Deliver Us

By Michael Koresky

Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood

Dir. Quentin Tarantino, U.S., Sony

Movies can’t save your life. They can’t change the world. They often can’t even live up to our expectations of what a movie should be.

Movies aren’t alive; however, they do outlive us. They capture reality for posterity, but they also capture dreams. This is why orthodox rules and strict ideologies about what film is or has to be are always bound to disappoint. If you come to a film with a definitive lesson plan in mind, then the film often has something unexpected to teach in return. Movies are real, movies are fake; they’re wishes, they’re nightmares. This paragraph isn’t meant to be a paean to the glories of cinema, just a stating of the facts.

Quentin Tarantino is in the movie business, and it’s a business he believes in with great affection. One can assume he knows it’s an outmoded affection, because his latest film, Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, is especially overcast with melancholy and fueled by a rueful self-determination to overcome it. It’s on the surface his simplest film, but somehow his trickiest to talk about. It jumps off the screen with life, even while all around it hovers the stench of death. It embraces movie stardom, even while it acknowledges the end of movie stardom as we’ve known it. It’s a work of exhilaration and sadness, generosity and sadism, naiveté and sophistication, fueled by an intense longing for a fabricated past that movies can only pretend to gift us.

By narrowing his scope to just three main characters, Tarantino allows them and us to luxuriate in this possible place, a scrupulously recreated 1969 Los Angeles that nevertheless somehow feels as heightened and surreal as the interiorized cityscape of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood is constantly negotiating between registers—between what’s real and what’s fake and why that doesn’t matter and why that really matters. Real people mingle with fictional characters; historical situations bump against invented ones. It’s riddled with pop cultural detritus of varying degrees of authenticity: billboards for actual movies like Michael Sarne’s Joanna and William Wyler’s Funny Girl cling to the sides of city buildings, but a framed poster of something called Jigsaw Jane, starring Suzanne Pleshette—not an actual movie—decorates an apartment wall; a vintage TV Guide cover exclaiming “Television in Turmoil” is seen shortly before a fake MAD magazine, boasting a caricature of the protagonist of the film we’re watching, fills the screen.

The people we see onscreen are not caricatures, but they’re approximations, most remarkable as physical specimens. As much as any living popular American filmmaker, Tarantino loves to watch humans move through space. In Pulp Fiction, Bruce Willis took a full minute and a half of screen time to get from his motel back to his apartment to find that gold watch while trying to avoid Marcellus Wallace. In Death Proof, Sydney Poitier luxuriously and surely moves across the dive bar and out to the rain-soaked porch; she’s doing nothing more than texting a potential paramour, but her formidable presence is enough drama for ten movies. In Once Upon a Time, Tarantino devotes his film to perhaps more down time than ever: his characters are seen driving, walking, watching TV, and, even, in one scene, reading. The accumulation of all this mundanity both allows us to inhabit an unusually paced rhythm of life and generates its own kind of suspense—when will something happen?

For its first two hours and change, the film charts the low-key perambulations of three characters over the course of a couple days in February 1969: Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), a B movie and TV actor in the Robert Conrad/Ty Hardin mold whose star is on the wane; Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), Rick’s former stunt double and best pal, who’s now employed by Rick mostly to drive him around and do odd jobs; and up-and-coming movie and TV actor Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), who has recently married her Fearless Vampire Killers director Roman Polanski, with whom she’s moved to Cielo Drive in the Hollywood hills—right next door to Rick. By having one real-life figure alongside two complete fabrications, Tarantino immediately sets his film in a strange register, never allowing viewers to completely get their bearings. Our knowledge of what happened to Sharon Tate obviously hangs like a shroud over most of the film: it’s not unfair to assume that Tate is mostly remembered by the American public for her shocking death, as a victim of one of the grisly home-invasion murders perpetrated by the Manson “family.”

