In this weekly column, one writer sends another a new piece of writing about a film they have been watching and pondering over, in the hopes that this will prompt a connection—emotional, thematic, historical, or analytical—to a different film the other has been watching or is inspired to rewatch. This ongoing column is in the spirit of many past Reverse Shot symposiums, in which writers found connections between seemingly disparate cinematic works, and it will also help us maintain personal connection among our writers and our readers.

The World, the Flesh, and the Devil

While trying to charm the woman with whom I was on a date during a recent, risky beverage outing in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, I told a passing stranger my theory that those of us faring decently in this moment are the ones who have already led many lives. For our perpetually busy souls, this is all old hat. (Though I was not attempting profundity, this unknown fellow whipped out his phone to jot my words down in a note app.) My mind keeps returning to this idea that our actions during this trying moment—be they complacent, cowardly, bold, or heedless like my own—are deeply informed by our prior experiences. This might be a year with no true historical precedent in which to seek comfort, but it certainly has a way of goading personal reflection on years past and the individual struggles that have, bafflingly, set me up to thrive like a fattened subway rat.

Because it is summer, because this is New York, and because this is a pandemic, I’ve been mired in the predictable classics. Laura (1944). Night of the Living Dead (1968). Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Recently, @cinementalist lovingly Tweeted that another unsettling summertime opus, Rear Window (1954), has taken on a new weight with the proliferation of work video conferences. This initiated my return foray into Hitchcock. But the artwork with which I’ve fallen into an intense courtship during this uneasy summer is Ranald MacDougall’s postapocalyptic The World, the Flesh, and the Devil (1959)—its title derived from the fire and brimstone antithesis of the Holy Trinity named in Ephesians. Here, we enter a world where the city is gutted by crisis and an unlikely trio of characters is left to pick up the pieces, with arms quite literally interlinked.

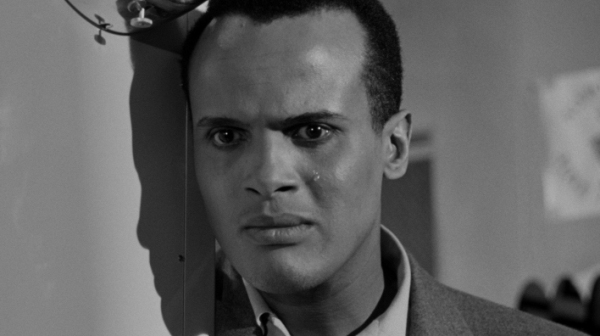

We first find Harry Belafonte’s Ralph Burton, a blue-collar maestro of metropolitan infrastructure, where the rats are. He is working underground while radioactive disaster and mass exodus plagues Manhattan. Lasting nearly ten minutes, it is a hell of an opener, one in which Belafonte’s every skill is tapped. He is his happy, physical self. Once a sonic boom occurs and Burton loses electricity and phone service, the Calypso vocalist begins to sing an anthem to the working man. Finding himself alone in the dark for days on end, Burton begins to have delirious conversations with himself. As a Genesis-like flood befalls him and precipitates his re-immersion, Belafonte becomes the action hero he’d be known for in Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), while the heartthrob archetype he effortlessly settled into five years prior in Carmen Jones will later be on full display when he encounters Sarah Crandall, a white survivor of the disaster played by Inger Stevens.

In the meantime, Burton is alone in a storied civilization without civilians. He develops rituals that help him stay sane and adopts two storefront mannequins to keep him company. Good meals, art, and companionship take on heightened, precious meaning—not unlike today. One gets the sense that Burton has, either by virtue of being Black, working class, or simply marching to the beat of his own drum, already lived a great many lives. Once his plastic friends are replaced by Sarah and the brooding, romantically competitive Benson Thacker (Mel Ferrer), Burton begins to navigate a new set of challenges that are extremely relatable on any day but more so in the wake of our own ongoing dystopia.

Here are the questions that The World, the Flesh, and the Devil is affording me answers to right now: How do we find ways to cling to the tenderest rituals of the civilized to maintain sanity in crisis? How do we answer the necessary call of play, flirtation, and love during hard times? How do we find ways to resist discarding others when others become a finite, invaluable resource? What are the intricate shapes that nonmonogamy can take? Yes, this is underscored even during a filmic era marked by the endless application of morality codes.

Romance holds a vital place in any ongoing movement; I am recalling a poster I once saw online of two Civil Rights Era lovers resting in one another’s embrace with a caption akin to “Be tender with one another so you can be powerful together.” Though dating in the present resembles a horrid fashion reality TV show where one must craft a gorgeous fascinator from a scrap of moth-riddled felt and a single pigeon feather, prior experiences have reassured me that I will be more than adept at plodding onward with grace: an act that the late poet Wisława Szymborska referred to as “giving birth among the ruins.”

