Man Without a Movie Camera

by Chris Wisniewski

This Is Not a Film

Dir. Jafar Panahi, Iran, Palisades Tartan

Jafar Panahi is in danger of being reduced to a cause. Arrested in 2010 on nebulous charges that he was engaged in making a propaganda film attacking the Iranian government, Panahi was sentenced to six years in prison and received a 20-year ban from directing or writing any new movies. Panahi’s arrest galvanized the international film community, eliciting petitions and symbolic acts of protest (Panahi was made an honorary member of the 2010 Cannes jury, and an empty chair was reserved for him at the festival). Lost in all of this advocacy, however, are Panahi’s movies themselves. If he deserves to be called one of the world’s great filmmakers—and he surely does—it is on the basis of his extraordinary oeuvre, not because of the oppressive actions of an autocratic regime.

For Panahi, though, filmmaking has always had a political dimension. From his debut feature, The White Balloon, through 2006’s Offside, Panahi has explored contemporary urban life in Iran through intelligent and humanistic narratives that touch, ever so delicately, on issues of class and gender. Never a didactic or polemical filmmaker, Panahi puts character and story first, thus allowing the political realities that structure his characters’ lives to reveal themselves slowly, lending an authenticity that a more direct approach might compromise. To lose a filmmaker of this caliber at the peak of his career is a staggering blow for world cinema. All of which is to say that This Is Not a Film—which Panahi made while under house arrest awaiting sentencing, collaborating with his friend, the documentarian Motjaba Mirtahmasb—is more than a great, devastating piece of moviemaking; the movie (smuggled to the 2011 Cannes Film Festival on a USB drive inside of a cake) is something of a cinematic miracle.

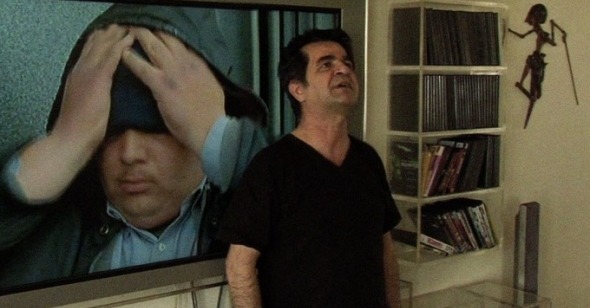

Shot on Panahi’s personal camcorder and iPhone and clocking in at a brisk 70 minutes, This Is Not a Film at first seems defiantly nonmonumental. It opens with a static shot of Panahi’s kitchen table, where the filmmaker eventually sits and eats a breakfast of bread, jams, and spreads while he tinkers on his phone and calls Mirtahmasb. Panahi goes to the bathroom, phones his lawyer, feeds his daughter’s pet iguana, and wanders around his house. Eventually, a somewhat bemused and exasperated Panahi dispenses with the illusion and looks directly into the camera, declaring his desire to “throw the cast off.” It’s a clever nod to the pivotal moment in his 1997 film The Mirror when his young female protagonist breaks character, shattering the fiction onscreen and sending that movie in an entirely new direction. Unlike The Mirror’s little Mina, who makes her comments to the offscreen cast and crew, Panahi addresses the audience of This Is Not a Film directly. Then he cuts to the relevant scene from The Mirror, in which we see a much younger Panahi react to the girl, following her with his camera as she leaves the shooting location. As the scene ends, we discover that we are actually watching the movie with Panahi on his television; the camera pulls away from the screen to reveal him staring intently. The gesture is brilliantly meta—we watch Panahi watching Panahi following the girl who had been playing one character but is now playing another. Films within films within films. With the camera movement, This Is Not a Film also first acknowledges Mirtahmasb’s presence. For most of the film’s running time, he stays behind the camera to be its principal operator since Panahi refuses to shoot footage himself, to avoid violating the letter—if not the spirit—of the ban.

What first seems like a day in the life of a filmmaker under house arrest thus slowly reveals itself to be something more complex. The reference to The Mirror is the first of multiple instances in which Panahi uses his own films—including one as yet unmade—to reflect on his circumstances and on the art of moviemaking. Shortly after “throwing the cast off,” Panahi asks Mirtahmasb to shoot him as he “creates an image” of the screenplay he wrote prior to the ban. The artistically muzzled director, unable to make the movie himself, instead describes its plot, shows images of the actress he hoped to cast as a lead, uses an oriental rug and some masking tape as a makeshift set, and explains in great detail the first shot and sequence. He and Mirtahmasb joke that this exercise is a kind of “behind the scenes of Iranian filmmakers not making films,” but it’s also an exhilarating look at a filmmaker’s planning process, at what inspires him and how he translates that inspiration into a visual and narrative system. The sequence is simultaneously imbued with a vigor derived from Panahi’s passion for his craft and a sadness born of the realization that the movie he is “creating an image of” will likely never exist.

The plot of the screenplay centers on a young woman who is locked in her house by her conservative parents—an uncanny parallel to Panahi’s house arrest. This is the first indication that This Is Not a Film may (or may not) be more carefully conceived and planned than its makers first let on. Had Panahi really finished the screenplay prior to his arrest, or has he concocted the story as a metaphor for his own predicament? This movie may in fact be the pinnacle and a microcosm of the contemporary Iranian art cinema that Panahi helped to define and usher onto the world stage: a metacinematic exercise with a human heart, it deftly blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction utilizing amateur actors who only happen to be the filmmakers themselves. One might have reason to suspect all of the footage was shot on the same day—periodic bursts of fireworks are heard from offscreen, it being the first ever “Firework Wednesday,” a day of protest against the government (Panahi used soccer games in similar fashion in both The Mirror and Offside to establish and validate his timeline)—but even this is a sleight of hand that masks a purported four-day shoot.

Panahi eventually gives up on his attempt to walk his audience through his screenplay. Commenting on scenes from other films in his oeuvre, he explains with penetrating artistic insight that movies are, in effect, sui generis, the products of a process that inevitably shapes the result. Without actors, locations, sets, and cameras it is impossible for Panahi to make his movie—there can be no movie—and yet he continues to feel the irrepressible urge to direct. This Is Not a Film illuminates this contradiction in heartbreaking fashion. Panahi seems completely engaged as a filmmaker, thrillingly alive to the possibilities of the medium, and yet he has been silenced.

In this sense, the title of this movie is pointed. However startling, moving, or engrossing this 70-minute project might be, it is, finally, not a Jafar Panahi film. So what is it, then? A tribute. A call to action. A protest. A wail.

Fittingly, Panahi and Mirtahmasb dedicate it to Iranian filmmakers. Their government has turned against one of its most vital artistic communities. As depressing as that fact is, it is also a reminder of exactly how much cinema still matters. In the months since This Is Not a Film was made, Mirtahmasb, too, was arrested, another voice of resistance denied the right to speak. This Is Not a Film concludes with an admonition. As he walks out of his home, Panahi is reminded to remain indoors, to not risk being seen outside with a camera. It is a sobering reality check. But if this heroic work has a decisive message for its viewers, it comes slightly earlier, in an instruction Mirtahmasb gives to his courageous friend: “It is important that the camera stays on.”