Once Upon a Time is partly motivated by the drive to bring her back to life, though first and foremost, it seems, as a screen image. There’s certainly something jarring about Tarantino so prominently featuring a main character with so little to say, especially for a filmmaker whose narratives rely so heavily on loquacious protagonists. Since she was the only one of the film’s three prominent figures who actually existed in the world, this makes a certain amount of conceptual sense—it doesn’t presume or project very much onto Tate—yet it can also come across as a paucity of imagination for a film in which, really, anything goes, especially when she’s mostly relegated to dancing in her bedroom or driving the streets with a blissed-out smile on her face. Tarantino and Robbie are on their best footing with Tate during the character’s centerpiece sequence: during one lazy weekday afternoon, she impulsively ducks into a theater for a matinee of The Wrecking Crew, in which she costars opposite Dean Martin and Nancy Kwan. Taking clear, infectious delight in seeing herself on the screen, Tate settles in, puts her feet up, and surrenders to the screen. Tarantino opts to show original, unaltered clips of the film starring Tate herself. It’s worth remarking that in just the previous scene, Tarantino had made the decision to integrate DiCaprio digitally into a clip from The Great Escape, as a way of fancifully expressing what might have been had Rick landed the role instead of Steve McQueen. Tarantino thus tampers with an enshrined classic, but then immediately after maintains the integrity of a much less reputable B-movie, and it’s a fruitful choice. The incongruity of seeing Robbie look at Tate performing on the screen creates a productive ontological tension and a moment of generosity: we see Robbie as Robbie, a working actor, admiring and appreciating the slapstick craft of Tate, another working actor.

There’s little difference between a working actor and a movie star in Tarantino’s film. Also on February 8, at the same approximate time that Robbie-Tate is enjoying The Wrecking Crew, DiCaprio’s Rick is doing his best to stay afloat on a film shoot for a TV western. He’s playing another in a long line of “heavies” he’s been relegated to following his fateful decision to leave Bounty Law, the long-running series that made him a star, and which was canceled after his departure. Near the beginning of the film, Rick’s career had been surmised by Al Pacino’s savvy producer Marvin Schwarzs—“not Schwartz”—as entering its twilight phase, which has understandably shaken the actor’s confidence. Already on the edge, and having had his driver’s license long ago revoked for drunk driving, Rick is a bit on the rocks during the day’s filming, still recovering from last night’s eight whiskey sours. DiCaprio expertly performs Rick’s constant precariousness, with Tarantino’s lovingly recreated saloon confrontation—elegantly lit and tracked by DP Robert Richardson—always in danger of being fouled up by a forgotten line or a dialogue flub. Emotional and potential career redemption comes in many forms, in one case through the unlikely confidence boosting of his method-acting kid scene partner, eight-year-old Trudi (Julia Butters), whom he meets during downtime between shots. Initially Trudi seems like a parody of a wiseacre child star—she talks of needing to “avoid impediments” to her craft, demanding to be called by her character name, but ultimately she inspires Rick with her perspicacity. Asking Rick to explain the plot of the pulp paperback he’s reading, she listens with empathy as he relates the tale of “Easy Breezy,” a has-been bronco-buster suffering from a career-threatening injury. Though she, on the other hand, is reading up on the genius of Walt Disney, she thoughtfully closes her book and approaches an emotional Rick, knowingly engaging with him on the level he might best respond to: filtering his own experiences—his own fears and anxieties—through those of a fictional surrogate.

