The twenty best films of the decade were determined by polling all the major and continuing contributors to Reverse Shot in the publication's history.

Breaking and Entering

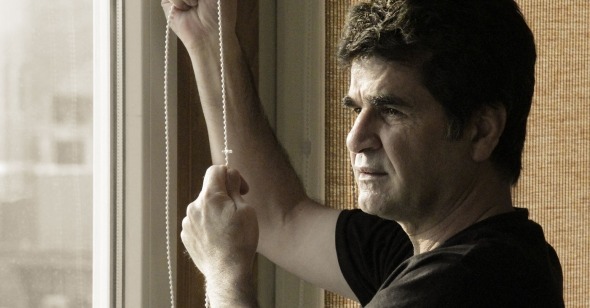

Ela Bittencourt on This Is Not a Film

I am writing about Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film (2011) while in Brazil. Viewed from this vantage point, Panahi’s “non-film”—an “effort,” as Panahi brands it in the credits, co-helmed with the Iranian filmmaker Mojtaba Mirtahmasb—is a perfect, one might say, logical response to the spreading non-freedom of expression. This threat to freedom is felt in Brazil, where, though directors aren’t literally banned from working, there is fear, and also news and rumors of censored projects (most recently those with LGBT themes). But more than an exercise in how to evade censorship, This Is Not a Film is also a film essay, of sorts. It interrogates the essence of cinema, and poignantly shows how a film experience transcends its purely technical means.

To briefly outline its premise: Panahi is confined to his apartment in Tehran, when the Iranian director Mirtahmasb visits him on New Year’s Eve. Panahi has asked Mirtahmasb to help out—his last film failed to get approval and couldn’t be made, so he wants to reenact a few of its scenes inside his apartment. Mirtahmasb is to capture these scenes on camera. In fact, Panahi captures a bit of footage even before Mirtahmasb’s arrival, to establish the domestic setting. The early scene, with his family’s voices on the soundtrack, as they record their messages on the answering machine in his bedroom, conveys his claustrophobia and isolation. The entire action—with the exception of one scene at the end—takes place inside the apartment. In the course of filming, Panahi will read out loud bits of dialogue from his unrealized script. But there is more to this circumstance: Panahi was at this time awaiting a verdict from an appeals court. He has been censored, forbidden to make movies, and should expect—as informed by his lawyer, who calls in during the filming, their conversation also captured on camera—to be sentenced to twenty years without work, and to some years, possibly a decade, in jail (luckily for Panahi, the sentence was later reduced, and he has directed four films since, despite an official filmmaking ban).

What’s inspiring and audacious about Panahi’s reaction to his silencing by the courts and his attempt to resurrect his unmade film—and create a new “non-film” while doing it—is that he treats his situation like a logistical and philosophical puzzle. Ironically, but also a bit comically, the first conversation he has with Mirtahmasb in preparation for their “non-filming” is cinematic. “Right now the problem is over-exposure,” Mirtahmasb notes. “Too much light.” Beyond a technical solution—they move to another room—Panahi finds an ingeniously demagogical answer to the governmental demagogy that forced him into creative paralysis. “Now that I’m not allowed to make a film, perhaps by reading and explaining, I might create an image of it,” he says. Thus Panahi resorts to the idea of non-materiality—as long as the image he creates is only in our heads, he can claim that what he has presented us with is not the thing itself: it’s a non-film.

But can we truly picture it in our mind’s eye? Panahi goes diligently about re-creating a few scenes for us in his living room. Mirtahmasb is the perfect man to assist him: he says he wanted to make a film of his own, a documentary, “Behind the scenes of Iranian filmmakers not making films”—and this is, essentially, slyly, the very film that Panahi and Mirtahmasb make. (We can imagine how this would play out in court, had the footage been apprehended and examined—lawyers on opposite sides arguing film vs. non-film.) Meanwhile the craft is all in Panahi’s mind, even if we don’t entirely buy into the idea that he has Mirtahmasb helm the camera because he himself doesn’t know about technical stuff. Panahi quickly outlines an imaginary perimeter with white tape, and then describes how the young heroine of his unrealized film sits in her small room, yearning to escape to the university and to study art, against her conservative family’s wishes. (Not one to easily let go of an idea, Panahi did finally make a fiction feature, 3 Faces, in 2018, based on a nearly identical premise—this time with a teenage girl in the countryside, who resorts to drastic measures when forbidden by her parents to study acting at a conservatory). Though their social circumstances differ, we can nevertheless sense Panahi’s identification with his protagonist’s confinement.

At one point, Panahi pulls out his phone, and shows us a documentation clip for his unrealized project. We are suddenly transported—a non-film has another non-film buried inside it, like a perfect gem. The documentation is of the house in which the original film was going to be shot. And we can sense that this house’s walls, rooms, smells, still percolate in Panahi’s imagination. This transposition—prototype and reincarnation—is the magic of cinema.

By the end of his restaging, however, Panahi appears deflated. “If we could tell a film, then why make a film?” He has reached the limit of what he can do, even with the help of visual clues. And yet, he has created a potent image—of a filmmaker desperate to make films. This Is Not a Film is thus a bittersweet game of subterfuge, of smuggling in images, a film masquerading as a non-film.

