Godard's 60s

Breathess

What does Godard mean to us in 2008? It's a question that's surely been asked, or could have been asked, in any given year since 1960, but it's one worth asking again now, certainly on the occasion of Film Forum's extensive retrospective, Godard's 60s, starting today and running through the beginning of June. And with Richard Brody's already acclaimed biography, Everything Is Cinema, hitting bookshelves the week after next, and the fact that we're currently "celebrating" (always an emotionally contradictory task) the events of May '68, now on their fortieth anniversary, it's obvious that Jean-Luc Godard is on a lot of people's minds these days (not that he's ever really gone). Yet when we talk of Godard, certainly in terms of post-68 France, we're talking about a cinema not just politically engaged but transformed into a medium for political confrontation: filmic missives that refuse to cloak their agenda in tangential details like narrative or character.

Godard's first film, then, was to always remain unlike any of those that followed; political only as it related to genre representation and the decimation of his beloved art form in the hopes of rebuilding something new in its place, Breathess was both a new beginning and a full stop. Even in his subsequent New Wave genre plays, like Alphaville and Band of Outsiders (whose "lightness" betrayed an increasing discomfort with their own rules and built-in hegemonies), he had already moved past Breathless, with its deceptively simple subversions that still relied on emotional interplay and cause-and-effect narrative strategies. The effortless casualness of Breathless (which by all accounts had been worked out to the minutest detail by Godard beforehand, despite the film's appearance of slapdash ingenuity) was to be so swiftly replaced by a harsher, more rigorous formalism that the film promptly became something of an orphan. Immediately following its buzzy Cannes premiere, in a May 1960 television interview, "Reflets de Cannes," Godard said, "I feel like I love cinema less than I did a year ago, simply because I made a popular film. I hope that people hate my second film so that I can enjoy making movies again. Audiences trust me now. I hope I disappoint them so they don't trust me anymore." Though Godard has changed his interrogatory political and aesthetic approach countless times over the years, this last statement still rings true to Godard's intentions—and if he ever begins to let audiences trust him, then his exhilaratingly confounding career would be as good as defeated.

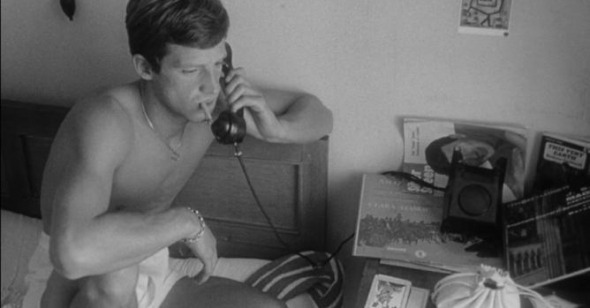

Maybe the more pertinent question then, if Godard's debut remains such an anomaly, is what does Breathless mean to us in 2008? Naturally, the film is the opening weekend feature of the Godard's 60s series, and it's the spark that's meant to set off the rest of the month's fireworks. It's a deflating cliché to call something "remarkably fresh after all these years," but, yes, Breathless does stand as an exciting and fitting opener: it's so packed with seemingly off-the-cuff moments and little flickers of spontaneity that no matter how many times you've seen it, there's always something you either hadn't noticed or had forgotten was there. Upon this last viewing I was struck and moved when Jean-Paul Belmondo's macho tomfoolery, while waving goodbye to Jean Seberg as she's on her way to that robustly irritating airport interview with Jean-Pierre Melville, is interrupted by an extra exiting a door and walking right into him; Belmondo's little grimace of surprise is the perfect response, and further grants the film the sense that Godard's experiment was to capture those interstitial moments that would never make it into the final cut of other "gangster films." Likewise, there's endless joy in watching Belmondo and, specifically, Seberg, who's constantly reckoning with both her character and her own movie persona—so rudely had she been thrust into the limelight and then cast aside after Saint Joan and Bonjour tristesse that she seems both exhilarated and fearful of the freedom the camera afforded her in Breathless. When she's on-screen, her exquisitely symmetrical features providing necessary contrast to his pugilist's mug, she fitfully becomes the protagonist: she's the one who must make the moral choices, after all.

