Hopelessly Devoted to You

Nick Davis on Possession

Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession has the feel of something produced by a coven, not a crew. It’s the kind of movie envisioned by all those obsidian novels about occult cinema, your Nightfilms and your Zerovilles, though nothing can equal the direct experience of such unhinged impulse and imagination on screen. An infamous target of worldwide censorship, Possession isn’t just “designed to provoke,” a goal that often relies paradoxically on familiar scripts. We’ve all seen plenty of work by artists keen to set us squirming, pushing the very buttons we expect them to push. It’s much rarer to sense each member of a creative confederacy testing their own most dangerous limits, jumping onto the tracks and licking that third rail. It’s rarer still for that charge to feel undimmed after four decades.

Part of Possession’s dark power inheres in its slippery, tentacular relation to its own genres and themes. Repeatedly, the film lunges at an idea or stakes out a tone, each offering plenty to chew on, but then pounces just as fiercely in some transverse direction. You sense this madness right away. The earliest images are establishing shots of the Berlin Wall, circa 1981: an endless segmentation of cadaver-colored slabs, lying across the city like a concrete worm. On the muddy, weedy Eastern side, Y-shaped poles of jet-black iron run parallel to the Wall. Already, this second line of defense stands denuded of its razor wire, implying a border that—like every formal and conceptual boundary in the movie—is already mid-collapse.

This opening sets the table for a Cold War political allegory or a dark ethnography of a bipolar metropolis. Almost immediately, though, Possession regrounds its narrative in personalized terms. Mark, a husband and father played by an antic, reptile-eyed Sam Neill, hurtles in a taxi toward a West Berlin apartment complex. In crosscuts, his wife Anna bounds aggressively through the courtyard of that same complex. Anna, we’ll soon discover, is the demonic queen in Isabelle Adjani’s long line of firebrands and ferocious sufferers. For now, the handheld camera barely keeps pace with her until she’s face-to-face with Mark on the sidewalk. Each speaks at a high, nervous pitch exacerbated by Żuławski’s sound mix. Mark mostly has questions: What do you need? When will you know? What has happened?

Already, Possession’s viewers harbor plenty of our own questions, and we’d better get used to that feeling. Are Anna and Mark divorcing? Are they reconciling? Are they trying to salvage a home life for their towheaded son? Are they aware that no phoenix will rise from the ashes of their union? Yes, yes, yes, and yes. Side-by-side in bed, shoulder-to-shoulder for one of the only times in the film, husband and wife offer guilty confessions and quasi-apologies: his regretful yet resentful, hers panicked and despondent. But nothing takes, and Anna’s denials of infidelity hang limply in the air, further undermined by her sudden, serial disappearances. Soon, Mark and Anna are seething in a café, negotiating access to a child they both love but whom neither prioritizes. They sit almost back-to-back until tempers explode, scene structure collapses, and the actors—scrawling well outside the usual lines of “staying in character”—start flinging furniture at each other. When next we see Mark, he’s three months into a sweaty, jaundiced delirium: perhaps a plunge into addiction, but just as plausibly a drastic withdrawal. When next we see Anna, she’s darting home from another tryst, presumably pleasurable, yet she seems so psychically frayed that the camera cannot find a stable angle on her. Adjani careens into the lens, so close that we almost see the undersides of her eyelids.

Possession, an English-language freakout by a Polish auteur working in Germany with a pan-European crew, is never not about the unstable schisms among civic orders or between ideologies. It’s also never not about the uncontrollable affective magma released by divorce, especially when a chauvinist man feels humiliated by an unfaithful wife. Few films execute a more headlong dive into those boiling waters, but Possession is too dramatically and intellectually restive to commit fully to either, or to reduce political and marital breakdown into reciprocal metaphors.

Instead, you sense within 20 minutes, if not earlier, that Possession isn’t “about” anything so much as it is something: a channeling of uncanny energies that exceed any metaphysics of plot, exceed the most rococo explosions of action and feeling, exceed the most traumatic histories or overdetermined figures (e.g., the family, the Christ, the Berlin Wall). Edits truncate volcanic episodes just as their tops are blowing. Bulging, wide-angle frames consistently find two actors facing in opposed directions, or widen the gulf between foreground and background, or both. The portentous, John Carpenter–style surges of Andrzej Korzyński’s synth-heavy score, mostly immune to melody or resolution, produce even more agitation with high, quick piccolo trills and the scraping sounds of a wooden güiro.

