boiling over with curated chaos, tonal volatility, visible seams, and cringe humor, particularly in collective-psychotic set pieces that betray his roots as a onetime intern for the recently deceased experimental-theater godhead Richard Foreman. Witness the screaming-crying-throwing up breakdowns of a sober-living cult in 2015’s Stinking Heaven, the pregnant teenagers at a group home for unwed mothers dirty-dancing to Khia's “My Neck, My Back” in 2014’s Uncertain Terms. Between the Temples is comparatively smoothed-out, being a late-life coming-of-age story with a Sony Pictures Classics logo and cast featuring multiple Golden Globe nominees, but it still retains a Rothian scatological streak. Grieving cantor Ben (Jason Schwartzman) is a mess—he’s lost his wife, he’s lost his voice, his only friend is a geriatric B’nai Mitzvah who happens to be his former elementary school music teacher (Carol Kane)—and he’s moved back in with his two (2) Jewish mothers (Caroline Aaron and Dolly de Leon), living in their basement behind a door that keeps opening and closing at inopportune times, disrupting scenes with an anguished, quasi-human shriek.

According to Between the Temples’ editor John Magary, who designed the sound with supervising sound editor Arjun Sheth (the two were aided by re-recording mixer Ryan Price), the door creak is created from six free library sound files: three of various doors opening, closing and squeaking; one labeled “short-fart_01.wav”; one long file of a girl screaming, played backwards, and one shorter one, played forwards. The last-named, the freesound.org file “girl-screams-yes.wav,” was, Magary says, apparently extracted from the YouTube video “7.00!!! OMG!!! NEW PB! OMG!! OMG!!! SO CLOSE TO SIX!! OOMMGG!!!”, which—as many bat-eared Between the Temples fans have already theorized on Reddit and Letterboxd—was previously sampled by Skrillex on the song “Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites.” The sound pays off in the film’s climax, punctuating the expulsive crosstalk of a letting-it-all-hang-out dinner sequence as livewire and uninhibited as anything in Silver’s earlier work. Insistent and embarrassing, the earsplitting door sound effect is a reminder, like Ben's quest for spiritual and corporeal rejuvenation, of pure wounded, childish need. In Between the Temples, even inanimate objects have an irrepressible id. —MA

Saddest Streamer: Nutcrackers

In David Gordon Green’s pathetic feel-good Christmas comedy, Ben Stiller barely seems present as a single Chicago careerist who finds that he’s been left as the guardian of his dead sister’s four feral children in rural Ohio. But who could blame him? Green’s aesthetic of late is about as ugly as cinema gets, a cheerless succession of drab images that somehow seem even more visually repellent than those in his recent Halloween things. And while the tow-headed moppets playing the manic, potty-mouthed kid squad have a charming ramshackle quality—and seem indebted to the horrible white-trash tots in Garry Marshall’s toxic 1987 fish-out-of-water comedy Overboard—it’s difficult to believe that Stiller’s character would have a sister and brother-in-law who would raise their kids to be untamed beasts right out of some Benh Zeitlin nightmare. —MK

Happiest Cinematic Conversion: The Old Oak

Forced to inhabit a world that continually fails to learn its lessons, Ken Loach can’t seem to retire. Subtle decorum is best left to bourgeois filmmakers, while for all his personal gentility, Loach's stronger films have traditionally aligned with Jean-Paul Sartre (“I have dirty hands. Up to my elbows. I have dipped them in shit and in blood.”) But his latest, about a publican in a northern English mining town who connects with a young Syrian refugee to open a soup kitchen at the back of his pub, values sentimentality over anger, and fantasy over realism. Turning on the intransigence and fear of his traditional heroes (the impoverished patrons of The Old Oak, betrayed by the system, who reject the arrival of the Syrians in their village), Loach—who films one magnificent dialogue sequence in a church— introduces an almost catechistic alternative. So improbable is the film’s denouement that it takes on the status of a prayer, or at the very least a statement of faith in cinema’s ability to knock humanity off its ill-fated trajectory. —Julien Allen

Least Convincing Climax: The Brutalist

Let’s concede that any hefty film with grand, novelistic aspirations requires some kind of a slam-bang finish. And let’s even accept for a moment that the awful sexual assault that occurs amidst the imposing quarries of Caracca, Italy, is meant to actually be occurring in the realm of the characters’ reality and not merely as a thudding metaphor: Capitalism rapes Art. Even still, screenwriters Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold paint their script for The Brutalist into a bit of a corner with this left-field shocker, using it to advance the narrative to some form of closure. The film subsequently climaxes with Felicity Jones’s Erzsébet crashing a dinner party thrown by Guy Pearce’s mustache-twirling titan of industry Harrison Van Buren, hissing at the “evil rapist” who violated her husband in front of his guests and grown children including Harry (Joe Alwyn), who violently drags the disabled woman out of the dining room and across the floor. Van Buren vehemently denies the claim, yet summarily disappears from the house and from the film, presumably to kill himself, though the film declines to tell us for certain: we just see protagonist László’s cruciform sun-shape as the dawn rises on his unfinished building. It’s a strange bit of symbolic caginess, especially coming so swiftly on the heels of a scene so lumberingly literal and awkwardly staged, but it gets to the heart of the unresolved tension of The Brutalist, a film of earthy realism burdened by ethereal allegory. But then… —MK