Breathless was a one-off, but never arbitrary. And unlike those other monolithic, epochal films that changed the face of narrative cinema (Citizen Kane, 2001, Pulp Fiction), Godard's film still feels slippery, and so self-consciously clever that we feel like we may never fully grasp its intentions. It's fun, but never easy, even if it seems like Godard's most accessible. All filmmakers should strive for such simultaneous clarity and obfuscation. So maybe that's why we should still care about Breathless—not as a designated Classic, preserved in amber and placed on the shelf, but as a call to arms for filmmakers, not to repeat what they've seen but to use current technologies to reject narrative formulas and properly confound audiences and themselves. There will be plenty of more visually mesmerizing or intellectually stimulating films on display this month during the Godard's 60s series, but none of them as sprung from youthful zeal to overturn the status quo. —Michael Koresky

Pierrot le fou

Pierrot le fou (1965) is, unignorably, one of Jean-Luc Godard’s goofiest movies. Just as Jean-Paul Belmondo’s character’s name freely alternates between his real one, Ferdinand, and that of the film’s titular symbol of anarchy, Pierrot—the latter chosen by Anna Karina’s betraying lover Marianne, only to be repeatedly rejected by its intended recipient—so does the film freely bounce among subject matter serious and silly until the two are virtually indistinguishable. At its extremes Pierrot le fou offers some of the most gratuitous and wacky indulgences of Godard’s entire career: low-production musical numbers in half-finished apartments and shaded forests, mustachioed dwarfs squawking gibberish into walkie talkies, Belmondo eating an enormous cheese, a cameo by the exiled princess of Lebanon, a netted booby trap capturing a gangster-driven car, etc., etc. These are the logical results of the brand of free cinema Godard has always simultaneously preached and practiced (“One Should Put Everything Into a Film” declared his title to a short published statement, and, man, he sure put his money where he his mouth was), the movie equivalent of the notebook scribbles from Ferdinand/Pierrot’s journal that offer fragments, in-jokes, references, diversions, and off the cuff ideas alongside quintessential set-pieces.

But it’s Godard’s counterbalance of melancholic longing (Rimbaud, Céline, Renoir, the shimmering infinity of the natural world, "the sea gone with the sun") with cartoonish whimsy (the Nickel-Footed Gang, pulp fiction comic inserts, the Mondrian primaries of JLG's pop art-inspired color palette) that makes Pierrot so uniquely and indescribably haunting. This alchemy comes through in the fatalistic gloom pervading the couple’s carefree, liberating flight from the shackles of Ferdiand/Pierrot’s bourgeois respectability into crime thriller intrigue and then Mediterranean coastline refuge (and then back again in an almost completely incomprehensible plot), as in the magnificent scene—one of the most beautiful in the history of cinema, I’ll be so bold as to say—of the two lovers renewing their love in the darkness while a passing stream of multicolored lights reflects off their car windshield, or when Ferdinand/Pierrot dolefully, unforgettably stares back at Marianne during a break in the wishy-washy ode she sings to him after they’ve completed their break with the outside world. Even in the film’s nihilistic conclusion hi-jinks (Marianne and Ferdinand/Pierrot are, after all, low-rent actors, hustling money by telling fanciful stories to café patrons and performing aggressive dumb shows of the Vietnam War for American tourists) mix with death—Ferdinand/Pierrot, ambivalent to the end, clumsily fails to stamp out the lit wick of the two rolls of dynamite strapped to his blue-painted head.

