The Massacre Is the Message

Suzanne Scott on Starship Troopers

Some six years after Paul Verhoeven gave us the beheaded reporter, CNN and FoxNews gave America the embedded reporter. Evolution? Hardly. Oft-cited Nazi allegory and meditation on the post-Gulf notion of purportedly “clean” warfare, Starship Troopers remains both relevant and revelatory in our currently tenuous post-quasi-war environment. Get past the bugs, the blood, and the boyish phobias (anyone who tries to deny the decidedly vaginal presence on the “brain bug” of the film’s climax should be locked in a closet with a copy of Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis), and Starship Troopers remains perhaps the most affecting commentary on the interaction between the fictional tendencies of the news media and the blunt reality of war. Serving as an intergalactic Greek chorus of sorts, the all-encompassing global Federal Network, a fictional amalgam of network and cable news, is woven throughout the film’s narrative in the form of reports, updates, and so on, all regarding Starship Troopers’s constructed war against the hostile Arachnid bug species of Klendathu (which, it should be noted, is a veritable melting pot of bug species....take that, all encompassing Other!). These brief and overwhelmingly cautionary glimpses into the evolving nature of our news media sets the film leagues apart from its giant bug-busting drive-in predecessors. Strangely enough, the warning is directed not at the potential savagery of future military conflict, but the increasing sensitivity of the news consumer for clean, compact coverage of inherently complex world events. “Would you like to know more?”

“Why We Fight”

The greatest irony of the current 24/7 media news cycle is its absolute lack of content. Not unlike the spacey soap-opera narrative arc that Starship Troopers constructs, war news has evolved (or, arguably, devolved) into an endless cycle of repetition and meager acceleration, promising resolution and never quite delivering. We are assured that victory is emminent, but it is never tangible, regardless of how many times the brain bug is captured and probed or the head of Saddam’s statue is dragged through the streets. The film’s Federal Network undoubtedly (borderline shamelessly) satirizes network and cable news conventions: the cacophonic war theme music, the now commonplace visual tropes of soaring eagles and fluttering flags, the omnipresent “live” reminder tag in the corner of the frame (because God forbid there be thought given to sociopolitical commentary), etc. Even the easily decipherable kiddie comprehension war maps appear, complete with the cribbed “You Are Here” format popularized by the American mall, to discuss intergalactic subject positioning. But perhaps even more interesting are the subtextual implications of what initially appears to be little more than blatant, albeit clever, parody. A retrospective glance at Verhoeven’s homage to Darwinian carnage serves only to enhance our reception and comprehension of the United States’ continuing militaristic endeavors (and, synonymously, news coverage of the modes of warfare). Starship Troopers is as unflinchingly violent as the Iraqi wars are sanitized; Federal Network’s frank depiction of the full brutality of conflict begs the question of what our current news media is, or more importantly, isn’t telling and/or showing us. “Would you like to know more?”

“A World That Works”

News tickers, streaming video, live feeds, web links: television news has truly embraced all that new media has to offer, resulting in the still-unfulfilled promise of viewer interactivity and, ultimately, content control. It’s no accident that FedNet (in and of itself titularly reminiscent of a website) is designed to resemble a network news homepage, complete with a spectral spectator guiding our digestion of Starship Troopers’s news with the visible click of a mouse. The film’s continual info-rally cry of “Would you like to know more?” is not merely a rhetorical question, it’s a commentary on society at large: past, present, and, in this case, future. We wouldn’t merely like to know more, the modern news consumer demands to know more. The news’ preoccupation with “liveness” (vampirically feeding off of the spectatorial paranoia of “missing something”) comes under close scrutiny in Starship Troopers. The public’s (real and fictional) ceaseless desire to be fed information takes on the apparent quality of media binging, with no purge in sight. There’s always more to know, thus there is more to fear, thus there is more to learn about what we have come to fear, and round and round the news ticker goes. What Starship Troopers promises, then, is a future where new media is no longer “new,” simply “media,” while simultaneously questioning what such technology has wrought, namely a news consumer who (much like the bugs themselves) is seemingly never satiated.