Most Restorative Epilogue: The Brutalist

Just as Brady Corbet’s immigrant epic The Brutalist seems poised to collapse under the weight of the literal-minded metaphors of its second half, it swerves in an unexpected direction for a coda billed as an “epilogue.” Flashing decades past the power struggle between architect László Tóth (Adrien Brody) and his benefactor and sometimes-antagonist Harrison Van Buren (Guy Pearce), the film finds a wheelchair-bound, latex-aged Tóth in Venice, poised to receive a career achievement award at the Biennale. His middle-aged niece Zsófia (Ariane Labed) accepts the award on László’s behalf, as time and illness appear to have robbed him of his ability to speak. But his buildings are his legacy, his voice, and his intervention in history. Nestled in Zsófia’s accounting of László’s accomplishments is an exegesis of the community center in Doylestown, PA, that occupies the film’s narrative. Here we learn that the building, with its chapel and cruciform center—which casts the shadow of a cross on the altar below at midday—was in fact modeled on the concentration camps László and his wife were sent to during the war. It turns out that even if you slap a cross on a building, you can’t take the echoes of antisemitic genocide out of its architecture. And so, a movie that seemed ready to bow on the obvious point that capitalism rapes art recasts itself as something deeper and more sorrowful. Though László’s journey as an immigrant and as an architect striving to realize his vision propels the film’s story, the movie’s destination is spelled out with eloquence, as a voiceless László looks on: one couple’s personal experience of historical trauma has been memorialized, through art, for future generations to grapple with, contemplate, and, perhaps most importantly, to live with—history and memory made present and physical. —Chris Wisniewski

Most Gutting Last Line: I Saw the TV Glow (“I’m sorry.”)

Most Gutting Lack of a Last Line: Juror #2

Most Rocking: Deborah Stratman’s Last Things and Robert Zemeckis’s Here

It’s a delightful surprise that my two favorite American films of the year, though they were created and conceived at the farthest opposite ends of the industrial spectrum, were concerned with existing in geologic time. Stratman’s desktop essay Last Things, made in large part under quarantine, cheekily invites us to consider the world we inhabit from the perspective of the inanimate (or are they?) rocks around us. Her assemblage of largely static compositions interwoven with interviews, readings, and occasional music is lean in means, but, as we’ve come to expect from the filmmaker, it’s vast in impact. Even holding at her preferred 50-minute runtime, this may be her largest film. Meanwhile, techno-fascist wizard auteur Robert Zemeckis’s Here takes a similarly long view in adapting the experimental graphic novel of the same name. His new film deploys a fixed camera perspective and digitally fractures the frame: at times, we may see in the main portion of the image the film’s despairing core narrative—about the preordained failure of the Baby Boomers and how this blinkered subsequent generations, America, and the world—while a corner reveals a rock landed on that spot from a comet blast a gazillion years ago, stubbornly continuing to persevere though it may now be covered by this unhappy suburban home. Both filmmakers, through incredibly different aesthetics, invite us to think far beyond our brief human time on Earth. It’s the stuff of great art! [Programmers take note: I’m available to discourse on this excellent future double bill at length. Anytime, anywhere.] —JR

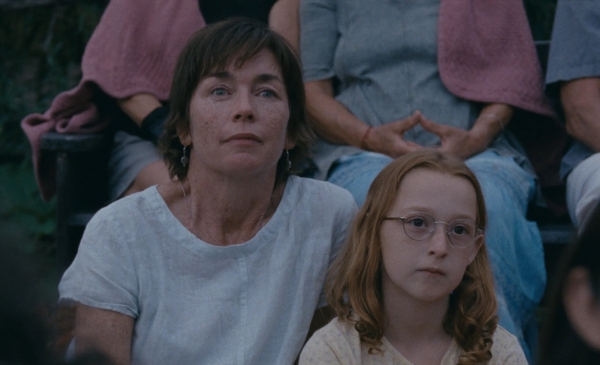

Most Compelling Center of the Universe: Julianne Nicholson in Janet Planet

Julianne Nicholson first appears as a tall, white-clad angel in Janet Planet, greeting Lacy (Zoe Ziegler), the child who has just upended her summer by demanding rescue from camp, with with a tender embrace. Is it any surprise that Lacy’s friends want to meet her? But this entrance is about as beatific as Nicholson’s characterization gets. As the object of filial obsession in Annie Baker’s debut, Nicholson’s title character, a Massachusetts-dwelling single parent and acupuncturist, is a mercilessly self-critical and perpetually error-prone figure whose feet are firmly planted in the ground sinking beneath her.

