In this weekly column, one writer sends another a new piece of writing about a film they have been watching and pondering over, in the hopes that this will prompt a connection—emotional, thematic, historical, or analytical—to a different film the other has been watching or is inspired to rewatch. This ongoing column is in the spirit of many past Reverse Shot symposiums, in which writers found connections between seemingly disparate cinematic works, and it will also help us maintain personal connection among our writers and our readers.

The Nun

“A world complete without me which is present to me is the world of my immortality. This is an importance of film—and a danger...So there is reason for me to want the camera to deny the coherence of the world, its coherence as past: to deny that the world is complete without me. But there is equal reason to want it affirmed that the world is coherent without me. That is essential to what I want of immortality: nature’s survival of me. It will mean that the present judgment upon me is not yet the last.” —Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed

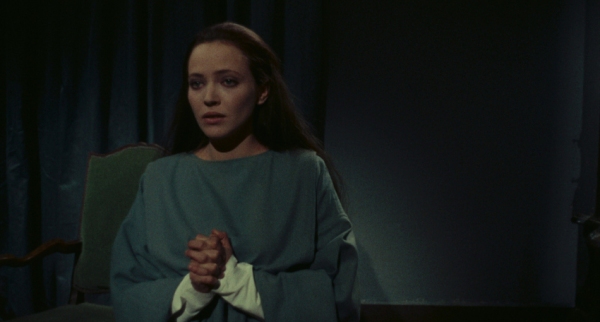

Jacques Rivette’s The Nun appears to take the psychological life of one woman—an 18th-century nun named Suzanne (Anna Karina)—as its primary subject, but the film’s concern proves to be even more intellectually expansive: you could say Rivette is interested in nothing less than the ruptures and lines of flight that define any transformation of human tradition and thought. The 1966 film is divided into two halves. In the first, Suzanne is forced by her mother to take her vows, subjected to all manner of torment by her Mother Superior, and makes numerous attempts to legally free herself from this religious life. In the second, she is relocated to another convent, which is diametrically opposed to the previous, and must confront the realities of this new place. The difference is considerable: it’s as though Suzanne, who radically contested the asceticism of 18th-century convent life, had been airlifted to a world governed by the ideals of female sexuality and liberation of the 1960s. She struggles to accept this as freedom just as surely as we struggle to understand why she can’t.

Today, the revelation of Rivette’s film has very little to do with the novelty of its structuring idea. After all, one sees these conflicts all the time in science fiction. I recently watched World on a Wire (1973), Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s TV miniseries about the creation of a simulated world. At the end of the first part of the film, our scientist hero learns that he is living in a reality housed entirely within a computer. In this moment, his plight becomes not all that different from Suzanne’s: their individual worlds do not contain the whole of the world, their knowledge is not absolute, their demise will be predicated on their disowning of this realization. We can call the tragic flaw of both characters, their inability to see their circumstances in any other way, their failure to acknowledge. Thinking they have confronted something absolute, deducing that they cannot live in a universe that can’t be mastered, they fall headlong towards oblivion. While World on a Wire suggests this encounter is spectacular, the rare fate of an enlightened few, The Nun comes closer to the truth of the matter: at a certain point, don’t we all wrestle with the contingent nature of what we previously considered necessary?

A similar tragic flaw leads many philosophers to think they can step outside of themselves and decipher the scrambled prose of the world (this, too, is its own failure to acknowledge). Amidst tremendous personal and global upheaval, I have nonetheless found much more solace in reading philosophy than I have in viewing films. And there’s been something rather therapeutic about it—not because philosophy has any special claim on knowledge, or because it is somehow more fundamental than any other discipline, but because it’s capable of doing the exact opposite of what its reputation for self-aggrandizement suggests: it can return us to the everyday; it can bring words back home, so to speak, to their original use; and in so doing, it can dissipate what we once thought were insurmountable problems. These past few months of relative isolation, the first line of the second preface of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason has never been far from mind: “Our reason has the peculiar fate that, with reference to one class of its knowledge, it is always troubled by questions which it cannot ignore because they are prescribed by the very nature of reason itself, and which it cannot answer because they transcend the powers of human reason.” This may sound like a curse; the trick, I have learned, is to see it as something of a blessing.

Being trapped in our bodies, at the specific moment in which we will live, without any access to a transcendent outside—this is only a problem if we make it one, if we fail to acknowledge the very circumstances through which we live, think, and love. Perhaps one goes to the cinema assuming that we can somehow overcome these basic “limitations” and defeat skepticism (of the external world, of other minds) once and for all. This is the danger Stanley Cavell identifies in the quotation at the top of the article, and it’s the one The Nun convincingly averts through its structural conceit.

