Setting Out

Cole Kronman on Metal Gear and Snatcher

In 1986, when Hideo Kojima first applied for a job at Konami—the company he would work at for 29 years, and where he’d helm several of the most acclaimed video games of all time—it wasn’t because of any particular affinity he held for their games. It was because they were the only game developer listed on the Japanese stock exchange. This is a quintessential Kojima anecdote. Was this a cynical bid for prestige, a desire to work with a reputable corporate entity and put his name on a well-respected, widely distributed product? Or does it suggest a genuine interest in making idiosyncratic art under the aegis of a successful company that’s willing to take risks? Whatever the reason, it seems indicative of an ongoing impulse to deflect any claim that video games are unserious.

Kojima originally didn’t intend to make games at all. The trajectory of his life was shaped almost entirely by his cinephilia. He grew up obsessively watching movies and dreamed of becoming a filmmaker, and in college, he tried his hand at writing novels, hoping to parlay any success into a directing career. Video games were another means to the same end. His cinematic aspirations would become the defining trademark of his games, and have served as the springboard for countless discussions about whether or not those games–and games in general–qualify as art.

And for all his critical and commercial success, few figures in video games are as polarizing. Hideo Kojima’s work is brilliant, stupid, invigorating, exhausting, and baffling. Fans will tell you he makes thought-provoking, politically trenchant art that bridges gaps between games, cinema, and literature, while detractors will tell you he’s a midwit narcissist who can’t stop huffing his own snake oil. What gets lost in either extreme is an assessment of Kojima’s motivation, which stems not from sheer bombastic provocation but from a genuine artistic investment in what video games can do and mean. The results, as they may with any maverick artist splashing around in relatively uncharted waters, vary.

****

Much of Kojima’s auteur status can no doubt be attributed to the fact that his games are about anything at all. As low as this bar is, it tracks with the evolutionary timeline of the medium, which largely wasn’t seen as a viable outlet for involved narrative storytelling until over a decade after its inception. Even then, narrative video games tackling adult subject matter were exceedingly rare. It was in this burgeoning landscape that Kojima carved out his niche: his games evoked real-world locations, time periods, and political concerns, tweaked just enough to suggest speculative fiction rather than outright fantasy.

Arguably more significant, though, was how those stories were presented. From the jump, Kojima approached narrative and gameplay as complementary elements of interactive art, experimenting with ways in which they could be braided together to communicate ideas that wouldn’t be possible in any other medium. The result is a conscious (and at times conspicuous) situating of the player as a key participant in the work.

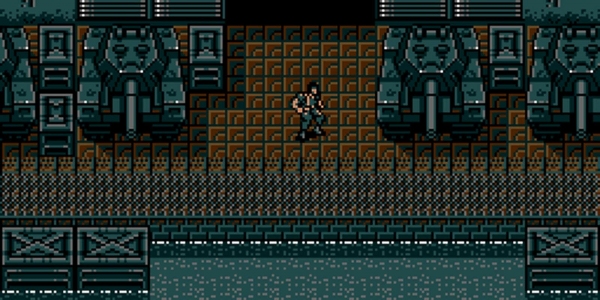

Kojima’s first game, Metal Gear—released on July 13th, 1987, for the MSX2 home computer—was defined by constraint. The MSX2 was not powerful enough to achieve parity with its home console and arcade contemporaries, which severely limited the development team’s options for what an action-heavy military shooter could look like. So Kojima elected to turn the game on its head, rejiggering its design to actively discourage combat. Stealth, as a game genre, was still nascent, and this was the moment it crystallized into something clearly identifiable.

In Metal Gear, players take control of a special forces operative codenamed Solid Snake, who is tasked with infiltrating the headquarters of an independent mercenary state and obtaining information about the top-secret munitions development taking place there. Even with the game’s light script—easily the most straightforward thing Kojima has ever written—its stealth gameplay has thematic resonance. By video game protagonist standards, Snake is weak. Approaching enemies head-on with guns blazing, as one might in a traditional shoot-em-up (an already popular genre in the mid-eighties), will invariably end with them swarming and overwhelming you. The only way to defeat them is to outsmart them, carefully avoiding detection and picking them off one-by-one.

Ironically, Metal Gear’s narrative hinges on Snake being one of the most capable soldiers on Earth: the game’s final moments reveal that he was sent into the base under false pretenses, so that he could be captured and later leak misleading information. The plan backfires, because Snake is ultimately too clever and too strong. This framework—wherein the player is made to feel weak, despite constantly performing superhuman feats of martial prowess—is our first glimpse at Kojima’s approach to design. The power fantasy is suggested and then kept just out of reach—a narrative carrot dangling from a mechanical stick.

Such tensions are Kojima’s bread and butter. While not necessarily distrustful of games, he’s certainly wary, because he understands intuitively what stories they best lend themselves to. Playing Metal Gear and its sequels is to see the anatomy of the medium laid bare: even with Kojima’s emphasis on player fragility, he can’t avoid the fact that there is nobody stronger than a video game protagonist, and no character better suited to the role than a soldier. Finishing a video game necessitates conquering it; conquering it means following, and issuing, orders.