For decades now, Nicholson has been doing the type of modest, character-serving work that would have doomed her to underrated status were it not for her Emmy-winning turn as Kate Winslet’s wry bestie on Mare of Easttown (2021). That character, a fiercely protective Philadelphia mom, could probably unnerve the chronically indecisive Janet on cruise control, but Nicholson brings the same even-tempered soulfulness to both women; it’s easy to imagine her riveting us as the center of a seventies-era women’s picture like Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore or An Unmarried Woman. In Baker’s film, Nicholson embodies maternal overindulgence with a gentle, rueful knowingness. Every so often, she appears on the verge of rolling her eyes in protest at the latest odd request of her admittedly odd daughter. But that would require too much effort; it is easier, instead, to take a break and capitulate to the 11-year-old who still sleeps beside her. Of course, Janet is as dependent on her daughter’s approval and adoration as Lacy is on her mother’s, and Nicholson’s languid, hushed performance is attuned at all times to the toll it takes to constantly suppress one’s own miseries in order to shore up the touch-and-go happiness of a growing child. The delicacy of her voice and the slipperiness of her pauses are particular marvels, never more so than in a bedtime conversation between Janet and Lacy about the latter’s potential lesbianism, a heart-to-heart that pivots around Nicholson’s ability to convey both the wonder and worry with which mother regards daughter. This moment and this performance reside in the sigh taken before either laughing or weeping at the shambles of one’s life. —Matthew Eng

Most Compelling Satellite: Elias Koteas in Janet Planet

From the early 1990s to 2013, filmgoing connoisseurs of Elias Koteas, a Québécois actor of Greek descent, were eating very well indeed. The flinty, tender, but vaguely menacing and always compelling Koteas would routinely pop up in high and low fare in supporting roles, in between the occasional major performance (Exotica, Crash, The Thin Red Line, Two Lovers). Post-2013, he has only appeared in four films, devoting much of his talent to a suite of Dick Wolf TV dramas with “Chicago” in the title. So it was a gift last year when he materialized in Annie Baker’s Janet Planet, a wonderful film that belongs to the two female leads (a mother-daughter pair played by Julianne Nicholson and Zoe Ziegler), but on which Koteas, with limited screen time, bestows his special kind of spiritual mystery (or, again maybe, menace).

In the film, structured around the relationships of Nicholson’s Janet, Koteas’s Avi supplants Will Patton’s Wayne (who doesn’t surrender without a naked late-night scene in Janet’s front yard, which in a worse movie would have involved shouting) and sorta-friend Regina (Sophie Okonedo), who herself used to be under the spell of the charismatic Avi, a theater troupe leader. Janet knows that Avi manipulated and hurt Regina, but she cozies up to him anyway, a move that could be seen as cruel to both Regina and herself, one of several questionable—but genuine and human—decisions for which Baker refuses to vilify Janet. Avi needs to come across as alluring enough to attract these women, and simultaneously a little scary and a bit of a clown, and Koteas embodies these contradictions elegantly. At a dusk dinner with Janet and Lacy on Janet’s backyard raised patio, the bearded Avi bloviates (not uninterestingly) about God’s billions of years of inaction before deciding suddenly to create everything. He then says we all become God when we create, at which point you can see the cynicism subtly flash on Lacy’s face. Janet is sufficiently impressed, if only because Avi’s big talk is a vacation from her insular worries. Koteas also figures in the film’s mystifying, beautiful final scenes, which shouldn’t be spoiled, but his reading from Rilke’s “Elegy IV” at a bucolic hillside picnic, and the unexplainable enigma that follows, surely rate with 2024’s best cinematic moments. Let’s hope Koteas continues to vacation away from Dick Wolf’s Chicago. —Justin Stewart

Least-Seen Visionary Architecture: The Brutalist

Least-Visionary Visionary Architecture: Megalopolis

Most Insane Architecture: Heretic

Biggest Ball Drop: Late Night with the Devil

Cameron and Colin Cairnes’s 1970s-set horror takes place entirely in the studio of a late-night talk show on Halloween that gradually devolves into nightmarish mayhem with the interview appearance of an allegedly possessed girl and her caretaker. Terrific idea and not just for the retro production design and detail that can be achieved on a low budget—there’s something pleasurably unnerving about a film centered around a long-buried, unearthed broadcast, taped in the pre-VCR days, of an episode that would have had to live in the minds of TV viewers as an eerie “did I really see that?” memento. Unfortunately, after all its meticulously designed buildup, and just as the film reaches what might have been an eerie conclusion, it explodes into maximalism, featuring some very silly and very unscary special effects that look straight out of Ghostbusters, diluting the tension and undoing the entire demonic conceit. The insidious possibilities were endless; the film settles for forced, big-tent surreality. —MK

Holding Fast Award: Francis Ford Coppola, Megalopolis

In Finian’s Rainbow (1968), there’s a marvelous practical effect that, in some ways, traces the contours of Coppola’s filmmaking career: newly minted lovers Sharon McLonergan and Woody Mahoney croon to each other in Rainbow Valley, a small town in the imagined state of Missitucky. They’re clearly being filmed outdoors, and the feel is one of warm naturalism. Yet as the camera tracks to follow them, they pass behind a large tree, which becomes a wipe obscuring a cut that allows the pair to emerge into an incredibly synthetic, idealized forest scene, the kind of which we only see in movie musicals shot on soundstages. It’s gorgeous, in a completely different way than what we witnessed just a second prior. This kind of collision, of the real and the created, grandeur and silliness, a committed passion for things that only movies can really do…these are the elements that have come to define the cinema of Francis Ford Coppola if you look past his four most canonized films.