When Karina’s religieuse moves into the second convent, she comes under the rule of Mme de Chelles, a caring, tolerant, and affectionate woman. It soon becomes clear that, while Mme de Chelles is unmistakably genuine, she also carries ulterior motives, or at least, a forbidden attraction, which Suzanne is unable to fully comprehend. Here, we might say, Suzanne has reached the limit of her world just as we become cognizant of the limits of our own reason and the finitude of our own lives. Our understanding of Suzanne can only go so far given our distance from the film’s time period, and contextualizing her behavior won’t help us truly understand it. If this is acknowledgment, we might equally point to its opposite, avoidance, which, in Suzanne’s case, might equally be called the avoidance of love. —Josh Cabrita

My Name Ain’t Suzie

This is one of the few Rivette films I haven’t seen before, and I’m half-glad that you’ve forced me to get around to it. I was raised atheist by someone who clung to the bitter Lutheran asceticism of her youth—a disposition that evokes color palettes of those in 18th-century convent life—which is part of the reason I’ve let this one sit for a while. Despite all the philosophy books I’ve bought over the years, I was overwhelmed by the stultifying nature of Suzanne’s experiences rather than the philosophical underpinnings you’ve laid out. Rather than view her motivations as opaque, I understood them on a profoundly emotional level, but also as refracted through the rest of Rivette’s oeuvre.

After the magnificent rebellion of the first scene—perhaps the closest Suzanne gets to the anarchy of Rivette’s later heroines Céline and Julie—she is moved from one cage to another by more powerful handlers, never through her own agency. In addition to being a victim of a patriarchal system that made her a financial burden rather than a person, she’s a 20-year-old who has been physically and psychologically abused, tortures that have compounded her fears of being a pariah and ground down her confidence to a nub. If her choices seem illegible or bad, it’s exactly because she’s only been given shitty propositions. (Still, I found myself wishing that she’d at least tried fooling around with Mme de Chelles.) For most of the people who have lived in it, the world has always been not our own. The pandemic has kicked out many groups who were formerly in it.

In addition to Rivette’s other films, I found myself thinking a lot about Angie Chen’s 1985 My Name Ain’t Suzie while watching this. A friend in Los Angeles asked me to program a double bill for a group of cinephiles out there, and I appeared via Zoom to introduce Chen’s film and Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention very late this past Saturday night/Sunday morning. I was thinking of movies that indirectly commented upon quarantine, specifically of things that focused on restriction of movement, uncertainty, and not entirely comfortable stasis. I had originally seen My Name Ain’t Suzie as part of Metrograph’s amazing Shaw Sisters series last August, and I’m still baffled as to why this unsparing, fascinating film hasn’t been shown many more times since.

Chen and cowriter Chan Koon-Chung imagined the film as a rebuke to The World of Suzie Wong, an orientalist tragi-fantasy from 1960 starring Nancy Kwan and William Holden. In order to truthfully express the lives of Hong Kong sex workers, Chen and Chan spent a lot of time with actual sex workers in Hong Kong’s Wan Chai district. Like Suzanne, Shui-mei (the fantastic Pat Ha, who made her debut in Patrick Tam’s Nomads) is also an “excess” daughter, but she goes directly to sex work rather than stopping off in a nunnery. The film avoids any male perspective—there are no scenes of the “bar girls” having sex with their clientele, nor is there any postcoital pillow talk. (The one main male character, played by Anthony Wong, is total basket case whose desperate search for daddy demystifies the sexiness of James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause character.)

Shui-mei undergoes hardships. To name a few: she gives herself an abortion in her bathtub, she is beaten up by gang members who are trying to take a cut of her business, and her lesbian protector is brutally mutilated—but we’re told by a friendly narrator that Shui-mei is only temporarily on the back foot at the end. She is a victim of the patriarchy, but Shui-mei has found a space for herself within it, and done better than she ever could have back in her fishing village. She runs her own brothel, yet she seems to be a kind madam, unlike the one who taught her the ropes—something that suggests evolution. Could the aristocratic Suzanne learn something from Shui-mei, who painfully brought herself up by her bootstraps and retained her sense of dignity? Each is a victim of her own surroundings, so all signs point to no.

The pandemic in this country has no end in sight, and while it’s sometimes necessary to escape into fantasy, I fear letting myself drift too far. I find myself thinking of the endless complications, drama, and glitz of My Name Ain’t Suzie, but never for too long.I agree with John Steinbeck’s assessment that Americans believe themselves to be temporarily embarrassed millionaires. I fear that we are also becoming a nation that believes ourselves to be temporarily embarrassed by COVID-19 and Donald Trump, and by doing so, we are a nun without vocation who dreams of scaling the convent walls without thinking of what’s on the other side. —Violet Lucca

Reverse Shot is a publication of Museum of the Moving Image. Join us at the Museum for our weekly virtual Reverse Shot Happy Hour, every Friday at 5:00 p.m.