Public Space

Imogen Sara Smith on Playtime

“Got a match?” A workman with an unlit cigarette approaches a building guard in a scene near the beginning of Playtime. Wordlessly, the guard gestures the man to move to the left, and the camera pans with them to reveal a door: the two men have been standing on either side of a plate-glass wall, which neither the workman nor we (the audience) had noticed. This small yet perfect gag is in the classical traditional of visual comedy, which mines the countless ways that people—both in a film and in the audience—can be fooled or surprised by an angle of vision. But Playtime, arguably the most ambitious visual comedy ever made, is hardly traditional—and it is certainly not small. Jacques Tati’s 1967 masterpiece goes far beyond satirizing modern architecture and technology to create a strangely elated celebration of the way people move through space.

When asked why he chose to make Playtime in 70mm—the first and only time he used the costly format—Tati responded that it was necessary to capture the scale of modern buildings, since he intended the décor to be the star of the film. Playtime’s 1.85:1 aspect ratio is unusual for 70mm (the wider 2.20:1 or 2.35:1 might be expected) but allows for higher resolution on wider screens. What Tati was after was not merely size but a staggering level of detail that fills every frame, enabling him to simultaneously capture the intimidating scale of International Style buildings and the tiny, comically petty humans who populate them.

To realize his vision, the scale of which left him financially ruined when the film failed to make back its costs, he constructed a whole neighborhood on the outskirts of Paris, known as Tativille. These massive sets are not a backdrop for the comedy; they are the comedy. Glass, the quintessential modern building material, is not just thematically crucial to the film, representing the homogenized, transparent yet impenetrable international city; it also gets many of the biggest laughs. The spectacular, startling effect of a plate-glass door shivering and crumbling into powder is followed by an even funnier moment when a doorman improvises by picking up the doorknob to open and close an imaginary door for oblivious patrons. Throughout the film, glass doors opened at the right angle suddenly afford glowing reflections of the Eiffel Tower or Sacré-Coeur, wistful visions of the past superimposed on the super-modern. These apparitions are topped by a ravishing moment when the tilting of a window-pane causes the reflection of bus passengers to soar up into the air, as though on a carnival ride.

Glass windows create frames within the overall frame of the film, adding to the exquisitely composed tableau vivante quality of Tati’s mise-en-scène. (It seems a touch too perfect that Jacques Tati’s maternal grandfather was a Dutch picture-framer, and that he was expected to enter the family framing business. In a sense he did.) In one of the film’s most elaborate sequences, the glass walls of four adjacent apartments float like screens above a dark street. Inside, people are watching screens we can’t see—televisions cast flickering shadows—and acting in their own unconscious shadowplays, as when a woman in one apartment appears to be gazing intently at a paunchy man in the next apartment as he disrobes. For a long time we watch the people in the windows talking, but hear only the traffic noise of the street. In an earlier sequence, when Monsieur Hulot (Tati, reprising the trademark character he’d played in two previous features) is alone in a glass cube waiting room, we alternately hear the traffic noise of the street and the silence and small sounds inside the room as the camera cuts back and forth across the barrier—a subtle effect that brings the viewer inside the space of the film. Tati cited the sophisticated effects made possible by 6-track sound as the other reason he chose to shoot Playtime in 70mm; he had made use of expressive, magnified sound effects in earlier films, but here he also evokes place and movement with sound that pans.

Playtime is a nearly infinite emporium of spatial gags and visual rhymes. Effects such as arching street lamps that echo the shape of a lily-of-the-valley brooch appear as effortless grace notes, but were in fact the result of grueling labor. Tati put tireless planning and trial and error into figuring out how, for instance, to shoot a waiter pouring champagne so that he would appear to be watering the flowered hats of American tourist ladies. In the worlds of Tati’s films, not a single thing is haphazard; even waves and wind are perfectly timed in his 1953 film Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday. Playtime’s urban sets employed movable building facades papered with photographic images of metal, not only to save money but also to eliminate unplanned reflections. Perhaps the most miraculous thing about the film is that its entirely constructed, artificial world doesn’t feel oppressive or airless.

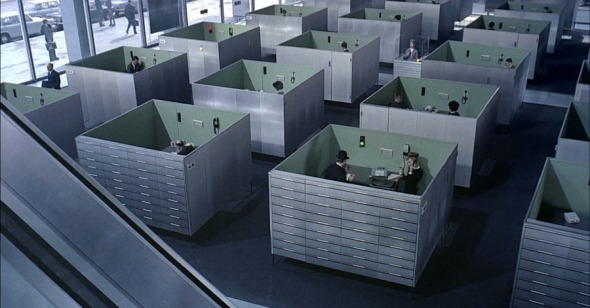

As a performer, Tati has a remarkable knack for appearing aimlessly adrift in the world that, as a director, he obsessively controlled. His Monsieur Hulot is an unusual comic character, consisting of barely more than an outline. Unlike the characters played by Tati’s heroes, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, he has no burning determination to succeed and win the girl. Indeed, he has no particular motivation at all, leading to movies that blithely proceed without plot or defining conflict. In Playtime, Hulot is tasked with delivering some papers to a businessman named Giffard. We never know who sent him, what the papers are, or what Giffard does. The long sequence in which the two men pursue each other fruitlessly around a vast warren of cubicles, elevators, and glass curtain walls turns Kafka into a comic ballet. Hulot is always vaguely befuddled yet amiable and serene. The all-encompassing yet not unpleasant confusion of this opening scene proves to be the film’s dominant mood.