What do you do if your filmmaking career is defined by a handful of seminal works that, as they move further and further in the rearview, seem less than representative of the filmmaker you’d like to be? I guess if you’re Francis Ford Coppola, you sell part of your wine business so that you can conjure Megalopolis, perhaps your wooliest, most wondrous film. All the ways Megalopolis is preposterous have been noted ad nauseam. But to focus on this as a surprising turnabout suggests perhaps we haven’t really been watching Coppola films for the past four decades. It is precisely this preposterousness, the utter earnestness of its presentation . . . the cockeyed optimism and belief in a better path forward for humanity . . . the grandness of the endeavor, the commitment to each and every last little bit of it that marks it as maybe his most Coppola film yet. For those who’ve been charmed by late entries in his filmography, Megalopolis exists in a similar visual vein. The filmmaker is now 85, so we may not have him with us for much longer, but perhaps he might be willing to sell a bit more of the vineyard to grace us with one final offering? —JR

No Calzone for You: Nosferatu

John Cassavetes once said, “The greatest location in the world is the human face.” My chicken-scratch notes from a packed press screening of Nosferatu read, “We are hiding the face. This is embarrassing. Why?” From Jacques Tourneur to The Blair Witch Project, horror has thrived—fed—on the art of suggestion. In the moments before a monster emerges from the shadows, imaginations are in overdrive, possibilities are infinite. Robert Eggers, dutiful and surface-level as ever, keeps Count Orlok’s face hidden from view for much of the first act, but this obstruction is distractingly effortful. The camera peers at Thomas Hutter from over Orlok’s shoulder, the blurry silhouette of his withered skull occupying the left third of the screen; later, the camera glides into his office, keeping his face completely in the dark, repositioning such that we see an ominous silhouette. We hear him, though, in a booming basso profundo reminiscent of a Powerpuff Girls villain, punctuated by affected gasps for air. The buildup feels interminable, but the eventual payoff is chilling: a Nüsferatu mustache reveal.

This sort of silliness rang a bell: the compositions often mirrored the George Steinbrenner scenes in Seinfeld, anchored in a vocal performance from Larry David. A stand-in for the Yankees owner would always be framed over the back of his head or over his shoulder as he sat at his desk, yammering to hapless employee George Costanza. Both pairs of men have broken bread together, but whereas Orlok can only anticipate the possibility of blood spilled from a careless bread knife, Steinbrenner can effusively emote about the pleasures of a calzone: “The pita pocket prevents it from dripping. The pita pocket!” David’s rapid-fire speech and buffoonish register sell a ridiculous, oblivious earnestness in the character, a motormouth who didn’t need an audience. Seinfeld is full of stylized vocal deliveries—J. Peterman, Putty, Frank Costanza—that cement who each speaker is.

The name “Count Orlok” may conjure the faces of Schreck or Kinski, but in Eggers’s shadows, there dwells a face morph of Frank Zappa and Megamind. This Orlok lacks the loneliness—that sense of endless, hellish life lived—that made earlier versions of the character so precise and haunting: contrast Bill Skarsgård with Kinski, framed by Werner Herzog completely, plainly in the light, soft-spoken and melancholic, prone to genuinely off-putting shortness of breath. There’s nothing wrong with change, but there’s no sense of unearthly intrigue in Eggers’s vampire, which is strange for a movie that has Willem Dafoe assert he’s seen things that would make Isaac Newton and his laws of motion “crawl back into the womb.” Without that mystery, Orlok’s manipulation of Hutter to sign his real-estate contract, inscribed in a language the mortal cannot read, has stronger overtones of Nathan for You than genuine occult magick. Perhaps the greatest tragedy is that it is physically impossible for this undead party-rocker to praise the pita pocket. —CL

Most Poignant Appearance: Amber Benson in I Saw the TV Glow

Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s queer trailblazer Tara (Amber Benson) infamously suffered the indignity of a violent death, which, to add insult to injury, was destined to be repeated ad nauseam in weekly “previously on” recaps. How lovely to see Benson resurrected, if only for a brief moment, as a nurturing suburban mom in I Saw the TV Glow. Benson’s tiny cameo has a meaning beyond metatextual in-joke: the brevity of the moment is all the more touching for her being one of the few characters to show our doomed protagonist Owen any care or concern.—MK