Meanwhile, every small step forward for the story entails a giant leap in sensation, saved from folly by the sheer, humbling intensity of everyone’s commitment. Mark tracks down his amorous rival, an eccentric alpha named Heinrich who fondles and pummels him inside of four minutes. During that time, both men seem to grasp that Anna’s mysteries supersede either of them and overspill the tidy form of the love triangle. Shortly after, Anna has a howling breakdown and Mark beats her for it, leaving them both bloody in the street. She yells into the camera, a meter-long strand of red saliva dangling from her open mouth. Not much later, Anna purposely slices her neck with an electric carving knife. Mark cleans and bandages it like a child’s cut before testing out the same blade on his own forearm. Will the family that slices together stay together?

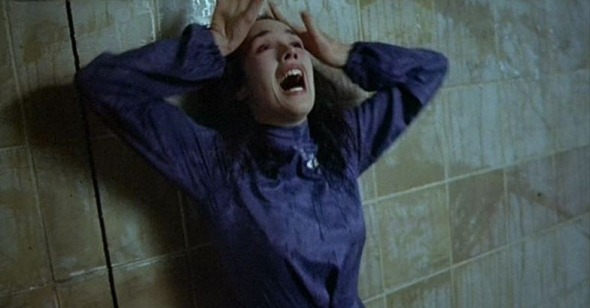

Possession continues to push envelopes with incident and pitch. I haven’t even mentioned the film’s most notorious reveal: that Anna’s amour fou is not with a person but with a squidlike slime mold. I also haven’t addressed the most famous and harrowing set-piece, Adjani’s three-minute tour de force of caterwaul and conniption inside an empty subway station. Its culmination looks for all the world like an extraterrestrial miscarriage but turns out to presage a differently monstrous birth. For both the film and the character, the sopping fluids and hellion screams of this sequence are a threshold into reinvention, not destruction. They herald not a sloppier, messier future but a disconcertingly clean and robotic one—give or take some more chaos and bloodshed en route, plus the escalating noises of unseen warfare on the soundtrack.

Throughout Possession, bodies, lovers, ideas, emotions, geographies, trajectories, and desires keep conjuring their putative opposites. In tone, shape, and story, the movie reels like a demagnetized compass, lacking polar coordinates or clear center/margin relations. A semi-legible conclave among white-collar workers in a dreary corporate office is for some reason filmed like a bonfire; the camera won’t stop spinning around it. By contrast, a sexual congress between a woman and a mucoid cephalopod—the tableau toward which the whole film has dreadfully advanced—barely raises the camera’s pulse before Żuławski cuts to a dialogue scene with a third-tier character. In single edits or across scene transitions, the movie both sustains its unrelenting crescendo and frequently reverses itself: a detective story where everything and nothing is discovered, a him-or-me ultimatum to which the answer is “neither,” a demure and doll-like species of drones hatched from a gyre of viscera and commotion, a story of yowls and tirades that is no less unnerving when plunged into quiet.

This propensity for sudden, uneasy stillness is the aspect of Possession you’re least likely to guess from my account thus far and offers further proof of Żuławski’s fearless, flexible sensibility. You can imagine the movie that would jump and jangle more as it approached its secret, its creature, its showdown. You can imagine the movie that, having conceived such an outré specimen as Anna’s ectoplasmic paramour, would make that figure its governing symbol, its emergence the crux of its plot or moral. Possession is neither of these movies. The scenes inside the dusty lair of the beast, where Anna is acolyte and concubine and guard, are notable for their hush as well as their slow, tense construction, as more and more men breach this corner-lot heart of darkness, positive they are the hero of this journey. The monster itself turns out to be a borderline MacGuffin: not a narrative end in itself, not an eruptive threat within one marriage, but a means by which humanity transforms in subtler, eerier ways. The logic and scale of that uncanny process emerge belatedly but clues have hidden in plain sight much earlier. To that extent, Possession is a test of where we place our attention, even or especially in tumultuous circumstances, and of whether we recognize menace and crisis when they take docile forms.

***

Possession is emphatically more than the film augured by its opening, and it well exceeds the events captured at its finish. Its middle contains many movies, and many experiments: a tale not of interpersonal but of ontological adultery; a post-divorce project that makes The Brood seem diffident; a pre-Perestroika prophecy of a post-Iron Curtain world, equal parts bedlam and conformity; a reframing of cinema not as a representational art form but as what Patricia MacCormack in her book Cinesexuality called an enterprise in “baroque becomings”; an intrepid recalibration of how cameras relate to bodies, and how bodies can be seen or directed to perform.