So many of Godard’s heroes and heroines die tragically, but with Ferdinand/Pierrot’s demise comes the poignant sense that something had come to an end at this stage of Godard’s career. Pierrot is a culmination in the sense that it references all his previous movies, but he was still a relative ways away—three years, five films—from entering his militant Maoist phase, while the “playful” strain of his sensibility would always be evident even when severely muted. Yet things would never be quite the same after Pierrot. Godard dubbed Marianne and Ferdinand/Pierrot “the last romantic couple”; Pierrot would be Godard’s last romantic movie. Its follow-up, Masculin féminin, includes these immortal words: “We’d often go to the movies. We’d shiver as the screen lit up. But more often, Madeline and I would be disappointed . . . . It wasn’t the film we had dreamed, the film we all carried in our hearts, the film we wanted to make . . . and secretly wanted to live.” This was Godard’s first admittance of disillusion with cinema, his holy shrine. No coincidence, then, that in Pierrot—where cinema was still, to quote Samuel Fuller’s drop-by monologue, “a battleground”—love goeth before the Fall.

“You speak to me in words, and I look at you with feelings,” Marianne explains to Ferdinand/Pierrot of their communication breakdown. Godard’s rift between the genders is patently personal and just the slightest bit sexist (men think abstractly, read literature, are content in nature; women want sensations, listen to pop music, dream of cities like Las Vegas and Monte Carlo), but the search for an existential purpose amidst the ruins of romance—Pierrot is often cited as an autobiographical rendering of Godard and Karina’s break-up—assumes greater significance. Fittingly, Godard goes all the way back to Jean Seberg for advice, Belmondo watching her across time through the transportation device that is the movie theater: “We were looking carefully for the moment when we had abandoned the fictional character to return to the real one, if it ever existed,” she says on the screen within the screen, camera in hand. If Pierrot is Godard's most frayed dividing line between cinema and real life it’s because the film becomes real life in the daring exhortation to its audience—through the delirious enactment of Ferdinand/Pierrot’s frenzy to be—that there isn’t any difference. It’s making cinema to live to make cinema to live . . . the way out of the maze is only provided by a way deeper into it. If such a strategy didn’t salvage romance for Godard, and if cinema itself would be the next to prove disloyal to his demands on truth and beauty, then it surely rescues life, allowing it to be truly free, in gravitas and goof. And that’s where we should begin in answering Pierrot’s call, by way of Rimabud, that “Love"—and, therefore, cinema—"must be reinvented.” —Michael Joshua Rowin

A Woman Is a Woman

Though it was simultaneously his first color and first 'scope film, Godard's elegantly anarchic A Woman Is a Woman is one of the French New Wave's true anti-spectacles. Beginning with its filmmaker's soon-to-be trademark huge, multicolored, screen-encompassing font emblazoning "Once upon a time," Godard's self-proclaimed musical-comedy is not a fairy tale, nor is it a musical per se, or really much of a comedy, for that matter. It barely even fulfills the expectations of the "love triangle" plot it seems to be advancing. Like the curious tots soliciting Jean-Claude Brialy's help at his book and magazine stand, who refuse his recommendation of Sleeping Beauty in favor of "something sexier," Godard doesn't want to fall into easy generic patterns; in fact, he wants to make sure the audience doesn't either. Always demanding active participation from his audience, Godard plays off his contemporary audience's knowledge of musical-comedies, constantly pulling the rug out by heightening the artifice: bursts of Mancini-esque jazz blare, like they're attacking the characters, then drop out before the moment of catharsis; Eastmancolor primaries saturate our heroine, but then Godard reverses the shot and shows us an actual rotating filter at work; actors constantly break the fourth wall and address the camera directly. They're the sorts of tricks that Godard would apply in different fashion so much over the coming decade that it can only be a tribute to his astonishing gift for subversion that nearly every visual and aural trick in A Woman Is a Woman still shocks to this day.

Watching this gorgeous 1961 oddity again I couldn't help but keep wondering whether audiences—even art-house or festival audiences—would completely reject it had it been made today (not that it was exactly a Breathless-sized hit at the time). It has that unique mix of whimsical and assaultive that Godard was on his way to perfecting (probably by Pierrot le fou, four years later), and a self-referentiality that borders on the oppressive; at any moment the film's never less than completely captivating and purposely alienating, and it's hard to imagine today such militantly New Wave tendencies going down easy (the deliberate pacing of our current moment's "difficult" cinema seems more indebted to Antonioni; no one really much dares adopt Godard's technique).