Most Puzzling Appearance: Harris Dickinson in Blitz

Steve McQueen’s multicultural portrait of a beleaguered London during the height of World War II’s German bombing raids, Blitz had a rosy-cheeked Dickensian sweep that nicely, if weirdly, off-set its grim subject. McQueen’s landscape is dotted with classical character types surrounding the parallel journeys of Rita (Saoirse Ronan) and her young son George (Elliott Heffernan) to reunite amidst the destruction. But the recurring appearance of Harris Dickinson, as a soldier who keeps popping up on the sidelines of the main narrative, just confounds. A charismatic performer, Dickinson simply looks longingly at Rita, as though waiting for his narrative to kick in. Will it be a romance? A daring rescue? None of the above, which refreshingly goes against expectations, but mostly made me wonder if Dickinson was left mostly on the cutting room floor. Maybe he’s this WWII film’s Adrien Brody; alas, this ain’t The Thin Red Line. —MK

Not-So-Secret Weapon: Mikey Madison in Anora

At the end of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood (2019), Mikey Madison’s Manson girl got blowtorched to death. Yet what I most viscerally recall from that sequence is not the sadism but the actress’s decibel-shredding banshee wail. Madison had earlier secured my devotion as Pamela Adlon’s eldest daughter on the series Better Things: in an era of recessive, soft-spoken portrayals of female adolescence, her performance felt distinctive for the clamorous heights of its petulant discourtesy and undertow of easily wounded insecurity. It’s thus a delight to see Madison shine and reap plaudits as the gum-chomping, iron-nerved sex worker Ani in Sean Baker’s Anora. Praise has been heaped on Madison for her credibility in the role, from the dexterous twerking to the Brooklyn accent carefully honed by the born-and-bred Angeleno. But her work is brash, bold, and unbeholden to verisimilitude: stomping around the boardwalk in stilettos, elongating her vowels in a gleefully broad Brighton Beach squawk, and collapsing her face into the iciest of death stares. She puts me in mind of any number of effervescent comedic predecessors: Jennifer Jones wielding a wrench with a smirk as the improbable plumber Cluny Brown (1946); Shirley MacLaine’s Sweet Charity (1969) singing “If My Friends Could See Me Now” to the head of a tiger-skin rug; Madeline Kahn’s Trixie Delight grumbling “Aw, son of a bitch” while staggering on a hill in Paper Moon (1973); Marisa Tomei’s Mona Lisa Vito stomping her feet in rhythm to the ticking of her biological clock in My Cousin Vinny (1992). Like these actresses, Madison stirs up a fine frenzy while exuding an almost fantastical charisma. Like Simon Rex in Baker’s Red Rocket (2021), she unleashes an uncorked, dizzying energy that is as integral to the flow and feel of the film as any decision made by its director.

If Anora amounts to more than a joyride, it is because Madison preempts her character from being wholly subsumed into the exhilarating and exhausting chaos of which Ani is casualty and agent. Depth and interiority aren’t the achievements here but rather a truculent vitality that refuses to flatter Ani but also ensures that she will not incur slights and abuses quietly. Her final, lachrymose note of devastation may give Anora tragic heft—an admission of pain that emanates less from loss of love than being reduced to a disposable commodity. But, as in the Tarantino film, the fight lingers longer and more vividly in the memory than the defeat. What I ultimately cherish most in Madison’s performance is not a ring of truth so much as an impudent playfulness, the joy she evinces—and inspires—by acting out for a willing audience. —ME

Hardest to Watch (Content): Green Border

Hardest to Watch (Form): Emilia Pérez

Most Ghoulish Grin: Red Rooms

Forget Smile 2. When fashion model Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy) flashes a wide-eyed, big ol’ toothy grin in the final moments of French-Canadian filmmaker Pascal Plante’s chilling portrait of true-crime obsession, I experienced a full-body shudder. Taken from a distance, which is in keeping with the film’s unsettlingly ambivalent rendering of contemporary surveillance, the shot finds Kelly-Anne snapping a selfie while perched on the bed of a teenage girl who had been horrifically murdered in a snuff video viewable to the highest bidder on the dark web—and whose killer’s trial she has been strangely, unhealthily following with dead-eyed precision. It’s the dead of night, and she has broken into the house while the girl’s traumatized parents sleep in the next room. As always, Kelly-Anne’s motivations are murky—and there’s even the hint that what she’s doing in this moment will have a positive effect in the outcome of the trial. But her actions here—and that smile—are absolutely horrifying. Is the film a portrait of a particularly 21st-century sociopathy, bred of desensitization and narcissism, or have Kelly-Annes always existed, just in other shapes? Why does Kelly-Anne look at the evil things she looks at, and, by extension, why do we? It’s not enough to say that Red Rooms doesn’t “give us answers”—Plante knows that to even ask the questions is the beginning of a trip down a very dark rabbit hole. —MK