In lieu of the extravagant New York City rendezvous I desire, for which this moment has no facilities, my many lives will guide me. The cinemas, department stores, and museums may be romantic realms of the past in both The World, the Flesh, and the Devil and the dystopian present, but there is pleasure to be found in long-forgotten films, in humble spaces still in operation, and the apartments we now have no choice but to nourish into domestic sanctuaries for work and play. As Crandell tells Burton in this wonderful film, “Women enjoy parlor games.” —Sarah Fonseca

Wildlife

Displacement has been on my mind. The economic ramifications of this pandemic are never more visible than during rent deadlines, with our government seemingly shrugging off the concept of a rent freeze. In my suburb, homes are being put on the market practically daily, and when I have gone out on walks and passed buildings, I’ve noticed several items—bed frames, coffee tables, lamps—on sidewalks, likely the belongings of evicted tenants. Occasionally I would inspect the conditions of these items but have never taken new ownership of them. They still had the aura of trauma around them, coming at a high emotional cost wrought by loss.

I had just moved into my house a month before the pandemic hit the U.S. The person who owned the house before me had seemingly lost it abruptly. There were unfinished projects all over, amateur attempts at house painting and carpentry. I bought the property with the intent of renovating. Major parts did get renovated, but due to these unforeseen events it’s still unfinished. I remain fascinated by a persistent, out-of-reach tear in the kitchen’s floral wallpaper. What was the story there? I saw a similar image in Paul Dano’s Wildlife, which I have watched and re-watched several times over this quarantine. It is a film about the dissolution of a marriage as seen through a teenager’s eyes, but it’s also about the instability of a physical place over a finite period of time. A house is not a home. As in The World, the Flesh, and the Devil, it’s a film aboutoutsiders dealing with a “new normal” that informs how they have lived and how they now want to live.

It is 1960, and the Brinson family has moved to Great Falls, Montana, from the Pacific Northwest. Early on, young Joe Brinson (Ed Oxenbould) sits with his school classmates during a presentation on fire safety from a Park Ranger. Joe jots notes while his fellow pupils, far more conditioned in hearing about the inevitability of the region’s seasonal fires, do not. It is their ritual, something Montanans all accept will always happen, something to be contained until the first snowfall. But Joe, not a Montanan, is unfamiliar with the inherent vice that comes with living in this vast landscape. It becomes clear that the looming natural disaster Joe should be tracking is not the environs that surround him but what is happening between his parents.

Joe’s parents, Jerry (Jake Gyllenhaal) and Jeanette (Carey Mulligan), married and had Joe young. Both of them love their son, but they each begin to crack and bend toward impulses that have them living largely separate lives: Jerry seeks to find a purpose by fighting fires after losing his other seasonal job at a country club, and Jeanette carries on an affair with wealthy salesman Mr. Miller (Bill Camp). Joe is put into the role of a latchkey kid and gets a job as a photographer’s apprentice. He has a bedroom, and yet he is constantly sleeping on the living room couch. There are no comforts in a place you barely know, except maybe where you can watch TV and feel less alone.

Cinematographer Diego Garcia (who also shot Cemetery of Splendour) recreates a William Eggleston-esque Americana, while the production design and art direction of Akin McKenzie and Miles Michael generate textures of Western kitsch and buildings that look alive and well preserved. Particularly striking are the rows of suburban brick ranch houses, like the Brinson home, which were made at the peak of the suburban postwar boom in the 1950s. Those houses stand today, some still boasting cable roof antennas, one-car garages, and outdoor laundry racks. It is clear that the Brinsons do not have much money, and that this second-hand ranch came cheap. This is perfectly expressed in that kitchen wallpaper; torn, worn out, and stained around the light switch.

This spot of wallpaper is such a telling detail of production design, a remnant of whoever previously inhabited this space. The fact that there are almost no personal touches from any member of this current, troubled household is indicative of how tenuous the Brinsons’ relationship is to this space, as is their lack of urgency to renovate and fix seemingly simple things like wallpaper. Such textural details anticipate the escalation of events that will further displace these three people and drive a permanent wedge between an already unhappy married couple. Jerry ultimately leans into his gregariousness and becomes a natural salesman, achieving professional stability. Jeanette finds the most clarity of the situation, ultimately leaving Montana to build her own life independent from domesticity and motherhood. Joe, on the other hand, may have to wait until adulthood to truly have a home of his own.

It would be reductive to label Wildlife as just another film about the failure of the nuclear family. The characters often appear estranged in their own spaces, in search of control, comfort, and stability. Is there any sentimental connection they must maintain to these spaces, or can they leave it all behind? In my privilege of still having some ownership over my space, I think about those with no such relationship. This could be due to the pandemic or simply because one’s sense of security—about home or the well being of loved ones—fades. Wildlife captures the brutal truth of the latter feeling with a blunt lucidity. —Caden Mark Gardner