Of course, the terrific trick of A Woman Is a Woman is that despite Godard's incessant, playful foregrounding of cinema and his total deconstruction of the spaces the characters inhabit (from apartment to nightclub, the former a cluttered romper-room mockery of domesticity, the latter a black void), these are very real people with very real problems. Or, rather, this is a woman with very real yearnings. The film is a gloriously faux-glossy love letter to Anna Karina, who had just starred in Godard's controversial commentary on the Algerian war, Le petit soldat, and who, during this film's shoot would become pregnant (she later miscarried). It's a poignant turn of events, since Karina's character, Angela, a stripteaser at a smoky Parisian club, desires to have a baby, yet is rebuffed by Brialy's live-in lover Emil, finally turning to Jean-Paul Belmondo (as "Lubitsch") to give her what she wants. Bathing Karina in reds and blues, outfitting her in sailor suits and pompoms and sensual scarlet sweaters, Godard makes Karina the ultimate object of desire, while simultaneously refusing to allow us to objectify her.

Watching A Woman Is a Woman is indeed a joyful experience—when Karina exclaims that she'd rather be in a musical spectacular with Cyd Charisse and Gene Kelly, with choreography by Bob Fosse, while kicking her legs up in spasmodic hope, there's no conceivable response but a smile—but the jarring dissociation Godard creates between sound and image (not just the alleged songs but the soundtrack itself, including street noise or incidental score, drops out at regular intervals) constantly problematizes that joy. Karina's Angela is sensible, yet constricted, and despite the ridiculous finality of the title, she is not all she seems. (Neither for that matter is the seemingly priggish but ultimately sensitive Emil, and underappreciated New Wave icon Brialy invests him with just enough sexiness to offset his bookworm mannerisms.) It wouldn't be the last time Karina would play an image of a woman at odds with the woman herself. —MK

Les Carabiniers

A major contradiction of Jean-Luc Godard’s 60s films is that for all their difficulty, abrasiveness, unconventionality, and “distance,” they are largely pleasurable works. We routinely speak of Godard’s subversive tendency, but until he went full-on Maoist and created the militant cinematic Dziga Vertov group with Jean-Pierre Gorin, even his most out-there films—including Marxism media primer Le Gai savoir and One Plus One, a Rolling Stones studio session interrupted by revolutionary vignettes (both from 1968)—contain some kind of sexy fun by way of either radical chic or the near constant “playful” reinvention of cinema, even when in the form of a visual or narrative assault on the audience, and even when Anna Karina isn’t on screen. Just look at the commercial recuperation of anti-commercial Weekend (67), a film in which Godard went far out of his way to completely alienate his audience. Somehow rotten bourgeois protagonists, a reel-long single take traffic jam of blaring horns and mangled corpses, and a cannibalistic denouement weren’t enough, because if you hated it you were just as square as the film’s irredeemable anti-heroes. The film gained immediate supporters and is a “classic” to this day, an irony so ironic that I need go no further in explaining it.