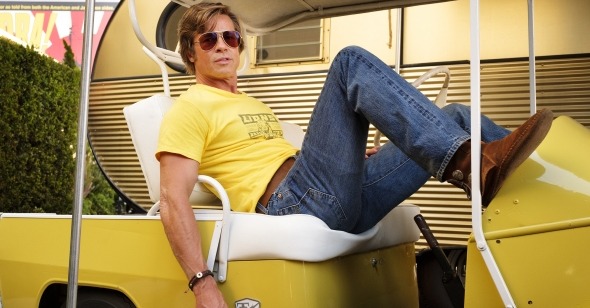

Like Robbie’s Sharon Tate and DiCaprio’s Rick Dalton, Pitt’s Cliff Booth is a performer on the fringes. In a way the most invisible of the three, as his screen stunt work was contingent on being not seen, Cliff lives a lonely but seemingly content life in a mess of a trailer behind the Van Nuys Drive-In, subsisting on boxes of powdered Kraft Mac and Cheese, his only companion his pit bull, Brandy. Everything about Pitt’s laidback Booth is an enigma: could he really be this satisfied being relegated to doing housework for a bigger star with a huge house in the hills? What did he do to end up on a Houston chain gang so many years ago? And, most disturbingly, are those rumors that he killed his wife—seen in brief flashback played by a nagging, soused Rebecca Gayheart—actually true? The film seems so intent on making Cliff a loveable, denim-clad hero—a real guy’s guy—that it’s both distressing and intriguing that Tarantino wants to frequently complicate our response to him. Then again, are we being asked to see Cliff Booth or Brad Pitt onscreen? There’s nothing complex about the admiration we’re meant to feel for Pitt’s 55-year-old physique in a lovingly gratuitous image of the actor doffing his shirt to do some afternoon work on Rick’s rooftop antenna—in that moment, character intentionally falls away and we’re left with an image of a movie star, someone fleshly yet impossible, a romantic ideal. When just a few minutes later, in a flashback, Cliff is accused of being a “wife-killer”—a claim that Rick refutes—it feels like a betrayal; can’t we just enjoy our movie star as a movie star? That these things are never reconciled gets to the heart of the essential disillusionment that defines the viewer’s relationship to stardom.

Cliff’s brutality first fully flowers during an extended set piece at the Spahn Movie Ranch, the rundown former B-movie backlot where the Manson Family set up shop in 1968 and 1969. Drawn in by a flirtatious free spirit (Margaret Qualley) who has hitched a ride with him back to the compound, Cliff has arrived there during the same span of time that Rick is filming the show and Sharon is watching the matinee. Having worked at Spahn many times back in the day, Cliff is intrigued and more than a little concerned that the place is overrun by what his boss Rick would call “goddamn fucking hippies.” Demanding to see the ranch’s longtime owner and his former colleague, George Spahn, Cliff ignores the mocking protestations of the commune’s bedraggled members, who’ve amassed on either side like old west townspeople, and struts down the center of the dusty road—the forthrightly artificial movie set has become a site of “real” danger. Despite a standoff with the group’s formidable, filthy ringleader Squeaky (Dakota Fanning), who tries to stop him from entering the dilapidated home where she seems to be either watching over George or keeping him prisoner, Cliff finds George (Bruce Dern) ambiguously well, if touched by blindness and dementia. It’s a tense yet bizarrely rambling side note of a scene, building to a climactic bout of violence in which Cliff discovers that the tire of his boss’s Cadillac DeVille has been slashed with a jackknife. As a result he convinces the jack-o-lantern-faced perpetrator (James Landry Hébert) to change the tire by pummeling his face to a bloody, bone-crunching pulp. For a moment, old-west lawlessness reigns, Cliff’s outsized retribution against the goofy longhair hinting at violent physical abilities that exceed the necessary work of a movie stuntman.

Pitt and DiCaprio, two of the last great American movie stars—both still plugging away as the industry moves further into franchises with interchangeable, constantly regenerating actors—feel fragile throughout Once Upon a Time. They’re perfectly cast in a film set in Hollywood at the end of an era. Yet Tarantino’s brand of poignancy is not to let them ride off quietly into the sunset. Apt for a film that’s so enamored of western genre conventions, he instead gives them one last chance to prove their mettle and save themselves from the dustbin of obscurity. Tarantino jumps ahead six months; Rick and Cliff have returned home to L.A. from Italy, where Rick’s been shooting a spaghetti western for Sergio Corbucci, under the recommendation of Schwarzs. Only an understanding of the significance of August 8—the date shown onscreen—would help the viewer know for sure that this was the final day of Sharon Tate’s life, though the police-report-like detailing by the narrator (Kurt Russell) of the night’s prosaic events gives us a pretty fair clue of what’s to transpire.

