Golden Arches

The World meets The Terminal

By Michael Koresky

For years we at Reverse Shot have been quite vocal about our desire for representations of the “now” in contemporary film, and perhaps even more vociferous when we discover the dearth of such attempts. This does not necessarily apply only to Hollywood, one of today’s great socially reductive oligopolies; foreign cinemas have been just as hesitant to tackle or even try to comprehend the constantly shifting yet steadfastly baffling and decentering glut of today’s moral, political, and technological tangles. For every great, forward-looking rumination like demonlover, there are 10 more like The Motorcycle Diaries, cloaking their middling social commentary in the gauze of nostalgia and crowd-pleasing dramatic irony. But what is it that we’re really looking for? Is it a reflection of where we see ourselves, or what we’re trying to attain? It’s become commonplace to decry the moral dissolution of an increasingly globalized society in which we’re all one mouse-click away from each other, yet we are the builders of our own, newly hermeticized moral universe. Nothing seems to contain just itself any longer, to be satisfied with merely its own connotations; there’s a sort of a six-degrees-of-Kevin Bacon-gaming of the world going on. Or at least current economic width allows for more of a reading. The simple act of ordering a Fillet-o-Fish and a small fries on the McDonald’s at Broadway and 8th now dredges up a global web spreading its tendrils all the way to Beijing. Surveillance paranoia is a thing of the past; we live and breathe information, spewing and intaking chatrooms, blogs, mp3 downloads, endless newswire streams, cell phone text messaging; we invite interruption, we thrive on constant penetration, and interpersonal connections are now dictated by global corporate hierarchies.

Within the bat of an eye, a free market can become a black market, if supply and demand requires it. What this means to the ever-expanding global community is rarely tackled onscreen; however, over the past year two candidates stepped forward, and with wildly varied degrees of success, threw their hats into the ring to look at the implications of the term “international community.” In “our” corner, the most complex figure in American Hollywood cinema, the rarest specimen, a true moral and visual artist so caught up in Hollywood’s suffocating mechanism that he often capitulates to its whims, despite his best efforts: Steven Spielberg, with The Terminal. In “their” corner, one of the great shining beacons of contemporary Chinese cinema, a constant surveyor of his country’s slow emergence into a “free market” economy, and the current expert proprietor of dramatizing the global dilemma: Jia Zhangke, with The World. Old-guard vs. new guard, the Western purveyor of global dominance versus the Eastern standard-bearing representative of economic groundlessness. Both of these filmmakers look at the Wal-martization of the working classes and its relation to our xenophobic tendencies, exporting their ideas by utilizing large and burdensome simulacra—a stunning, playground reimagination of JFK International Airport in Spielberg’s case; a theme-park recreation of the world’s various cities and landmarks in Jia’s case. Each director’s gigantic metaphorical structure, one built from the ground up, the other an existent place, is meant to contain all the world in its microcosm. Even more important to note, though, is how one fails miserably while the other follows through to the end of its inexorable vision. And it’s not simply optimism versus fatalism but a fairly complex example of Western obliviousness to Eastern (Eastern-European in the case of The Terminal) trickle-down consequence clashing with Eastern suspicion of Western supremacy.

Is globalization phenomenon or myth? Jia Zhangke asks this in nearly every frame of his hi-def opus, a stunningly plus-sized work The World, filled with very intimate exchanges and populated by very small people harboring no delusions of grandeur. Like in his previous film, Unknown Pleasures (2002), Jia wishes to dissect a contemporary way of life through tiny gestures and daily ritual. However, as it’s set against the backdrop of the World Theme Park, an imposing series of smaller reconstructions of other corners of the globe, there’s no mistaking the film’s wide-ranging intentions, its savvy simultaneous expansion and minimization of contemporary life. “See the world without ever leaving Beijing!” cheerily announces a voice on the loudspeaker as The World’s protagonist, the dancer Tao (Zhao Tao), shuttles between artificial provinces on a monorail. “Famous sites from five continents for your pleasure.” Indeed, the World Park is a dizzying conglomeration of the globe’s greatest hits—Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Sphinx, the Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triomphe, Taj Mahal, Moscow’s Red Square—yet it’s also slightly ramshackle, askew, and disorientingly half-realized in stature. Not too far removed from Western destinations such as Florida’s Epcot Center or Las Vegas’s numerous, overbearing recreations of other tourist destinations, the World Park, as it exists in Beijing, is a way of comforting its inhabitants with a false sense of adventurousness.

As a result, its inhabitants, mostly those workers who have come to Beijing from outer provinces in search of jobs, are themselves muddled amalgams: Tao is first seen in a jade-green Indian sari, elaborate nose-ring extended to her ear with a chain. Jia’s style, to shoot in reserved long takes, often from greatly detached angles, literally dwarfs his actors within their environments, even within their own private spaces. (A quiet moment in bed between Tao and her security guard boyfriend Taiseng in her cramped apartment, the room suffused with a dull amber glow, is shot at such a calm remove that their intimacy can be viewed as either ominous or erotic, depending on your emotional involvement.) The World is Jia’s first film to focus solely on the city, although his prior takes on the urbanization of mainland China, and particularly his native Northern Shanxi province, were wholly informed by burgeoning city mentality. Now that he moves his setting to Beijing, ironically things feel smaller than ever; as the world is opening up, his characters are becoming ever more closed off, the obvious corporatist agenda of World Park feeding on every facet of the increasingly credit-based economy like a germ. The introduction of a group of displaced Russian emigrés adds to the polyglot horror of his scenario: despite Tao’s best humane efforts, Anna (Alla Chtcherbakova) ends up a piece of damaged trade goods herself, forced into prostitution to regain her passport and therefore identity.