Playtime was the third film featuring Hulot, and while at first glance it neatly completes the trajectory begun by the first two, it actually represents an unexpected turn. Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, the first film, is a nostalgic distillation of the old world, a timeless French summertime preserved in the amber of eternal sunshine: every day like the next, every year like the one before, a human-scaled world of delicately cartoonish miniature dramas—nearly all filmed in medium shots. Mon oncle (1958) starkly contrasts this quirky, impractical, charmingly messy old world with a sterile, pretentious modern world of cold, uncomfortable architecture and absurdly regimented factories; the former personified by the hapless Hulot and the latter by his status-obsessed in-laws. In Playtime, the old world has virtually disappeared, apart from the reflections occasionally glimpsed in glass doors. Yet while the modern world is gently satirized, the caustic comparisons drawn in Mon oncle have vanished into a uniquely tolerant sense of bemused awe: what Jonathan Rosenbaum (in his essay for the Criterion DVD release of Playtime) calls “a particularly euphoric form of reengagement with public space.”

The first two Hulot films were shot in the traditional, nearly square 1.33:1 aspect ratio. The panorama of Playtime’s larger canvas brings a grandeur and expansiveness, very different from the bourgeois fussiness of Mon oncle’s fashion-victim architecture. The rectangular frame also fits the horizontality that is so central to midcentury modernism. Horizontality expresses a vision of the modern world as decentralized, democratic, cut off from vertical roots of locality or tradition, and perpetually in transit. Tati underlines this with slow horizontal camera movements, and fills the wide screen with long diagonals that add depth to the compositions. One of the film’s central jokes is how much space there is: in the cavernous public areas of airports and office buildings people bounce around like electrons on crisscrossing paths. He uses every inch of the screen, often inserting gags in odd corners where they are easily missed, packing the frame with massed crowds whose precisely choreographed movements create an overall impression of autonomous energy. The people onscreen (some figures in the backgrounds are in fact photographic cut-outs) are still meticulous caricatures—every actor and extra is copying a stylized gait and set of mannerisms supplied by Tati himself. (He got his start as a mime with an act where he did impressions of people engaging in different sports, and his approach to character was always through physical mannerisms.) Even the figure of Hulot is multiplied by look-alikes often glimpsed in the background, sly reminders that any one of the circulating figures could be a center of attention.

There are very few close-ups in Playtime, a grand-scale illustration of the truism (attributed to various comedians, including Buster Keaton) that tragedy is a close-up, comedy is a long-shot. The audience has to be sufficiently distanced from a person on screen to be able to laugh when he falls down. Playtime takes this to another level: the distancing of long shots seems to affect the people in the movie too. They are impassive, adrift in that vague, somehow pleasurable confusion that is the film’s reigning mood. They are—pun intended—“spacey.” This effect is most apparent in the long nightclub opening-night sequence in the film’s second half. A formal and pompous event that goes dreadfully awry and spirals into chaos, this set piece is both solidly in the tradition of slapstick comedy and a radical departure from that tradition. The difference is that in, say, a Laurel and Hardy film, the nightclub patrons would be apoplectic, the management would be hysterical, the hapless staff would be black and blue, and food would be flying. In Playtime, though there is a low and constant level of agitation, everyone ultimately just goes with the flow, and what starts as a disaster turns into a really great party, since no one seems to care whether they get anything to eat, or their clothes get ruined, or the ceiling caves in. Tati goes even further in the sublime conclusion to the film, turning a traffic jam—one of the worst aggravations of modern life—into a surreal, beatific carousel.

This oddly serene, detached emotional tone emanates from the movie’s sets and the stately way they are framed; it is as though these surroundings make it impossible for people to express rage. This is certainly the case with the one person who does lose his temper, the German proprietor of an Expo booth selling noiseless doors. Exasperated by a case of mistaken identity, he flies into a Teutonic tirade of sarcasm, then crowns it by banging shut one of his own doors—with a hilariously anticlimactic lack of sound. (The slogan of his booth is, “Slam your doors in golden silence.”)

Even more crucially, perhaps, the world of Playtime has absolutely no interiority. There is only public space. Every room has glass walls; every person is a unit of the crowd, no one expresses a private thought or inner feeling. This quality too seems related to the widescreen format, which—despite directors such as Nicholas Ray who proved it can encompass an intimate, interior style—has more often been seen as appropriate for spectacles; or, as Fritz Lang famously says of CinemaScope in Contempt (1963), fit only for snakes and funerals. Jacques Tati found a way to use the potentially alienating scale afforded by 70mm to express his artistic vision, which is perhaps most perfectly summed up in his final film, Parade. (Though it was made for the small screen in 1.37:1, commissioned for Swedish television in 1974.) A staged circus performance that focuses nearly as much on the audience as the performers, Parade brims with Tati’s warm affection for people and his view of them all as performers, whether conscious or not.

This warmth also suffuses Playtime, beneath its cool glassy exterior. It is a film about strangers, people connected only by sharing the same space, that begins with suggestions of alienation (people divided by glass walls, dining alone in the eerie green glow of neon-lit drugstores) and builds to a transcendent vision of communal harmony: the spontaneous party in the nightclub, Hulot’s impulsive gift of a scarf and pin to a pretty American tourist as she leaves for the airport. No lasting relationships are formed; everyone remains in transit, moving together and apart, calmly uninvolved. Here, as in Parade, Tati implies that spectacle is how we fundamentally experience the world, both as actors and observers. The movie screen is an idealized public space on which Tati’s people, framed in all their foolish glory, demonstrate the joys of being one-dimensional.

Playtime played Friday, March 6, 2015 at the Museum of the Moving Image as part of See it Big! High and Wide, a series co-programmed by Reverse Shot and Museum of the Moving Image.