Best Newcomer: Lily Collias in Good One

The kind of intelligent, unforced low-budget American movie we used to get on the regular 25 to 30 years ago, but which now seems lost in the avalanche of overly stylized calling card features, India Donaldson’s Good One is anchored in the gravity of Lily Collias’s performance. As 17-year-old Sam, Collias remains open, curious, and good-naturedly skeptical for most of the film’s running time, bearing bemused witness to the competitive camaraderie between her divorced dad (James Le Gros) and his longtime buddy (Danny McCarthy) during a camping trip in upstate New York that was originally supposed to also include Matt’s teenage son. Despite a situation that would rightfully make any teenage girl batty with boredom and irritation, Sam makes the most of it, and Collias is mesmerizing in her character’s mundane peace-keeping mode. Yet something happens during the trip—something alarming and deeply upsetting that Donaldson allows to stay meaningfully subtle in terms of dramatics—that transforms Collias’s face into a topography of barely withheld emotion. She is hurt, disappointed, disgusted, confused, and finally resilient, and Collias expresses it all with supple inquisitiveness. Pair Good One with Annie Baker’s Janet Planet for a deeply moving double feature about seeing, really seeing, this painful world—and a parent—for the very first time. —MK

The Jaume Collet-Serra Award for Achievement in Films Directed by Jaume Collet-Serra: Carry-On

It’s back. He’s back. Reverse Shot stopped giving this award some years ago, after bestowing it upon Jaume Collet-Serra’s taut 2016 Blake Lively vs. Shark epic The Shallows. The pause was, at first, a contentious choice given that more than a few of us cast ballots for the director’s masterful 2018 paean to public rail transit, The Commuter, but a quorum could not be reached. Jungle Cruise (2021), his first, and hopefully not last boat picture, was an intermittent hoot, but even the die-hards among us were ultimately forced to admit the theme park ride adaptation was strictly kid stuff. We took a pass on calling a conclave around the release of his de rigueur Marvel entry Black Adam, even if this writer hopes to find it staring back at him from a tiny television in an airplane seat someday. Thankfully, 2024 brought us Carry-On, just under the wire. And for 119 glorious minutes, things seemed right with the world. Jaume’s back on his grind, working with his favorite tools: a B-movie narrative conundrum, a handful of actors bought in and punching above their weight, vehicular transportation, a ticking clock. Though the film stays grounded within an airport terminal for most of its length (and Ratchet and Clank habitué T.J. Fixman’s script makes merry hay with the stasis we encounter upon running headlong into airline security), our most ingenious contemporary director of action finds countless ways to hurtle his dramatis personae through this sandbox. One such sequence, a fistfight that takes place entirely within the bounds of a speeding, crashing, and then flipping police sedan, was thrillingly staged enough, even if digitally, to leave me, arms raised, cheering from my couch. —JR

The Barry Jenkins Award for Achievement in Films You Can’t Believe Were Directed by Barry Jenkins: Mufasa

I once cued up Chloé Zhao’s The Eternals on an international flight and had the oddest sensation: here, it seemed, was a movie subject that matched her abilities as a filmmaker. Unlike her discomfiting earlier blends of reality with narrative, The Eternals was wholly fit for purpose, and if I don’t remember a thing about it today, I can say for certain that I wasn’t bothered by it. I am thankful that I didn’t grok the same feeling from Barry Jenkins’s ungainly foray into Disneyland world building, Mufasa. This horrendous-looking prequel to The Lion King features all the visual beauty of an AI’s imaginings, and even if Jenkins is reported to have crafted some scenes around his beloved long, swooping takes (I chuckled at a trade article heaving to connect Mufasa to Béla Tarr), it’s hard to feel much of an artistic personality at work in a product so deeply committed to the delivery of fan service. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s songs are horrid (cue up “Bye Bye”—I dare you), the narrative herks and jerks, and the screenplay’s framing device sees what little energy the plot manages to muster blunted by regular cuts back to Pumbaa and the other one making pee-pee jokes. But none of that is important here—storytelling, character, artistry: phooey! All that matters is working up to an image of Mufasa roaring on Pride Rock. Am I being unfair for having hoped for a little more? Jenkins has politely suggested the world of big-budget CG just isn’t for him, and it’s good to hear it. Come play with us, Barry. Forever and ever. —JR

Most Skin-Crawling Scene: Last Summer

There’s a moment late in Catherine Breillat’s Last Summer that finally reveals we have not been watching a sensationalized drama about an inappropriate sexual affair but rather a ruthless examination of the corruption people will blithely engage in to maintain positions of power. Léa Drucker’s lawyer Anne—whose job entails guarding the young and vulnerable from abuse—has been cornered. Her husband Pierre (a crushing Olivier Rabourdin) has returned home from a weekend with Théo (Samuel Kircher), his troubled son from a previous marriage, with a shocking truth that we already know: Anne has been fucking the 17-year-old. The camera stays trained on Drucker. She’s a spider caught in her own web; her face falters. Is she about to crumble? Is she about to weep? Beg forgiveness? She slowly rises, her expression suddenly a mask of steely resolve, twisted by—shame? No, self-righteousness. Her eyes widen in horror. Confronted, she does not slacken. She strengthens, she gapes. The mere idea, the question, is so horrifying to her sensibilities—to human decency! Her husband is the monster, the sick one, for even suggesting such a thing. For believing the boy’s lies. The words of a mere child. Pierre breaks down, begs for forgiveness, the tables completely turned, paving the road for Last Summer’s jaw-dropping final act, a series of emotional and legal mind games to discredit Théo, leading to a mournful last scene that is in every way an improvement on the film’s source material, the frosty 2019 Danish drama Queen of Hearts. Even if Pierre knows the truth, as it is quietly indicated right before the credits roll, he will choose to continue to live in the murky yet safer zone of not admitting it. The collateral damage is only one young man’s life. —MK