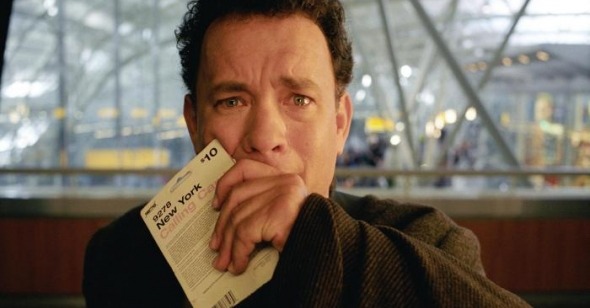

In his own version of Eastern European commerce and human trafficking, Spielberg sets up a visual palette in complete opposition to Jia’s, although they both initially manage to create astonishing platforms on which their fishes-out-of-water can flop around in 21st-century disorientation. Within 20 minutes, Spielberg establishes the aerial gateway to the U.S. as a kingdom of pop-cultural excess (indoor malls stacked with Starbucks, Borders, McDonalds, Foot Locker, all piled on top of each other in a frighteningly queasy Pisa-like tower of corporate precariousness), xenophobic fear-mongering, and homeland defense hysteria. As in The World, almost all of the film’s running time stays within the confines of its simulacrum, here an airport terminal where Victor Navorski (Tom Hanks), the vacationer from the fictional, civil-war-torn country Krakozhia, is trapped until a governmental loophole is sewn up.

Spielberg relates all of this with a flurry of images so incisive and commanding that the subsequent drop-off in sociopolitical insight is a shock to the system. Both films portrays the language barrier initially with delicacy; barely understanding English, Navorski reduces his speech to a nonsensical litany of yeses and nods, while Anna, desperate for contact, happily befriends Tao, although all she can do to communicate is show photos of her children and gesture to Tao’s ring-finger to inquire whether or not she’s married. The gap, however, is not as easily overcome for Anna and Tao as it is for Navorski, who learns an absurdly fluent English by browsing through Borders’ paperback translation dictionaries. By so easily acclimating to Western modes of communication and commerce (Navorski, adorably, uses his adept language skills to land a job and work his way up the fast-food ladder), Spielberg creates a hearty justification of the internationalist tendency that the film initially seems to question.

The irony is so thick it all but corrodes the screen like acid: The Terminal’s saddening, disconcerting reemergence into the safe Capra-esque world of meet-cutes, last-minute rescues, and tidy psychoanalyzing makes an even more perfect case for severe capitalist capitulation than the entirety of Jia Zhangke’s The World. In trying to bear witness to the West’s global cultural dominance, Spielberg crawls right back into the Hollywood structure’s death grip. Always too focused on making his audiences happy and not having the requisite distance from studio ethics to realize that his most successful films have been those that have either challenged the status quo (A.I., The Color Purple, Close Encounters) or resisted simplistic political readings (1941, Minority Report, Empire of the Sun, Amistad), Spielberg betrays his own social humanism in a greater manner here than ever before by not following through on his initial revelations. Giving his audience what he thinks it wants, he ends up making The Terminal into a pretty damn near perfect example of ever-diminishing returns from applying supply-and-demand ethics to cultural products. And with Jia’s film, the whole structure collapses, but this time it’s the screenplay that crashes down around everyone, as with The World’s Tao and Taiseng, bereft and hollow ciphers, victims of corporatist agenda and artistic compromise.

On the terms of its own failure, The Terminal is even more of a cry for help than Jia’s melancholy lament, if you can just make out its pleas behind its suffocating layers of Screenwriting 101 refuse. Both films are fairly sophisticated in their views of human containment; as the world expands, things simply get smaller and more claustrophobic. Both films dare to ask: What’s outside these environs, these self-made walls of capitalist dominion? Yet they come to wildly different conclusions—Spielberg’s vision may be refreshingly optimistic, but it’s also depressingly reductive; Jia’s portrait feels genuinely connected, yet it’s also surpassingly grim. In these times, what is desire? What is need? These twin impulses are more muddled than ever; The World questions the far reach of the West’s materialistic grasp, while The Terminal ultimately, perhaps inadvertently, champions it. In the end, Navorski is free to leave the terminal unimpeded, its cuddly multi-culti staff looking on with heads cocked to the side as their adorable foreign friend walks off into a charming New York winter wonderland to get the signature of the jazz musician his father so loved. Similarly, The World also ends in the snow, yet in a blizzard of grief—the world has shrunk even further, trapping its inhabitants in an ice tableau of frozen debt and unsustainable growth.