Though it doesn’t mean his other films are compromises or failures (certainly not!), only two or three of Godard’s 60s films escape this trap; among them perhaps the most significant and ripe for reevaluation is Les Carabiniers (1963). Universally trashed by critics and audiences alike upon its release, Les Carabiniers still hasn’t been successfully rescued or rediscovered in recent years. What caused it to be so rejected then and forgotten now? For starters, the film is true to itself. Its subject is the ugly, violent, and wastefully stupid collective “mobilization” known as war, and the film enacts—relentlessly, absurdly, bitterly—that ugliness, that violence, that wasteful stupidity. Unlike virtually every other war movie, even every anti-war movie, Les Carabiniers refuses to pull punches by offering courageous heroism, thrilling action, or manipulative emotionality to offset war’s suffering and horror. This is not because the film is particularly violent or graphic, but because everything about it is off-putting, from its characters, two troglodytic dolts named Michel-Ange and Ulysse (Patrice Moullet and Marino Masé), forced to go to battle by order of the King, and their shallow, materialistic wives Venus and Cleopatre (Genevieve Galea and Catherine Ribeiro); to the unceasing parade of cowardly, graceless skirmishes that often end in systematic slaughter or disgusting, juvenile violation (nearly all the women in the film have their skirts lifted up by soldiers with their guns); to the film’s overall look, over-processed black and white that comes out as a drab, desolate palette of grays, grays, and grays, rendering the barren, wintry landscapes of ruined rural cottages and personality-less apartment complexes all the more drearily depressing.

Les Carabiniers is a satiric fable in the aggressive tradition of Alfred Jarry (Ubu Roi is its obvious point of reference)—following through on its opening Borges quotation, everything in the film has been simplified (but not abstracted) for maximum bluntness. The miserable characters shout at each other in monosyllabic grunts (a typical exchange: “Shit!” “Why?” “Because”), and it’s not a coincidence that the only one who speaks out against the mindlessness of war is also the only one who speaks in Godard’s patented language of complex allusion. Michel-Ange and Ulysse look forward to and then enjoy their military service because of the boundless plunder promised them (“Hawaiian guitars, elephants”), and their unfeeling brutality comes through not only in the atrocities they commit, but in their banal descriptions of the atrocities in their postcards home, which Godard took from actual war-time correspondences: “A lot of blood and corpses . . . We kiss you tenderly.” Godard in turn depicts Michel-Ange and Ulysse’s tragic misadventures as banally as possible. Long takes are employed for demoralizing, drudging marches through forests that end in mass execution—the climax of these marches are as dryly portrayed as the long walks to them. Actual documentary war footage counterpoints Godard’s documentary-style fictional events, and here’s where Les Carabiniers becomes an extremely important moment in the demystification of the war movie, and the movies themselves. Godard accomplishes this by calling attention to the unreality of representations of war, be they documentary or fictional. On the micro level he painstakingly and accurately matches sound effects with their specific sources (“we never had a Heinkel roar for a Spitfire,” he explained in his first and only retort to critics after the film’s disastrous reception), but then cuts these noises in and out of the mix so abruptly and artificially that they can’t help but be noticed as separate images and sounds. Brecht is, as usual, the presiding spirit of Godard’s strategies. The characters are cinematic constructs and not “real” people or soldiers—all unknown actors, Moullet and Masé possess the odd physical exaggerations of a silent era comedy duo (the former a bizarre, freakish bumpkin boy, the latter a cigar-smoking, unshaven lug), while Galea and Ribeiro’s pancaked makeup and overdone lipstick make them ghostly, childlike apparitions straight out of a Griffith two-reeler.

As such, Les Carabiniers’ fable-like characters are images of images. But more than that, their understanding of the world is a misunderstanding of images. Michel-Ange attends his first movie and tears down the screen pawing at the naked woman in a bathtub projected there. Later he and Venus place two-page magazine ads for bras and men’s underwear over their own anatomies. And in what is the film’s most notorious sequence, Michel-Ange and Ulysse unpack a briefcase containing their spoils of war, categorized postcards of monuments, natural wonders, animals, paintings, and women they take to be deeds for the real things. The scene goes on for more than ten minutes, an appropriately exhausting metaphor for the bottomless commodization of life by societies and individuals ready to abstract the world into a collection of conquerable objects. The last commodity, of course, is war itself, which is why Godard refuses to make his film just one more palatable illustration of war. If we think of the world as images, then people are merely images, and therefore disposable; if we think of images as images, and not reality, we set our priorities straight; and, with respect to the influence of images and the reality they pretend, if we make our images bullshit-free maybe we can begin to look at the world they represent without the corrosive illusions that keep us in their potentially infantilizing, desensitizing power. —MJR