Most Overexposed: The Guadagnino Twink Parade

Most Underexposed: Alvise Rigo in The Room Next Door

Least Welcome Subplot: The Cops Routine in Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point

Amidst the confectionary overload of Tyler Taormina’s hellzapoppin’ head trip through the psychotic nostalgia of Christmas in America, there’s one truly sour spot: Michael Cera (also a producer) and Gregg Turkington as lonely local cops Officer Gibson and Sergeant Brooks. Bored and lovelorn while patrolling the Long Island suburbs on Christmas Eve, ready to do their worst but even readier to let the local kids live and let live, Gibson and Brooks are not vivid characters so much as vessels for these comic actors’ deadpan personas, and their flatly oddball interactions, though meant to edge into the surreal, too often fall back on tee-hee gay jokes and tepid comic catatonia that come across like the result of wayward improv (I was mildly surprised the closing credits didn’t have one of those tiresome reels of joke outtakes). It’s understandable that Taormina would want to get the most out of the generosity of these performers, devoting their time to this distinctive, low-budget endeavor. I rarely doubted the film’s overall sincerity, although these scenes struck a false note, laying bare the film’s inherent blackout-sketch quality, and threatening to derail Taormina’s singular vision. —MK

Biggest Anticlimax: Saturday Night

Saturday Night, Jason Reitman’s heavily fictionalized rendition of the buildup to the 1975 premiere of Saturday Night Live (then without the “Live”), crowbars an unlikely surplus of incident into its four or five hours of plot time, but even still, due to the nature of its concept, it was bound to omit details and side characters precious to true SNL lore-nerds. The most conspicuous absence of all, though, is, oddly, funniness. Not really even a comedy, the film follows the chaos that ensues when the “not ready for primetime” troublemakers are given the keys to the NBC kingdom and throw together a live variety show with little time and less network support (the suits allegedly want Gabriel LaBelle’s Lorne Michaels to fail, if Cooper Hoffman’s Dick Ebersol is to be believed). Like Aaron Sorkin’s Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, the variety-show stakes are treated with the same life-or-death urgency as the nuclear threat in Fail-Safe (1964), which in fairness is how such a scenario would feel to those with comedy careers on the line. But you think there’d be an attempt to convey why all this heartrending stress mattered and was worth it, i.e., that it produced a high-quality, hilarious show that’s still airing today (or, if Reitman and cowriter Gil Kenan secretly think SNL sucks, to crystallize its squandered potential). Instead, the sturm und drang of shouted confrontations, briskly wheeled costume racks, backroom crushes, cut-for-time disappointments, a glimpse of half of Milton Berle’s cock, etc., culminates in a dutiful reenactment of the thuddingly mediocre “Wolverines” sketch that was the curtain-raiser on the real show.

“Wolverines” opens with writer Michael O’Donoghue (Tommy Dewey) sitting in a chair reading a book, when John Belushi (Matt Wood, in a slanderously grotesque portrayal) enters as a generic “foreigner” complete with baguette-topped grocery bag. Apparently, he’s there to receive English lessons, and the strange sentences he’s asked to repeat involve the title carnivore. O’Donoghue suddenly keels over from a heart attack, an action which Belushi cutely mimics. Then Chevy Chase’s stagehand wanders in to say the famous first “Live from New York…” It’s an amiable shrug of a sketch that, in fairness, may have served more as a throat-clearing to firm all the sound levels and technical details, but its laughlessness might prompt viewers to wonder what all the strident reverence of the preceding 100 minutes was about. While Reitman successfully depicts a high-strung evening, he lacks either the courage or skill to demonstrate why anyone should care about the show as anything more than the assembly line that would go on to give us Pat, Gilly, and Mango. —JS

“Is This a Film?” Award: Rap World

In Conner O’Malley and Danny Scharar’s debut feature, Rap World, set on the cusp of Obama’s inauguration, three residents (O’Malley and co-writers Jack Bensinger and Eric Rahill) in Tobyhanna, Pennsylvania, proclaim themselves rappers. Yet it’s clear that they don’t possess the lyricism or talent to be hip-hop artists. They spend more time at parking lots, parties they’re not invited to, and on road trips than recording an album in their makeshift studio. Shot on consumer DV cameras, Rap World boasts a “making-of” bonus feature aesthetic, the directors constructing their narrative outline as a mockumentary. The feeling embedded in these devices’ unpolished look elicits suburban nostalgia. O’Malley’s work should be considered cinema, but there are guard-rails keeping it from being widely seen this way. After Rap World sold out several festival and roadshow tour screenings, O’Malley uploaded it on his YouTube channel before the presidential election, receiving an age-restriction from the site’s content moderators. Though it is common for O’Malley to face censorship regarding sexual gestures or profanity-laced graphics/titles, this classification hinders Rap World’s visibility through the site’s recommendation algorithm, limiting the proper assessment of the comedic auteur’s channel as cinema. —Edward Frumkin