“Know Your Foe”

Iraqis. Arachnids. Coincidence? Not convinced? Bear with me. Federal Network, like many in a time of war, painstakingly creates an ideological construct that differentiates “us” from “them.” It goes without saying that the binaries of “right” and “wrong,” “good” and “bad,” correspond accordingly. FedNet’s analyses range from geographic concerns (we’re told immediately that the arachnids’ home planet of Klendathu is a bare, “ugly” desert wasteland) to various renderings of the bugs as savage and nonsensical. The initial and seemingly unprovoked meteoric bombing that rallies the humans to war is oddly reminiscent of the events of September 11th and how it was used to frame the American invasion of Iraq as the logical next stage in the war on terrorism. FedNet knows what its viewers want, and it delivers in the form of instant media gratification. Quick punishment for war criminals? FedNet promises trial and conviction on the same day, with execution broadcast live right in time for dinner. In-depth war coverage? The live-on-location cameraman keeps shooting after his anchor has been literally severed in two and as he himself is being disemboweled—now that’s dedicated journalism. War itself is never questioned within the film’s narrative discourse: bugs are bad; we’re good. We kill bugs, save the planet, Denise Richards rewards us with a smile, and all is again right with the world. The logic may seem initially laughable, but for those only consuming televised news, remarkably familiar. Except the poor schlubs watching CNN don’t even get that well-deserved smile.

“Join Up Now”

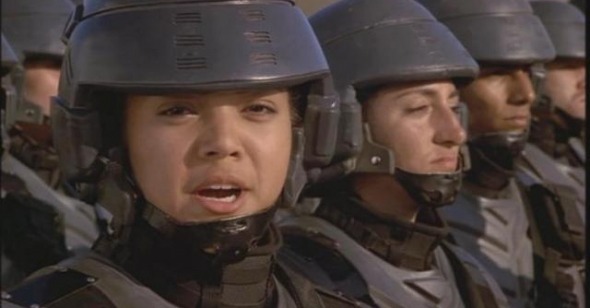

The film opens with a direct homage to the “Uncle Sam Wants You!” recruitment campaign, concurrently presenting its troops as a meticulous exercise in racial and gender equality (black, white, blonde, brunette, all chanting “I’m doing my part!” in a paradoxical instance of the unifying nature of individualism) and American superiority. If nationalism is the fuel that feeds war coverage, patriotism is its aesthetic dictator. While the faux news reports of FedNet regularly veer towards the propagandistic in terms of presentation (it seems that future societies have abandoned the grating subtlety of lowercase letters), their content is strikingly multifaceted. Coyly playing with issues of globalism and locality (or, more accurately, the universal and the planetary), Starship Troopers has constructed a planet Earth that is wholly populated by Americans. Aside from the perverse pleasure granted in hearing such clichéd war dialogue as “...the goddamn Bugs got us, Johnny...” being trotted out over the destruction of that tried-and-true U.S. metropolis Buenos Aires (who knew Doogie Howser was Latino?), getting all those pesky geopolitical lines wiped off the map makes perfect narrative sense. In addition to firmly entrenching the us/them binary (with no real nationalities at play, the viewer is forced to align with human or bug—hence, no confusing renaming of crepes as “freedom pancakes” to cloud judgment), the film’s central conceit of global “citizenship” as a reward for military service renders an entity like the United Nations useless.

To show or not to show, that is the question. The modern news media has essentially drawn the shades on America’s “window on the world” in its vehement disassociation of war and gore, a fact which Starship Troopers not only picks up on, but openly mocks and ultimately criticizes. This “if it bleeds (and is ripped end to end by giant predatory bugs), it leads” mentality that manifests itself so blatantly in the film is obviously an extreme, though one that is seemingly countered by our current media environment, in which death is conveyed only in statistical graphics. In the narratological construct of Starship Troopers’s portrayal of the news media, knowing is tantamount to showing. There’s something to be said then for the more viable form of journalism that the beheaded reporter represents. Though Americans’ thirst for knowledge seemingly does not extend to the depiction of reality as reality (thus the removal of such things into a safe, sci-fi context here), there is a purity to the news reports of FedNet that transcends not only the contemporary media but offers the promise of a restored sense of honesty. Imagine that. Informative news. Let’s hope we don’t have to wait for bug warfare for Starship Troopers to fulfill its promise.