Life Cut Short

Esther Rosenfield on P.T. and Metal Gear Solid V: Phantom Pain

What does it mean for a game to be complete? It’s routine for a game to be released in an unfinished state, with the expectation of patches and downloadable content that will later complete the work. Even before games could be updated live via the internet, it was part of the nature of the medium that games existed in a half-formed state, with optional post-hoc expansion packs. A film director may tinker with their work later, recutting scenes or futzing with color correction. Game creators have the potential to create whole new scenes after release and graft them onto the original cut.

In the mid-2010s, Hideo Kojima created two video games: P.T. (2014) and Metal Gear Solid V (2015). Both of them were released incomplete as a result of his crumbling relationship with Konami. Yet they are nevertheless landmark works whose influence is still felt a decade later. Neither is a finished game, but they are so rich as to feel whole. If video games are inherently incomplete, these are apt case studies through which to explore this strange contradiction.

In 2014, Kojima seemed stuck. He had tried multiple times to release a “final” Metal Gear Solid game only to find himself at work on a new entry, and the expectations associated with the franchise weighed heavily on him. Much like Stephen King when writing as Richard Bachman, Kojima wanted to release a game without players’ experience being clouded by the presumptions associated with his name. With P.T., he gave it a shot.

At the time, Kojima (along with his friend Guillermo del Toro) was secretly in preproduction on a new game in the Silent Hill franchise, a beloved series whose latest entries had lacked the artistic vision that made the original games so critically acclaimed. In order to tease the project, which could not begin full-scale production until after Metal Gear Solid V was complete, Kojima and his team created a “playable teaser” for the game, prospectively titled Silent Hills. When P.T. was announced, it was credited as the creation of a group called “7780s Studios,” and Kojima’s name was nowhere to be found in its marketing. Players would experience P.T. without the burden of expectations.

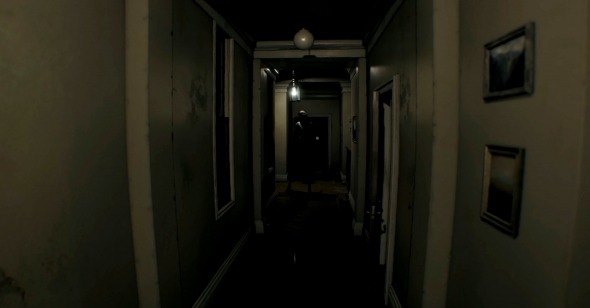

In simplest terms, P.T. is a horror game in which a player must solve enigmatic puzzles in order to escape iterations of a looping hallway before they are killed by a vengeful ghost named Lisa. The L-shaped hallway bends to the right and leads to a downwards flight of stairs, at the end of which a door leads right back to its beginning. There is a bathroom which is sometimes locked. There is a second-floor landing, visible but not accessible. There is a table with a phone and a table with a radio. These are the consistent elements; everything else is subject to change as the player progresses.

The game’s lack of direction creates a feeling of desperate isolation. The game won’t tell you what to do, and you are trapped in the hallway until you can figure it out. Kojima intended the game to take weeks to be solved for the first time (its final puzzle solution requires collaboration, as not all players have access to every clue; it was first solved on a live stream entirely by accident), letting people marinate in its mysteries before anyone unlocked the final cutscene revealing that P.T. was teasing his Silent Hills. At one point, you will be required to look for a puzzle piece in the game’s brightness settings menu. At another, you will have to speak a character’s name aloud into the controller’s microphone—it’s still not confirmed what the correct name is, only that certain names beginning with J seem to work. All the while, you’re being stalked by the ghost Lisa, who can kill you at a moment’s notice with one of the most shocking jump scares in video game history.

Even if you know exactly what to do, the game’s atmosphere is oppressive. Lisa is everywhere: lurking in the shadows of the second-floor landing, watching you from a crack in the bathroom door, standing in an inhuman pose at the end of the hallway. The game is played from a first-person perspective, but in recent years data miners have discovered that Lisa is actually standing right behind the player for almost the entire game, present in the game’s space even when the player cannot see her. In this way, P.T. has a capacity to frighten that extends even beyond the experience of playing it. Its very code seems to be haunted.

Kojima and del Toro went on to claim that P.T. was not narratively related to Silent Hills (except, presumably, for its unnamed player character portrayed by Norman Reedus) but was only intended to demonstrate the style of horror game they wanted to create. This makes it easier to analyze P.T. as a standalone work, yet there’s still a paradox here. This game technically doesn’t even have a name, any more than a trailer for a movie has one. Trailers can be appreciated for the artistry of their editing, but they are almost never considered works unto themselves. Even game demos, where players can play small portions ahead of their full release, are rarely seen as games in their own right. But because the game P.T. teased was never made, much less released, the only thing available to consider is P.T. itself. P.T. is a suggestion of a larger work, the ghost of something that never lived. Yet as Lisa shows us, even a ghost can feel tangible enough to touch.

For reasons which are still opaque, development on Silent Hills was canceled only a few months after P.T.’s release, and P.T. itself was pulled from digital storefronts. Konami went so far as to make the game impossible to redownload even for people who had previously played it. Due to the complexity of emulating PS4 games, P.T. remains completely inaccessible except to those who kept it on their hard drives. PS4s containing P.T. routinely sell for hundreds of dollars online, priceless artifacts of video game history.