This game provides welcome distractions, as Mirtahmasb records Panahi’s and his own banter. “This is an activity related to cinema,” Mirtahmasb warns in one instant. “What is?” Panahi asks seated on the sofa, while Mirtahmasb watches him watching the news—a banal activity, so “uncinematic,” we might say. “This film being made,” Mirtahmasb presses further. “You call this a film?” Panahi scoffs. Mirtahmasb responds, “Beats me.” It’s a sport between these two, though at times it turns disconcerting: “Take a shot of me in case I’m arrested,” Mirtahmasb laughs, “there will be some images left.”

This Is Not a Film wouldn’t be as gripping had it remained a purely semantic camouflage. But Panahi also touches on form: what does it mean to direct a film? To illustrate, he replays on his television set scenes from his previous films, shot with nonprofessional actors. In one, a young man, Hossein, is humiliated in a jewelry shop, and as he comes out, he leans against a wall appearing faint. Panahi pauses the image, a remote in his hand. The professional actor, he seems to suggest, would have followed the script more closely. Instead, the amateur actor did an uncanny facial expression, rolling his eyes back in their sockets, and then pulling down his wool hat over them. The effect leaves Panahi transfixed. “He does the directing on you. He leads you to how you explain the film,” he summarizes the scene. In another clip, a young woman in an abaya rushes through a portico of a government building. “Here the location is doing the directing,” Panahi states categorically. What he means is that the vertical lines of the building’s pillars, beyond creating a visual rhythm, also express the woman’s anxiety, as her abaya flutters through the space.

Is Panahi questioning the way industry, and in this case, Iran’s courts, insist on the director’s sole authorship? More likely, he’s pointing to the fact that, while working in isolation, he is bound to fail—cinema is more than the authoring mind; it is earthbound, communal, and location-specific. And yet we can’t help but note that in an earlier scene, in his bedroom, he did use cinematic means—the empty frame, the loving voices, close yet distant on his answering machine—to create a similar effect of spatial and temporal echo.

Panahi is perhaps also being ironic, since he’s ostensibly only acting in This Is Not a Film, yet we know it’s his project. More profoundly though, his observations hint at an aesthetic manifesto: film is magic, serendipity; it is image more than word, spontaneous gesture as much as careful staging. It’s that extra quality—of life—that matters.

Similarly to Martin Scorsese, Panahi has strict ideas about the quality of the cinematic image and the proper means to render it. However, he doesn’t want to disrupt the flow of filming, so as Mirtahmasb prepares to leave him, and in a moment of desperation, he reaches for an iPhone. Clearly alluding to the political situation and atmosphere in the streets, Mirtahmasb suggests that had Panahi turned on his iPhone camera earlier, after leaving prison, he could have recorded many important things. Panahi has recorded some—during the filming, a friend has called in to say that the police saw his camera, but he was let go, their conversation on a speaker.

A phone camera then, as an antidote to fear, lies, silencing? Panahi objects to the poor quality of the gadgets’ imaging. But when the building’s substitute caretaker arrives to take out the garbage, Panahi takes the elevator down with him to the street level, as if prompted by Mirtahmasb’s words. Here’s his chance to capture the unvarnished truth—even though the young man quickly catches on, and starts to fix his shirt. Nothing in this scene seems random: the young garbage collector is doing his family a favor; he’s really an art student. He recalls how, one day, secret police had barged into his family’s apartment. We then come across the reality that Panahi’s friend might have had in mind. But Panahi isn’t interested in ferreting that reality out. Instead, he returns to the subject of the young man’s studies. The iPhone keeps rolling; the two men speak of getting away from the city. The bitterness of an art scholar’s—an artist’s—fate isn’t lost on western viewers. “You graduate with a master’s degree and then there’s no job for you,” the student quips, as he wheels out the trash.

What might have been a raw instant of vérité, in Panahi’s treatment becomes a metaphor for his predicament.

And then they’re in the street. Fireworks crack overhead, fires glow. There’s excitement and fresh air, after a prolonged isolation. Isn’t this the liberation that technology has promised?

“Mr. Panahi, please don’t come outside,” the young man warns. “They’ll see you with the camera.”

So much for breaking out or the omnipresence of phone cameras, though they have recorded scenes of unrest worldwide, which may not have been captured with more visible equipment. In Panahi’s film, however, there is no such redemptive reveal. The gate merely closes; the young man disappears into the dark. This Is Not a Film’s non-credits roll—“Special Thanks,” followed by dots instead of actual names.

Appropriately, we are left with non-closure, but the experience itself has validated the process. Early in This Is Not a Film, Panahi spoke of the child actress, Mina Mohammad Khani (Mina), in his second feature, The Mirror (1997). He played a clip of an almost “non-film”—the scene in which Mina gets annoyed, because she’s on a bus that’s going in the wrong direction, and suddenly breaks the fourth wall. She knows how to get home, she says, but for the sake of Panahi’s fiction has been forced to pretend she doesn’t. And so she calls it quits, makes the cameramen stop, peels off the fake cast from her arm and gets off the bus. Panahi, as seen in the sequence, decides to make the most of Mina’s rebellion, and follows her with his cameraman. What in another film would have been a discarded outtake instead lends Panahi’s narrative a delicious twist.

“I’m in a similar position as Mina,” he now says, reflecting on his confinement. “Somehow I must remove my cast and throw it away.”

Panahi then adopts the obstinate wisdom of a child, her will to challenge the rules of make-believe and affirm the real, which is ardently, defiantly hers. The lie that he must test and lay bare is no less than his rigid preconception of what constitutes cinema, pitted against his desire for work, with any means left. In this context, to resist one must create. Panahi’s non-film may be modest, faulty, or poor—an “effort”—but this doesn’t preclude it from speaking his truth.