The Ridley Squat Award: Gladiator II

Who would have thought the wan follow-up to one of the least memorable and silliest Oscar winners of the 21st century directed by one of the most overrated studio shills of our lifetimes would feel like impersonal, rehashed, lukewarm réchauffé and leave Oscar prognosticators wondering what went wrong? Who could have seen this coming from the director of awards also-rans All the Money in the World, Kingdom of Heaven, House of Gucci, and Napoleon? Let’s hope that the world doesn’t stop wanting to honor this paragon of mindlessness so we can keep getting annual Oscar conversations around middling, overbudgeted never-camp-enough schlock. To the irascible filmmaker’s credit, he seems barely interested himself, so maybe we can follow his noble lead. —MK

Temporary Movie Resuscitator: Lesley Manville in Queer

Definitive Movie Executioner: Selena Gomez in Emilia Pérez

Cultural Illiteracy Award: Maria Stans

After Angelina Jolie failed to score an Oscar nod—thus stopping Pablo Larraín from going three-for-three for his interminable famous-rich-women-in-peril trilogy—her X-verse fans came out in force to proclaim their astonishment. A presumably young user/awards bot from the UK self-described as “angry feminist gayness films oscars race Princess Diana and fun” has so far secured 35K likes for posting “I’m genuinely so confused because angelina jolie really did this.” The fastened clip below shows what it is that Jolie “really did,” which is . . . lip synch to Maria Callas with a tear-stained face. One might assume, with benefit of the doubt, that the person who posted this is referring to Jolie’s ability to emote in close-up while mouthing to one of the most recognizable operatic voices in recent human history. Well, no: one of the hundreds of responders (“Pot-Smoking Slut in a Church Dress”) asked, agog, “SHE ACTUALLY SANG IT?!??” The original poster responds: “Yep.” Well, nope. Though there was some mixing of Jolie’s voice into certain scenes, especially those when she’s croaking or breathing with more labored effort, that very, very, very clearly that is the voice of Maria Callas. Judging by many posters (thousands?) seem to believe that Angelina Jolie “learned to sing like Callas” in a matter of months. The derangement of disinformation on the web is always somewhat more legible when you remember that most posters are actual teens, but the idea that Callas’s inimitable soprano can be recreated by a movie star’s sheer will for a crummy biopic pushes past ignorant Oscar idolatry into the realm of insanity. —MK

Sign of the Times: December 13–19, 2024

Casually perusing the top ten movies at the American box office in mid-December, as one does, I couldn’t help but notice this eye-catching lineup. 1. Moana 2. 2. Wicked. 3. Kraven the Hunter. 4. Gladiator II. 5. Interstellar. 6. The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim. 7. Red One. 8. Pushpa: The Rule – Part 2. 9. The Best Christmas Pageant Ever. 10. White Christmas. In case one ever needed a sign that the act of moviegoing as we once knew it is dead, take another gander at this list of titles, all released in the once prime movie real estate of December, when studios used to release prestige awards contenders and holiday blockbusters in tandem. I express this not to make some great claim for long-lost Hollywood respectability: a quick peek at the same December weekend 30 years ago reveals a fairly useless blend of second-tier rom-coms (Speechless, Junior); crummy thrillers (Disclosure, Drop Zone); sequels, remakes, and reboots heralding the era of IP domination (Star Trek: Generations, Miracle on 34th Street, Richie Rich); and one Jim Carrey gross-out (Dumb and Dumber). There was even a re-release of sorts: The Lion King—the actual one!—brought back to theaters for one last hurrah after its domination that summer.

This 2024 roster is a whole other matter, a fascinating motley assemblage of movie-shaped objects that reflects the astonishing and rather depressing disconnect between what critics cover and care about and the global buffet of differently sized spectacles that people are paying to see in theaters. Here at Reverse Shot, for instance, we reviewed only one of these movies . . . in 2014. Other than Nolan’s re-release, we have an animated sequel rescued at the last minute from a Disney+ streaming fate; a long-gestating, years-on-the-shelf Marvel spinoff from the director of Margin Call; an anime epic based on characters by J.R.R. Tolkien; a Jake Kasdan Christmas action-comedy starring The Rock that looks entirely AI-generated; a 200-minute Tollywood sequel; a holiday hit independently financed by a Christian film company; and a Fathom Events rerelease of a readily accessible 1954 Technicolor musical. Compared to these, the mega-budgeted Broadway adaptation Wicked seems like a model of scrappy can-do. Not much more needs to be said, just that ever so occasionally turning one’s attention over to what’s actually making money might be useful in understanding what 21st-century eyeballs are being drawn to and why. And, by extension, what a publication like this continues to fight for. —MK