In this respect, Neill and especially Adjani, who won Best Actress at the Césars and at Cannes, must be credited as co-authors of Possession. Indeed, Żuławski embeds in his text the sense of Adjani as a privileged, conscious, yet fathomless source of the movie’s tremendous potency. An hour into Possession, Mark sits to watch footage someone has recorded of Anna leading a ballet class for young girls. What he sees, of course, is no decorous survey of Degas-style damsels. Anna terrorizes one of her charges at the barre, painfully bending her leg, arm, and back into barely tenable postures and demanding that she hold it, hold it, hold it. The irony is especially cruel, since the dancer visibly suffers as the actress has surely suffered in making this endlessly shapeshifting film, which has demanded much of its star while rarely holding any one pose for long. The girl’s mouth becomes an awful rictus, but no less disquieting are Anna’s direct gazes at the lens, at Mark, at us. She knows we see her doing this. She knows we’re here.

What ensues is a direct-address monologue, interrupted yet continued over some oddly edited shots, hard to parse as Anna’s ideas but clear and confronting when taken as the actress’s own testimony. She hails her viewer as a separate entity on whom she remains dependent, “as if I am an empty space… as if I need you to fill me up.” With palpable anguish, though of a less florid kind than Adjani conveys both earlier and later in Possession, she wrestles semi-coherently with notions of faith and chance. She imagines some “third possibility” that may name or mediate aspects of human (or other-than-human) experience that surpass chance or faith. I’m not sure these are the right passwords to unlock Possession’s enigmas, but the sense of conceptual dichotomies proving unstable and inadequate, and thus of seeking meaning in some ineffable, alternative term, is all too easy for Possession’s viewer to relate to. Meanwhile, at this core of a movie that has indentured Adjani’s body into such arduous service, it’s remarkable to hear her mind at work on this taxing piece—even if she grasps at straws, as we surely do.

This episode is almost unreadable in diegetic terms, especially since the images we behold no longer resemble in palette, film stock, setting, or rhetoric the film-within-a-film that Mark sat down to study. Possession seems to have shattered, Persona-style, revealing not a blinding-white void or a series of menacing gestalts but an actress, a co-author, very much present, giving voice to some thorny questions that this punishing movie might prompt in a zealously devoted, possibly too devoted performer. True or not, lore has swirled since Possession premiered about Adjani’s mounting fragility during production, about a suicide attempt soon afterward, about a pledge to never again accept such an unrelenting role. But must we understand Adjani as the film’s object, vessel, or victim, when she is at least as much its subject, engine, and voice?

Not least when she is pinned beneath that writhing alien, it is easy to imagine Adjani as equally under Żuławski’s thumb. Not least when she is spiraling, shrieking, and self-flagellating in the subway tunnel, it is tempting to conceive of Adjani, not just Anna, as a marionette, a conduit, a woman possessed: an actress in the Falconetti vein, working beyond her controllable faculties, giving even more than her director asks, which is already just about everything. But in addition to posing in this mid-film interlude the questions of an ambitious artist—one who uses her work to pursue, in her words, “something that pierces reality” rather than just “contorting reality”—Adjani exchanges gaze after gaze after gaze with Possession’s viewers. Some of these looks beseech us from somewhere close to rock-bottom. Others, though, are lucid, impassive, curious, conspiratorial, neutral, coy, even imperious. Imagine the woman at the bottom of the well in The Silence of the Lambs signaling in flashes that we needn’t worry, that we mustn’t underestimate, that she is just as much the captor, the detective, the diabolical genius.

The movie’s final image is of Adjani staring us down, albeit through literally new eyes. We may fear for the actress at times while watching Possession, but surely we also owe her our awe and, to some degree, our willing identification, no matter how bewildering Anna’s behaviors. “You say ‘I’ for me,” Anna/Adjani muses at the beginning of her cryptic soliloquy, raising questions about Possession’s point of enunciation and its governing power dynamics. We look so often into Anna’s and Adjani’s eyes as the movie unfolds. Just as often, we look through those eyes, in shots overtly framed from her POV. She admits her earnest and disorderly thoughts, briefly taking possession of the film to make sure they get heard. She asserts her presence and her agency, however qualified and untranquil.

Anna is the chronic focus of her husband’s, her director’s, and possibly her spectator’s baffled interrogatives: What has happened? What do you need? When will you know? Who are you? What on earth are you doing? But Żuławski’s wiliness with perspective, in tandem with Adjani’s magnetism in performance, ensures that we don’t just regard Anna and her interpreter as objects. We ponder their confounding but tantalizing subjectivities. We feel, in this most tactile and kinesthetic of movies, what Anna and Adjani might feel in their bodies—what their bodies are capable of doing or becoming. We sense ourselves joining ever more closely to a movie, a director, a character, and an actress so challenging and so “other” as to feel unknowable, unreachable, alien. And some part of us, maybe not a small part, savors this ecstatic experience.