In the beginning, there was the Steven Spielberg Issue. It was Reverse Shot’s first true “issue” to be based around our symposium format, way back in early 2003, and it raised an ongoing cinematic issue as well: the debate over Spielberg as artist.

When considering Spielberg, something like the sensitive Hercules of American filmmakers, we were, at that time, still high off the fumes of Minority Report, Catch Me If You Can, and, most importantly, A.I. Artificial Intelligence; the latter was such a rallying point for the founders of the magazine that without it Reverse Shot may never have existed at all. However, considering the skimpy amount of writers we had at that time, we were not able to do full justice to this ever-divisive, most successful Hollywood director of all time. Since then we’ve given complete career treatments to Brian De Palma, Claire Denis, Gus Van Sant, Hou Hsiao-hsien, and more. We had always planned on going back and doing it correctly, and now, following two impressive, if, as always, debated, back-to-back films—War Horse and The Adventures of Tintin, both nostalgia-drenched throwbacks, even if the latter was motion-capture animation—the time seemed ripe.

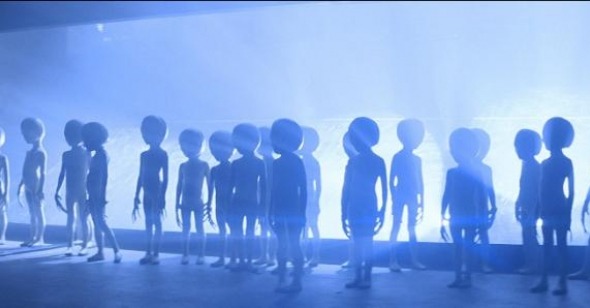

Fascination with Spielberg is usually generational. Many of our writers fall in that Spielbergian sweet spot: we were raised on E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Poltergeist, rewatching videotapes of these films until they were worn out, growing so accustomed to their mechanics that they became The Movies themselves, at least until we discovered what else was out there. They were so close to us that it became difficult to criticize them at all, even later in life, when we were expected to “know better.”

As we grew up, the story went, so did Spielberg. For some, he got too big for his britches, making serious “adult” films that dealt with race, the Holocaust, World War II. He even dared to adapt and emulate the holy Kubrick and make a film about Israel-Palestine. At this point, it should be clear that Spielberg cannot be pigeonholed or underestimated, and that his identity as a filmmaker is as bound to films like The Color Purple, Schindler’s List, Amistad, and Munich as much as Close Encounters, E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark, and War of the Worlds.

Doing right by Spielberg in the Reverse Shot tradition doesn’t mean hagiography. A series of reaffirmations of Spielberg’s genius would be just as reductive and dull as endless essays on his alleged conservatism, and his “limited” focus on childhood and the family. The plurality of voices that Reverse Shot has become now affords us the opportunity, nearly a decade on, to really look at what makes this mega-mogul-cum-auteur (a true rarity) tick. In these pages you’ll find detractors mingling with boosters, those who believe his filmmaking is a tyranny as much as a blessing.

In 2003 we wrote, “Spielberg is coming off a two-year golden streak that has heightened the inherent schism in his career: Minority Report (dystopic roller-coaster ride or serious political inquiry?), Catch Me If You Can (flippant nostalgic breeze or melancholy rumination on withering patriarchy?), and, most dramatically, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, have all pushed the director (who publicly disavows auteurism itself, preferring to think of film as a collaborative medium) into even more contentious realms of audience response.” The divisive response to his films hasn’t changed much over the years, especially to his stunningly dark 2005 twofer of War of the Worlds and Munich.

In 2012 we think the best we can do for Spielberg is simply look at his career, from the beginning to the end: perhaps in this progression is the key to who this artist is and what he’s wrought. Cycling from television to action blockbusters to human dramas to historical epics and back again, Spielberg has been something of a journeyman whose transformative effect on cinema has been gradual but definitive. He makes us cry, even if we don't always trust our tears, and makes our jaws drop even if we feel toyed with. There’s truth even in his most fanciful moments, and fanciful moments even in his most seemingly sober works. There’s history in his goofy action adventures, and goofiness in his history. Love him, hate him, or begrudgingly admire him, there is no American filmmaker who so decisively changed the landscape of moviemaking.