Though Metal Gear’s story is relatively sparse, we can see Kojima’s geopolitical interests percolating in the margins, setting a thematic template that his later work would expand and complicate. The enemy headquarters are located in South Africa, which, at the time of the game’s release, was still gripped by apartheid, and had already seen the rise and fall of several state-aligned paramilitary and mercenary groups. There’s the titular Metal Gear itself, a bipedal, all-terrain “walking tank” capable of launching a nuclear warhead from anywhere in the world. And destroying it necessitates disobeying the orders of your dictatorial superior and fighting on your own terms.Though the political intrigue in Metal Gear is largely more suggestive than conclusive, your commanding officer’s betrayal–and the resultant straining of the player-game relationship–gestures toward the same distaste for blind patriotism that would eventually form the ideological bedrock of the Metal Gear series.

****

Kojima’s Snatcher would arrive barely a year later. Released on November 26, 1988 for the PC-88, Snatcher is a radical departure from the tactics-focused Metal Gear, instead taking the form of a graphic adventure game. Players progress through various screens—usually featuring detailed pixel-art drawings of building interiors—by selecting dialogue options, examining objects, and piecing together clues from a menu. It was a burgeoning genre at the time, with a number of standout titles (most pertinent here would be Yuji Horii’s The Portopia Serial Murder Case), though Snatcher was distinguished by its openly, at times brazenly referential bent, built almost entirely around evocations–and invocations–of cinema.

Kojima isn’t shy about his influences, and Snatcher marks his first time experimenting with a form that could be described, on a very basic level, as an interactive movie. Graphic adventures are not about testing your reflexes; they’re about participating in a story. Snatcher is one part Terminator, one part Blade Runner, and one part Invasion of the Body Snatchers, with a side order of Akira. It begins with amnesiac protagonist Gillian Seed suiting up for his first day on the job as a “Junker”—a state agent in charge of hunting down and neutralizing deadly humanoid robots known as “Snatchers.” Snatchers, as an opening cutscene explains, have recently begun menacing the island metropolis of Neo Kobe City, killing their victims and adopting their identities in daily life.

Snatcher announces Kojima’s penchant for eye-popping maximalism. Its world is shockingly elaborate, with dozens of optional interactions and scenarios, as well as an in-game searchable database through which players can learn about everything from Neo-Kobe’s ethnic demographics to its local cuisine. It simulates futuristic forensic processes, both with and without player input. Even in the original PC-88 release (I played the 1995 Sega CD version, the only one with an official English translation), lead artist Tomiharu Kinoshita’s visuals are extraordinary, evoking a sprawling, grimy cyberpunk metropolis with limited animation and color. Neon lights glide over surfaces, computers run scans, synthetic skin melts off the Snatchers’ metal faces.

From the beginning of the game’s development, Kojima’s driving philosophy was to make it feel like a film. His success is debatable—Snatcher doesn’t feel like a film so much as a collection of references to films, landing somewhere between homage and plagiarism. Kojima has an occasional tendency to conflate artistry with ham-fisted allusions to other, greater works of art. Whether or not Snatcher is a thoughtful piece of cyberpunk fiction doesn’t matter as much as its engagement in the legacies of cyberpunk fiction, and that it allows for active participation in them.

Kojima’s design sensibilities have always been far more coherent than his storytelling. His ability to impart meaning through play is what makes his work so compelling, not his mastery of the written word. In Snatcher, which couldn’t function without words, his worst impulses are put into sharp relief: its narrative is inconsistent, puerile, and jammed with clichés. If it were a movie, it would be forgotten.

But Snatcher is not a movie. It’s a video game. And it’s a great video game, because its genre trappings only serve to deepen the player’s involvement. We play detective not only to solve problems but also to interact with and observe a complex, mutable space. There’s the usual questioning of suspects and searching for evidence; there are also interludes where you’re given the opportunity to call your wife or grab a slice of pizza, or just wait around a bustling city square until something happens. Snatcher gamifies both impersonal detective work and intimate social relationships in the context of a story about the fraught relationship (and growing indistinguishability) between man and machine. This prompts us to broaden our own understanding of how technology can interface with human emotion.

During Snatcher’s development, Kojima (unsuccessfully) advocated for its floppy disk to be coated with a special chemical that, when heated inside of the disk drive, would smell like blood. Supposedly, the intention was to immerse players in “the smell of the crime scene.” Of course, this is a profoundly stupid idea, a cheap parlor trick with downsides far outweighing its initial shock value. Yet at the same time, it’s clear that Kojima was thinking seriously about just how corporeal technology can (and should) be, and where the boundaries of interactive fiction lie. Thirty-five years later, he’s still searching for them.

Across all of Kojima’s games, melodrama, political commentary, and pulpy science fiction compete for his—and our—attention. He is as enchanted by cool giant gun robots as he is terrified of the fact that such an invention, were it to exist, would forever alter global power differentials and push us all further toward mutually assured destruction. He recognizes the ways in which imperial powers corrupt and dehumanize their soldiers yet can’t always square this with his fundamental reverence for the soldiers themselves.

These contradictions, intentional or otherwise, seem of a piece with an ethos fueled by inquiry. In Metal Gear, we see the early vision of someone already experimenting with narrativized, politicized play, and sowing the seeds for ideas that video game technology, in some ways, is still catching up with. In Snatcher, we see that same play begin to chafe against a more slipshod (but no less earnest) interpretation of “cinematic” storytelling. The questions raised in these two games still cast a long shadow over the entire medium, and Kojima’s constant push for reinvention in the years since has made it clear that he hasn’t found the answers. Better, then, for him to keep asking.