One of the most compelling things about P.T. is the degree to which it departed from the hallmarks of a Kojima work. The man had spent the large majority of his career working on Metal Gear, and the notion of “a Kojima game” connoted “third-person POV stealth action.” P.T. is a first-person horror game; there is no hiding and no fighting. Where the Metal Gear games made grand yet abstract statements about global politics and society at large, P.T. told a more eccentric and specific story about misogyny, domesticity, guilt, and violence. With P.T., Kojima said things—mechanically and narratively—that Metal Gear did not provide the creative space to say. But if he really had outgrown his signature franchise, why would he go back?

*****

It’s not clear exactly what happened behind the scenes to cause Kojima’s relationship with Konami to disintegrate. What is clear, though, is that things got ugly. Konami took Kojima’s name off Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain’s box art. Stories began to emerge that Kojima was kept isolated from his team during the game’s later stages of development, forced to work alone on a separate floor. Konami banned Kojima from making public appearances to promote the game, going so far as to prevent him from attending the 2015 Game Awards despite The Phantom Pain earning multiple nominations. Game Awards creator and host (and friend of Kojima) Geoff Keighley told the crowd exactly why Kojima was not present, prompting deafening jeers.

Despite it all, The Phantom Pain was released. It departed from the previous Metal Gear Solid games in almost every way. Gone was the linear exploration of closed-off areas. The Phantom Pain featured two open-world maps, one in Afghanistan and one in Africa, dotted with enemy encampments. The game was structured around a series of isolated missions. The slow and deliberate movement of the earlier games evolved into something fast and fluid—the Snake of The Phantom Pain moved like a mountain lion, slinky and powerful. Consequently, the sites of infiltration in The Phantom Pain feel less like video game levels and more like real places, to be explored with authentic human movement rather than game mechanics. Kojima has had a long-standing interest in expressing forms of realism through abstract mechanics. The camouflage system in Snake Eater, which has the player use a menu to swap Snake’s uniform to colors that blend in with his environment, is a good example; patently absurd in one sense (how does he carry around all these different-colored outfits?), yet it reflects a tactile way of interacting with a virtual world. With The Phantom Pain, Kojima wanted things to feel real.

Previous Metal Gear games take on the form of action movies. The Phantom Pain feels like a job. The missions which the game is structured around are largely composed of wetworkcontracts for various organizations. Despite operating in Afghanistan at the height of the Cold War, the protagonist forces—named Diamond Dogs here—have no real political agenda. They take on jobs working against the Soviets for the American military as well as Mujahideen fighters, but when the action moves to Africa they pick up work for the socialist People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola. Mission briefings will sometimes detail convoluted financial or political connections, but often it seems like Big Boss is just interested in money and resources. These missions are impersonal to the extreme, an impression furthered by the relative silence of Big Boss himself, who is no longer player by series regular David Hayter. You might as well not be playing a Metal Gear game at all. Perhaps Kojima, who seemed to have grown weary of the series, wanted exactly that.

The game’s big reveal ends up feeling a little anticlimactic, largely because it wasn’t originally intended to be the climax.The Phantom Pain is split into two acts. One is primarily set in Afghanistan, the second in the Angola-Zaire border. The second act ends on a series of cliffhangers: a group of former child soldiers steal a Metal Gear and fly off to parts unknown; ally sniper Quiet is apparently killed protecting Snake; second-in-command Miller defects after realizing he has been working for a decoy. A third act was planned and partially completed, to be set on an island where the child soldiers had taken up residence. The breakdown between Kojima and Konami meant that the game was rushed out the door, and this portion was never finished. The Phantom Pain just sort of stops partway through its narrative, hastily papering over its unfinished scaffolding with a ridiculous twist. Unlike previous entries, which all reach bombastic climaxes, the last Metal Gear Solid game trails off into ellipsis.

When Kojima emerged from exile at in 2016, six months after his infamous Game Awards ban, he announced the formation of his own independent studio Kojima Productions (which he’d put together with his former Konami staff during the back half of the previous year), and even more shockingly shared a trailer for their first game, already in development. It was full of dark and abstract imagery: beaches of black oil and dead whales, a man (played by Reedus) with a necklace of USB sticks, a crying baby who vanishes and heralds five ghostly figures floating over the ocean. It couldn’t be further from the Metal Gear aesthetic. For anyone wondering if Kojima’s work as an independent artist would attempt to reengage with incomplete works like P.T. and MGSV, Death Stranding’s announcement seemed to make crystal-clear that he was moving on.

Kojima’s final games with Konami can be—and have been—appreciated on their own terms. They are undeniably compromised and their auteur’s complete vision will never be experienced. P.T., despite Konami’s attempts to bury it, was an indescribably massive influence on horror games in the years following its deletion, with indie games like Layers of Fear and franchise titles like Resident Evil 7 taking open inspiration from its hyperreal first-person exploration. The Phantom Pain, meanwhile, will always be an awkward part of the Metal Gear story, a game which tried to fill in a gap in the timeline but ended up leaving a more conspicuous one. Yet without those unfulfilled possibilities, we would not have the Kojima who, unburdened by franchise expectations, created works as original as Death Stranding and its sequel. Silent Hills and the third act of The Phantom Pain will always be among the great what-ifs of video game history, but at least their loss gave birth to something wonderful.