Having faith that his viewers need no more knowledge than this, Tarantino generates an odd kind of non-suspense, crosscutting between increasingly inebriated buds Rick and Cliff, getting wasted during one last hurrah before they officially break professional ties, and an eight-months-pregnant Sharon and her friends Jay Sebring, Wojciech Frykowski, and Abigail Folger meeting at a Mexican restaurant before returning back to Sharon’s house for the night. It’s here that Tarantino’s project reveals itself as in keeping with the historical revisionist revenge narratives of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, albeit without the knotty invocation of genocidal atrocities. Thus far, Once Upon a Time has been a mostly pleasant excuse for pushing American narrative moviemaking up against the limits of formlessness, as well as the welcome indulging of its maker’s pop cultural nostalgia. In the final act, Sharon disappears from the narrative, her life and the lives of her unborn child, as well as Jay, Wojciech, and Abigail—the actual victims of the Manson killers—saved due to the unsolicited, almost accidental interventions of Cliff and Rick. With this twist, a long, vaporous film prone to drift, during which the audience is invited to wait for something to happen, reveals itself to be about an event that never happened at all.

He’s subverting reality, but Tarantino has still happened upon a wholly traditional, masculinist conceit. Sharon Tate, ever lodged in the collective American consciousness as a victim of unimaginable cruelty, here is reconfigured as an unknowing damsel in distress. She is kept entirely off-screen, relievedly safe and sound while next door Cliff and Rick become lawless heroes, laying grisly waste to the three Manson minions. Instead of Polanski’s house, they have arrived at Rick’s, knives and pistols in hand. The “piggy” in their crosshairs is the TV action star they grew up watching; they want to send a message, as Mikey Madison’s murderous Sadie puts it, “Kill the people who taught us to kill.” The resulting sadism meted upon the three would-be killers—it must be stressed that in the narrative world of the film, they haven’t killed anyone, as far as we know—is pushed to such an extreme level that it’s impossible not to recoil from the presumed catharsis, especially when so much of the gleeful mutilations happen to women. Their bodies are chewed apart by Cliff’s trusty pit bull, their faces smashed and bashed beyond recognition, and, in one case, fatally charred to a cinder. Tarantino gives you what you think you want to see, but when the violence gets too real—the events too fake—he almost immediately makes the release feel disreputable.

Despite the film’s many chill soundtrack cues—its expertly placed Neil Diamond, Chad & Jeremy, and Paul Revere & the Raiders songs—it’s Sadie’s horrified squeals of incredulous pain and fury that finally overtake the film, the sound that most lingers. In the absence of the Manson murders as we’ve known them, do the deaths of these three instead become the received narrative of “the end of the sixties”? Or would that be the killing at the Altamont Speedway, which would happen in just a few months? Either way, the U.S.’s involvement in the Vietnam War would still be going on for years. Here, Tarantino isn’t out to change the larger course of history so much as use cinema to mete out a kind of cosmic retribution, as he had done in Death Proof; in that film, his variation on the rape-revenge genre, a group of women take appropriately violent revenge on a sociopathic stuntman, without knowing what we viewers indeed know: that he had killed an entirely different group of women in the film’s first act.

Knowledge is key in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood. We bring history with us into the theater; otherwise it’s completely illegible, a movie that spends a lot of time following around that woman next door who, thankfully, had nothing to do with all this messy business. What we know—about what really happened—makes Once Upon a Time satisfying; and what we know also makes it indescribably sad. It’s an impossible movie, and a movie about impossibility. Is Sharon Tate the film’s heart or its void? Can she be both? Tarantino has made a primal, powerful film that’s difficult to square; it’s hard to know what emotion to take with you when it’s over. This is also what keeps it lingering in the mind. Its opening credits come up over a painting of a mouth in such extreme close-up that one can’t tell if it’s smiling or grimacing. By the end, I felt the same way.